This week in Prince George history, Oct. 2-8:

Oct. 4, 1918: The Citizen received news about an unusual military assignment for a former Prince George man.

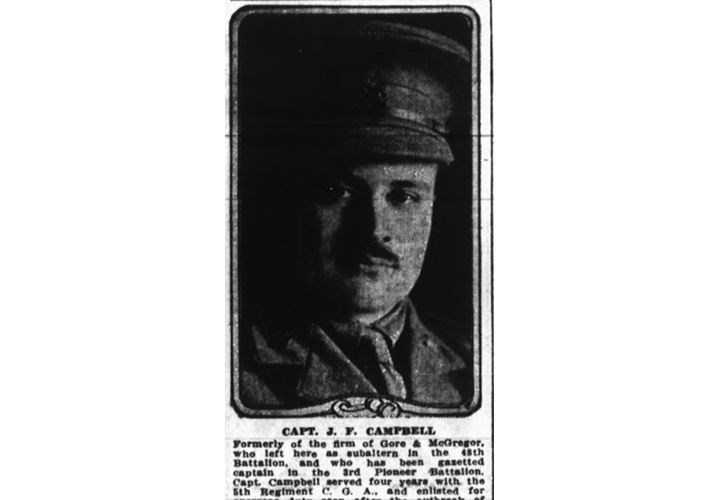

Major J.F. 'Doc' Campbell arrived in Victoria, "having been brought back to join the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force," The Citizen reported.

"For the past 18 months he has been commandant of the officers' engineering school at Bexhill (Bexhill-on-Sea, in Sussex, England)," the report said. "The previous 18 months he was in France. He won the Military Cross at Courcelette in 1916."

The history of the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force is an interesting, and little-known Canadian, military episode. But first, a little more about Major John Forin 'Doc' Campbell, courtesy of the archives of the Victoria Times Colonist, known in the early 20th century as The Daily Colonist:

Major John F. Campbell received the Military Cross for conspicuous gallantry in the field, The Daily Colonist reported on Jan. 3, 1917.

Campbell was the eldest son of the Rev. Dr. John Campbell living on Fort Street in Victoria. The senior Campbell was also the chaplain of the 50th Gordon Highlanders.

"Private advices received by his relatives state that Major Campbell was some time ago recommended for a decoration in recognition of his courage and resource at the fighting around Courcelette last fall. He was placed in charge of 300 men and given orders to establish a position wherefrom the British might direct their fire upon the enemy," The Daily Colonist reported. "Mayor Campbell constructed a road to the objective and, under heavy fire from the enemy, managed to clear the way for bringing up the guns. While a number of men were lost in the undertaking, it accomplished the object and the guns were able to drive back the Germans a considerable distance."

Campbell first enlisted in August 1914 as a regular soldier with the 50th Gordon Highlanders, before being commissioned as an officer and transferring to the 48th Battalion, which had become a pioneer unit upon arriving in England. Pioneer units were responsible for the construction and maintenance of earthworks, field fortifications, trenches and artillery positions - a critical role in the trench warfare of the First World War.

Prior to joining the Gordon Highlanders, Campbell had been a reservist with the 5th Regiment of the Canadian Garrison Artillery for four years.

"In civil life, Major Campbell was a land surveyor, being associated with the first of Gore & McGregor. While in the surveying business he spent some three years at Fort George," The Daily Colonist reported. "He was made a captain and major in rapid succession after reaching the scene of battle, and these promotions were fully deserved by the splendid service which he gave his battalion."

Campbell's three younger brothers, Walter, Douglas and Gordon, also served overseas. Two had returned, disabled by wounds, while the third remained on active duty, The Daily Colonist reported.

In a letter to his father, reprinted in The Daily Colonist on July 6, 1917, he described his role in one of the defining battles in Canadian history.

"For weeks before the attack on Vimy Ridge guns of all sizes, from 18-pounders to enormous 15-inch, were being placed in position. In order that these guns might not be located by the enemy and knocked out, they were not fired until the day of attack. For several weeks my company was employed on tunnels that ran under the German lines," Campbell wrote.

"These tunnels were, in some cases, started more than half a mile from the line, and were from 20 to 50 feet underground. They were extended out into 'no man's land,' where openings were made. We laid tracks in them to run up ammunition, and electric light was also installed. Before the attack troops were assembled in the tunnels, and thus large bodies of men were moved up to the line with very few casualties."

Massive craters, between 100 and 200 feet wide and up to 50 feet deep, had been blasted by the Germans to create barriers for attacking troops, he wrote.

"On the morning of (April 9, 1917) the most intense bombardment of the war started," Campbell wrote. "Thousands of guns, many of which had not fired until that morning, opened up -the bigger guns throwing a barrage in front of the advancing infantry and the heavies keeping down the German fire by strafing their gun positions."

Campbell's battalion was ordered into the trenches in the morning and stayed there in reserve until 3 p.m., when they were ordered to advance.

