As B.C. lags behind other provinces to produce homegrown physical therapists, northerners have been calling for more student spots as the region suffers from an acute shortage in care.

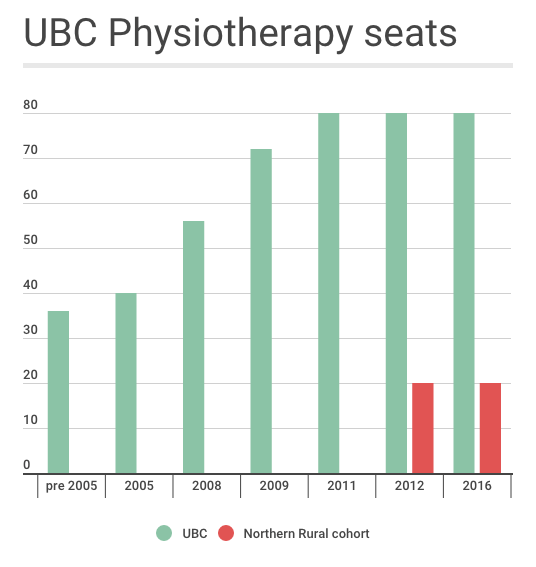

The 80 annual openings in the University of British Columbia's Masters of Physical Therapy Program are not enough to fill the need the province faces, let alone the north, which has three times fewer practicing physios compared to other areas of B.C.

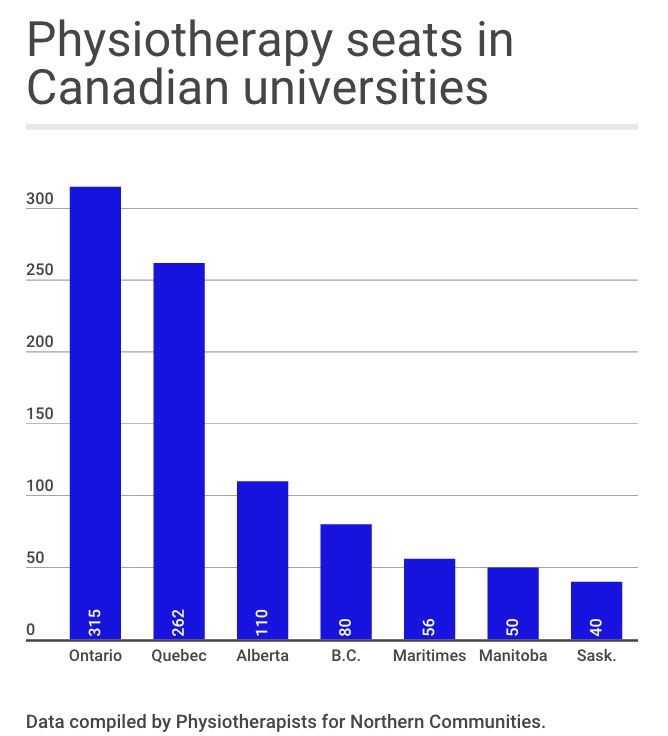

UBC's admission rate has sat at that number since 2011, when the province bumped funding from the 72 spaces it had offered since 2009. Ontario graduates about 315 students each year from five universities, Quebec 262 from four and the University of Alberta 110.

"B.C. relies more heavily on in-migration of physical therapists than any other Canadian province, with 62 per cent of practicing physiotherapists being educated outside of B.C.," said a Physiotherapists Association of B.C. presentation to government in 2014.

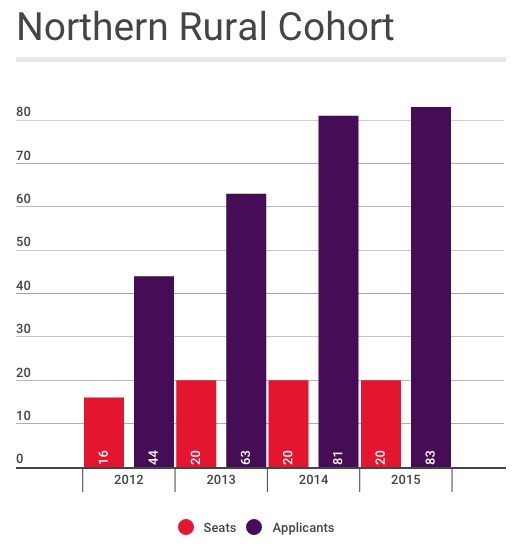

Since 2012, 20 of UBC's seats have been allocated to the Northern Rural Cohort, for students with an interest in practicing in remote communities. The desire seems to be there, too. The last two years UBC has received more than 80 applicants for the 20 cohort positions, up from 63 applications in 2013 and 44 in 2012.

Terry Fedorkiw has been one of the voices repeating the need for academic training that keeps students in Prince George. While the cohort does most of their placements out of urban centres, their coursework is in Vancouver.

Fedorkiw keeps a stack of papers with notes that reference meetings as far back as 2003 and last year she helped create Physiotherapists for Northern Communities (PNC) in an effort to ramp up their advocacy.

