School District 57 is calling on the province to prepare a poverty reduction plan in the wake of an annual report showing one in five B.C. children lives in a low-income family.

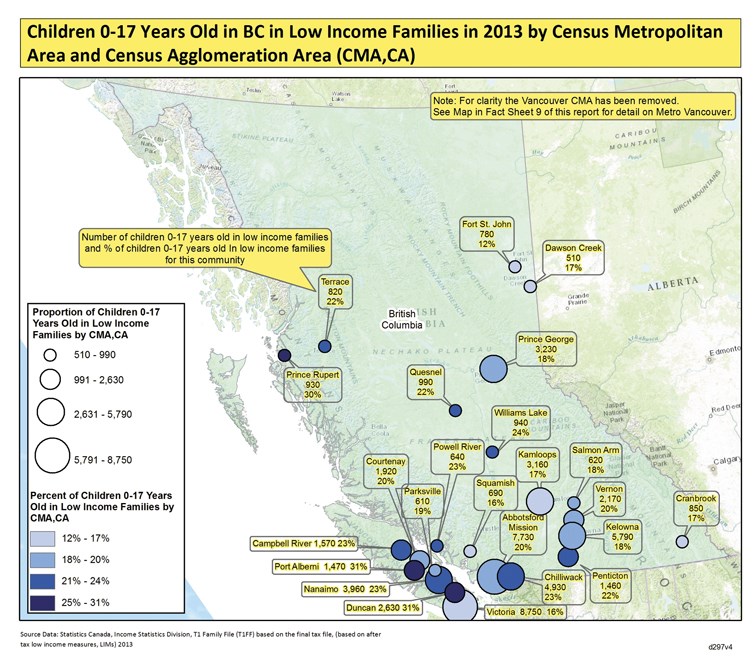

In Prince George, 18 per cent of youth under the age of 17 live in poverty, according to First Call: B.C. Child and Youth Advocacy Coalition’s report card released Tuesday.

For children under five, that jumps to 21 per cent. For single parent homes, the provincial numbers are worse, noted trustee Tim Bennett, with half living in poverty.

“Those numbers, personally, are just shocking and sickening maybe is a word that I don't usually use but that is how I felt this afternoon when I read the report,” said Bennett at Tuesday’s meeting as he tabled the motion.

Trustees voted to send a letter to Premier Christy Clark and Stephanie Cadieux, Children and Families Development Minister, “to allocate resources to develop and implement a provincial strategy for reducing child and family poverty in British Columbia.”

Bennett said Prince George’s schools see some of the the most vulnerable kids in the province.

“Our schools are providing so much additional support in improving conditions for learning that core education takes second priority,” Bennett said.

“If kids are coming to school maybe not getting a full night’s sleep, or are bouncing between babysitter to babysitter because parents are working two to three jobs, coming to school hungry - they’re not able to learn if they’re not coming to school in a condition to learn.”

Bennett criticized the province’s approach to a 2012 pilot project, which made Prince George one of seven communities tasked to create poverty-reduction strategy specific to the city.

Bennett was named to the committee, but only attended two meetings before Prince George backed out of the project. By October, the Union of B.C. Municipalities, which had partnered with Ministry of Children and Family Development, followed suit.

Betty Bekkering, a former trustee, was an original member of the Prince George pilot group, and remained on as a community representative after she lost her seat in the election last year.

She said Prince George chose not to participate, in part due to lack of support.

“We really need(ed) some help from the government to either expand this to other communities or help enlarge on our plan, but nothing came,” she said.

The October UBCM report noted the city’s departure and that the process had produced mixed results.

“Participants also struggled with the broader vision of the initiative and what it was trying to accomplish,” it said.

In the Ministry’s 2015 pilot project report, Cadieux said MCFD would keep its director of the Community Poverty Reduction Initiative.

“MCFD will continue to support the work of each participating communities. Family Consultants will remain in the community to continue to connect low-income families with services, and to work collaboratively with community partners and participate on the local poverty reduction planning committees.”

Bekkering said Tuesday’s poverty report revealed “what we already knew, although the statistics are getting higher.”

The numbers, taken from 2013 Statistics Canada data, show a five per cent rise from 1989, when poverty sat at 15.5 per cent.

“All we’re doing right now is enabling people to live within poverty. We’re not helping them out of poverty,” Bekkering said.

“There are so many kids going to school hungry and are living in poverty – and so many of our aboriginal students,” she said. “It’s the saddest thing, our teachers are keeping granola bars and things in their drawers to help kids get through the day.”

For Bennett, who also serves as executive director of Big Brothers Big Sisters, he’d like to see a province-wide plan, complete with more funding and more conversations with communities.

“I think the initial desire was that these pilots were going to help the province develop a poverty reduction plan and without the conversation happening, there’s not any work being done – from an outsider's perspective.”