The building Patrick Stewart designed on Seabird Island is more than 20 years old, but the architect still points to it as a favourite example of using place-based knowledge to inform indigenous design.

Built in the form of a single slope longhouse, the 16,000 square foot structure - on the reserve east of Agassiz - was a reaction to a school designed and funded by Indian Affairs in the late 1980s.

"The community wasn't involved," said Stewart, and as a result it wasn't used to its full potential. By contrast Stewart's design for the administrative and recreation centre - constructed at one third of the cost - considered the community's love of soccer in its gymnasium, used basket weaving patterns on the walls and inset stones shaped like a fireplace in the lobby. He recalled elders seated in a circle around the granite slabs.

"They treated as if it was an actual fire," he said, proof in its use that design can foster community if it addresses need.

It's this aesthetic and this consultative approach that are central to indigenous design - all elements Stewart will address at his lecture at the downtown Prince George Public Library Wednesday at 6 p.m.

"Being place-based means any culture is as important, is as equally able to influence the design as any other," said Stewart, but that hasn't been the Western approach to design. As an associate professor Laurentian University, he is pushing for an indigenous stream to expand those understandings.

Sometimes in presentations Stewart uses a slide and three letters to address that design challenge. It reads: "White is better."

"As First Nations people that's what we're always up against," said Stewart, who chairs the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada's Indigenous Task Force. "Each different nation has its own histories, its own language, its own culture that it has privileged over the years and has been its tradition. With the advent of colonization all that has been taken away or pushed aside."

"Respecting culture in Indigenous communities through design and construction is, I believe, important but largely ignored in places that have a history of multiple challenges," said RAIC president Allan Teramura said respecting culture through design and construction is "important but largely ignored."

"It's essential that Indigenous architects take the lead in this initiative - as this requires an exceptional level of cultural sensitivity, experience, and understanding," said Teramura in a statement for the task force's launch in June. "Having said that, there are non-Indigenous architects who have those qualities and have an important contribution to make."

Stewart, who is from the Nisga'a First Nation, was the first Aboriginal president of the Architectural Institute of B.C., a first for the province and for the country. He was also the first Aboriginal person in B.C. to own and operate an architectural firm.

Stewart said he is one of only 13 Indigenous registered architects in Canada and two in B.C, a solitary distinction he shares with Alfred Waugh. In 2011 the country had 15,255 architects, according to Statistics Canada.

The tiny fraction indigenous architects embody is not surprising to Stewart. Until 1951, Aboriginal people weren't permitted to go to university unless they enfranchised and gave up their status - an assimilative practice by the government that was also required of Indigenous veterans who chose to fight in the Second World War and of women who married non-Aboriginal men.

Many communities, he said, first pushed their youth toward certain professions - like lawyers, educators and the social services or health - as ways to regain control in their communities.

But design also has impact on self-determination.

"Environment affects you, it affects people," said Stewart, adding in his more than two decades in practice, he's noticed some common experiences in Indigenous aesthetic.

Many First Nations he's worked with have clear ideas about what they do - and don't - want to see in their communities. Much of the negative associations to buildings were in response to residential schools.

They didn't want white walls. They didn't want brick.

"They wanted colour," said Stewart, who has worked with more than 40 communities. "The monumentality, they didn't like that. They had reactions and there was some interest in some of their own cultural elements to be incorporated in the buildings, traditional form, which had been taken away."

He sees himself as a facilitator as much as a designer, and stresses local input before he pulls together a blueprint.

"The cultural vision needs to come from the community," he said, adding he'll say during consultations: "When I leave it's your legacy, it's not mine."

In his 2015 PhD thesis he wrote: "all of my projects use interpretations / abstractions of ancestral histories sacredness and / or environmental relationships as a medium to represent the concept of indigeneity in building design."

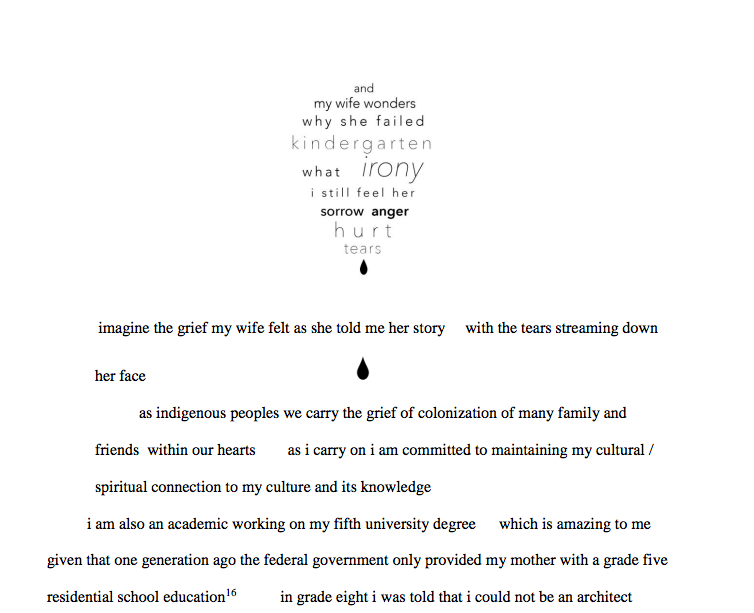

The 223-page document was rejection of English language conventions and appeared in lower-case letters, void of punctuation like a long run-on sentence or a poem. At the time, he didn't know if he would pass, even after many meetings explaining why he was flipping the form.

"I felt that writing a dissertation was the time to push the boundaries," Stewart explained, but he also wasn't interested in blindly following conventions.

During his defence a Tsimshian examiner was the first to speak.

"He said I could hear my grandfather speak in the longhouse," he said. "That set the tone for my oral. It was just amazing."

That experience strengthened his resolve. Stewart's had projects labelled "too exotic" or "too in your face." His approach could be considered experimental, but he's not interested in fitting in.

"There may be a time for subtleness at some point but to me there's so few of us and so few projects being designed and built that we can't be subtle."