"We've been doing a lot of work... Our goal is to get physiotherapy services equal to the rest of the province," said Fedorkiw, who has practiced more than 40 years and keeps working because of the limited local services. "We could divide ourselves in 10 and not fill the gaps."

"I'm the face of physiotherapy now: senior," said Fedorkiw, 68.

As groups push for more seats, neither UBC nor the Ministry of Advanced Education could confirm if it would happen in the near future.

The northern rural cohort has seen "some very encouraging results," said William Miller, associate dean of health professions for UBC, in reference to early indication that as many as half return to rural communities.

"However, the NRC is still a work-in-progress, and we only have two years' worth of graduates so far - a total of 36 - to evaluate it. We have been having ongoing discussions with the Ministry of Advanced Education about the outcomes to date, and will continue to do so as we accumulate more data," Miller said by email. "Any decisions that might arise from those discussions would be made by the Ministry of Advanced Education."

Before the government committee, the Physiotherapy Association of B.C.(PABC) signalled some conversations had been happening.

"(UBC) can't get funding for more at the moment. We keep trying. But even UBC wants to place the extra 20 up here, because they see the need up here," said Hilary Crowley, a member of the PABC and PNC, told the finance committee.

"I think somebody has got a really, really tight hold on the finances in the province, because the need is identified and yet there are no more seats being offered," Crowley later said.

The ministry said it doesn't have any "formal" or "active" proposals to expand the physiotherapy program at UBC or UNBC, noting the latter is the "clinical education hub for northern and rural physical therapy training.

"The capacity to expand health-education programs is affected by the availability of clinical placements, physical space on academic and clinical campuses, qualified faculty, student demand and available funding," said the ministry's statement.

The northern cohort receives $645,000 as an annual operating fund, the ministry said.

Expanding the Northern Medical Program

As northerners like Fedorkiw push for more spots down south, their longterm dream is to mimic the Northern Medical Program's approach to physician training offered in Prince George through a partnership between UNBC and UBC, now a decade old.

A northern program means students can start to build a local network of support, said Robin Roots, coordinator of UBC's Northern and Rural Cohort.

"From the very beginning we've always wanted to have a fully distributed program," said Roots from a UNBC classroom in July as a video-feed from Vancouver played in the background. "Clinical placements are great and it's super that students have some time in rural communities but we know... the length of time there is directly proportional to the likelihood that they're going to practice there."

The case for the cohort typically comes back to recruitment to smaller communities, but there's also an immediate spin-off when it comes to better care, said Roots, because UBC funds programs across the north.

Three years ago, Prince Rupert opened a clinic that is fully staffed by UBC students, for example, in an effort to address a "huge shortage of services" and longstanding vacancies.

"You can point directly to the fact that we have more access to services," said Roots. "There aren't those jobs there and those positions otherwise.

"So the longer we keep our students here, the better."

Northern training is a common solution in Canada, where health care shortages are felt in rural communities across the country. The University of Alberta sets aside about 12 spots a year for students to study in Camrose. Southern Ontario universities partner with the Northern Ontario School of Medicine to set aside a number of seats for students who will take northern placements. Laurentian University in Sudbury used to train physiotherapists in the north. Its Northern Studies Stream, which accepted about 33 a year, closed this year in part because it was an expensive model.

"We know that it works," said Marion Briggs, the health sciences director at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine. "The preponderance of data shows that people from the north are more likely to practice in the north."

A 2015 survey of physiotherapists by the Canadian Physiotherapy Association found 45 per cent of rural physiotherapists said they made that choice because they grew up in a rural community.

Kate O'Connor, director of practice and policy at the Canadian Physiotherapy Association, praised Ontario's northern-focused training for broadening access to rural residents.

"It has a large number of indigenous health professionals that graduate. I see that as a really good opportunity to grow the number of health professionals that might stay in their communities or at least return."

But a program can be costly and some have suggested that clear connection means another approach could work, Briggs said.

"Rather than starting a new program... would it make more sense for all universities to have some kind of mechanism to have quotas for students from certain areas?" said Briggs, noting she isn't advocating the option, also "fraught with all kinds to problems."

In the meantime, Fedorkiw and others have been rallying for support. When PNC spoke to the standing committee of finance in September 2015 and the Physiotherapists Association of B.C addressed the health standing committee in July 2016, each recommended more seats at UBC.

In 2015, the Regional District of Fraser-Fort George, the Village of Valemount and the Union of B.C. Municipalities all signed resolutions calling for the creation of 20 additional seats.

This year, the Central Interior Native Health Society joined the chorus too.

Fedorkiw said she hopes the political will is finally there, praising local MLA Shirley Bond's support over the years and noting inclusion in the B.C. Liberals' Northern Economic Strategy

"Continue the growth of healthcare training in Northern B.C. by expanding the Northern Medical Program to areas such as physiotherapy," read the resolution, adopted in 2014.

"We have the support of everyone but we haven't got anyone to loosen the purse to fund," said Fedorkiw, adding PNC is trying to get a meeting with the Ministry of Advanced Education, which she's heard is the key body for the decision.

"We need commitment."

Click though the timeline below to view the growth of UBC's physiotherapy program.