"The German barrage was a half-hearted affair, and consequently we had only a few casualties while passing through. Our greatest worry was machine gun from the left. But at 5 o'clock our guns silenced them. Our allotted job being finished, we started back in the darkness of night, in the face of a blinding snowstorm, being cheerful and in good spirits, satisfied with a good day's work," Campbell wrote. "From the top of Vimy Ridge the country stretches out for miles. Dozens of villages and cities are in view on the plain below. It is like viewing the promised land from Pisgah's top. Soon we hope to drive the obstinate Germans out of France."

While the Germans would eventually be driven out of France, Campbell wasn't there pursuing them. He was wounded by a bomb dropped from a German plane a few days after the Battle of Vimy Ridge while on reconnaissance mission with several other officers.

It was his second time being wounded in action, after suffering a minor injury on July 12, 1916 during the Battle of the Somme.

He was evacuated to London to recover, and then reassigned to command the Canadian engineering school at Bexhill.

That would end Campbell's engagement in the European theatre of the war. But by October 1918, he was in Victoria awaiting an assignment which would take to the far eastern side of the Eurasian continent...

The Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force was organized to bolster the "White Russian" forces fighting the Bolshevik "Reds" during the Russian Civil War. After the Bolshevik revolution in November 1917, Russia was in chaos and the country was divided into fighting factions.

"At the same time, Germany continued to press eastwards, threatening to capture vast quantities of Allied materiel, stockpiled at Archangel and Murmansk in the north and at Vladivostok in the east," military historian Ian C.D. Moffat wrote in a report titled Forgotten Battlefields -Canadians in Siberia 1918-1919. "The advance into south Russia also threatened to give the Germans control of the Russian 'breadbasket,' thereby gaining access to food and raw materials desperately needed by Germany to continue the war."

It became clear allied military intervention was needed to prevent Germany from seizing the critical supplies it needed, but political wrangling between the Allies meant it wasn't until August 1918 that Japan, France, the United States and Britain agreed to send a combined military force to Siberia. The British, in turn, had already approached Canada to participate in the force.

The mission suffered from delay, politicking and shortages of manpower, equipment and transportation. Although the first British troops arrived in Vladivostok, Russia from Hong Kong on Aug. 3, 1918, the advance party of 706 Canadian troops didn't arrive at the Siberian port until Oct. 26, 1918.

While the main force of the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force was being formed in Vancouver, the advance group had arrived in Victoria on Oct. 3, 1918, Moffat wrote. Because Campbell was in Victoria, it is likely he was part of the advance group which included the headquarters staff and support services including administration, medical support, logistics and food preparation.

Sixteen days after Campbell and the advance group of Canadians arrived in Vladivostok, the First World War ended with an armistice between Germany and the Allies.

"However, the only impact the armistice had upon the forces intervening in Russia was to change the status of the enemy," Moffat wrote. "It also started the political manoeuvring between the Canadian government and the British to evacuate the Canadian contingent back to Canada."

While political wrangling continued, the remaining 5,000 troops of the main Canadian contingent were trained in Vancouver and Victoria, and sent to Vladivostok throughout the fall and winter of 1918. Some members of the 259th Battalion mutinied and refused to board ships headed for Russia, resulting in 12 arrests while the other soldiers were marched aboard at bayonet point, Moffat wrote.

The troops in Siberia saw little action, with some serving as train guards but most conducting routine sentry duties in Vladivostok.

Col. Louis Keene took advantage of the time to paint several pictures of Canadians on duty in Siberia.

The only combat deployment for the Canadians was in a village called Shkotova, north of Vladivostok, Moffat wrote.

"On April 12, 1919, Bolsheviks surrounded the village where Russian troops, loyal to (White Russian leader Admiral Aleksandr Vasilyevich Kolchak), were holding prisoners. It was feared that the Bolsheviks would capture the whole village and endanger the mine in the vicinity. The Japanese commander called for an Allied force to rescue the Russians in the village, but the Americans refused to take part," Moffat wrote. "The Canadians sent a company from the 259th Battalion to be part of the rescue force. However, when they arrived at the village on April 19, the Bolsheviks had already dispersed, and the force returned to Vladivostok two days later without having fired a shot."

The Canadian forces began their withdraw from Siberia a few days late on April 22, and the last Canadians left Vladivostok on June 5, 1919.

A total of 17 Canadian troops died during the Siberian mission, with 14 buried at the Churkin Naval Cemetery in Vladivostok.

Campbell survived the war and moved back to Prince George, where he lived until his death at the ripe old age of 94 on June 6, 1982, according to an obituary in the June 9, 1982 edition of The Citizen.

Campbell volunteered for military service again during the Second World War, and served at a Canadian Army supply depot. Between and after the wars, he returned to his work as a surveyor, surveying municipal lots until his retirement in 1970.

"Mr. Campbell was born at Collingwood, Ont. in 1888 and moved with his family to Victoria in 1891 and arrived in Prince George with a survey party working on the Grand Trunk Railway in 1903," The Citizen reported. "He was predeceased by his wife... in 1981 and is survived by his many nieces and nephews in Victoria."

In addition to the Military Cross, he was awarded Croix de Guerre by the French government in July 1917 for his service.