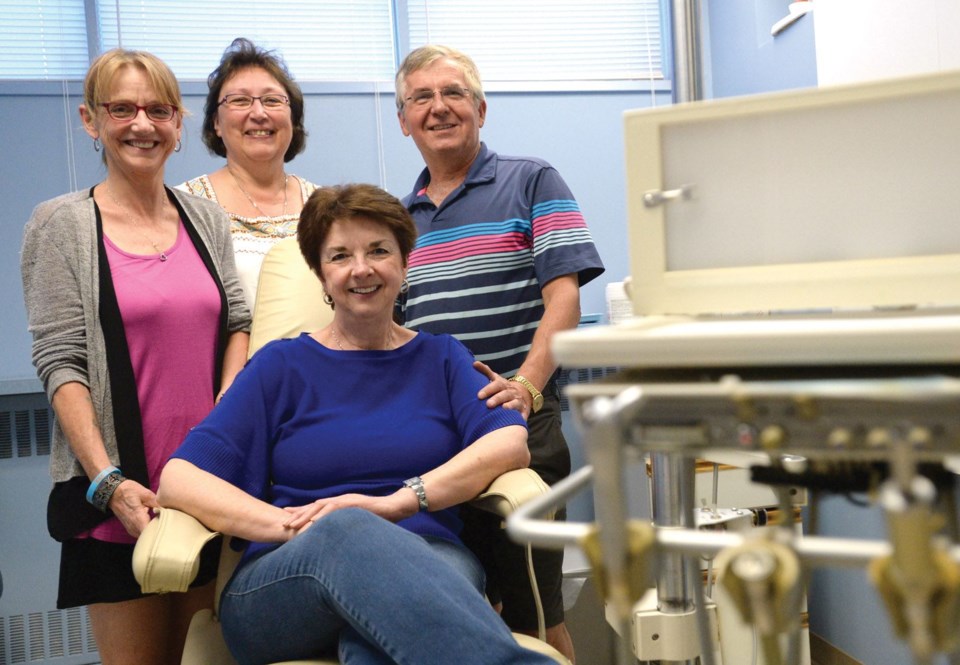

Tucked in the back of the Prince George Native Friendship Centre in a tiny room just big enough for a front desk, filing cabinet, small sink and two dentist chairs, Carole Whitmer and Dr. Richard Wilczek seem part of the furniture too.

"It's hard to believe that it's been 10 years," says Wilczek.

The two sat on the original committee that brought the Emergency Dental Outreach Clinic to Prince George in February 2006.

On the light-blue walls, a poster shows a blackened tooth, similar to the ones Wilczek, a dentist, has pulled at the free clinic since it started.

Most days the two chairs are empty, but twice a month volunteer dentists, dental assistants and hygienists help remove far-gone teeth that have been plaguing patients with pain. People come in with a variety of symptoms. Large holes in their teeth, black markings, pus on gums, facial swelling or complaining of a bad taste in their mouth.

It isn't the most glamourous of procedures, but having a problem tooth pulled makes all the difference for patients, Wilczek says.

"If we can improve how people feel about themselves, that's the first step in building self esteem. You feel better about yourself, you can move ahead with other challenges. If you don't feel great about yourself, it's hard to move on," he says.

A toothache is a constant source of pain and distraction, and if not treated by a dentist, it can get off-loaded onto the healthcare system.

"Usually what it means is it's a revolving door of meds," he says.

"Our highest number of referrals when we first started was from the ER," adds Whitmer, a founding faculty member of the College of New Caledonia's now-suspended dental hygiene program. "If you have a chronic infection, or chronic pain, that's going to compromise your overall health."

The free clinic operates on a first-come, first-served basis. Patients sit in a row of chairs that line the wall outside the small room. Volunteers have helped as many as 22 patients in one night. For those afraid of the sterile big office environment, it offers a feeling of community.

Since it started, the clinic has helped more than 2,400 patients.

"It's got a great reputation," says Gloria Gardner, before listing communities where patients have travelled from: Williams Lake, McBride, Prince Rupert, Dawson Creek, and more.

The next closest clinic is in Kamloops.

Gardner, who is often the first point of contact as the clinic's part-time coordinator, says many haven't dealt with dentist for years.

"We just try to comfort them and say the best thing that you did - the bravest thing you did - was come in through those doors tonight. And their shoulders just drop. There's a calm immediately. We take great care of our patients," Gardner says. "We really, really do."

Above her desk, a few cards are taped to the wall. She holds open one.

"Thank you very much for all you did for me, so I can smile again," says one.

Another man says all he can afford is a $10 donation, but the extraction means "I can now chew on that side of my mouth."

"Hurrah!"

That appreciation is common from patients, says Whitmer. When she first discovered the need for this kind of care, she was volunteer at St. Vincent de Paul and would ask the people what they did when their tooth ached.

"They said they'd pull it out or go to the hospital," she says. "A lot of people are afraid of big clinics, they don't have a vehicle to get there, they sometimes miss appointments."

So they designed the clinic with that in mind and, in an effort to get funding, Whitmer would call the deputy minister of health every day, pushing for a grant.

"She has been probably the biggest booster of this," says Wilczek of Whitmer, who won an award for her work with the clinic.

Eventually the money came from the Ministry of Employment and Income Assistance - a one-time $50,000 pot of money. The local rotary gave $10,000 for sterilization equipment, and Northern Health budgets $10,000 each year to support a coordinator at the clinic

That was all they needed to get started and on Valentine's Day in 2006, the clinic opened its doors.

"Instead of going home with my wife, I worked here," Wilzcek says with a laugh.

Everything else comes from volunteer work or donations from the community or the few dollars patients can afford. The clinic has a strong contingent of local dentists, between 15 and 17 Gardner estimates, who can be regularly called upon to help. That makes up a pretty good percentage of the about 40 dentists in the town, Wilczek says, especially when a third wouldn't be comfortable doing extractions in the first place.

The partnership with Native Friendship Centre's has been essential, Whitmer says, with free rent and utilities, accounting services and administrative support for a decade.

"Without their support we would have a hard time surviving," Wilczek added.

"It's really critical because of the needs of our clients," said Barb Ward-Burkitt, the centre's executive director, adding it serves about 50,000 clients. "The people that come here are experiencing poverty, they're often transient to this community so they haven't got a regular dentist.

"There is those things where they're pulling their own teeth. They're suffering so it's a part of a bigger picture in terms of holistic support."

The bulk of the clinic's clients are the working poor, those making just enough to live above the welfare line, who have little to spare for oral health.

Sometimes the clinic has restorative clinics where they offer fillings, but that's usually once or twice a year. A regular restorative approach is the ultimate goal, but a far-off one that requires more funding.

"The vision is we shouldn't exist. If the care was so well provided, we would not exist," Wilczek says.

"It's always been amazing to me why dentistry isn't a part of health care," Whitmer adds. "That's a whole other issue. Who decided to disconnect mouth from the rest of the body? There's links between periodontal disease and heart disease," she said, and low birth rate babies and more. "That's not likely to change."

For now, Whitmer says this model has worked.

"People appreciate that service is here."

The clinic, at 1600 - 3rd Avenue, operates on the second and fourth Tuesday of each month, and is on a-first-come-first serve basis.