Canadian officials took longer than any country to collect, analyze and submit bird flu samples to an international database that allows scientists to track the genetic evolution of highly infectious strains of the H5N1 virus, a new study has found.

Published in the journal Nature Biotechnology Tuesday, the study analyzed the time it took to collect and upload genetic information from samples of H5N1 to the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID), a repository for virus data.

The University of British Columbia researchers then analyzed the timelines for 28 countries, which together, uploaded 19,000 samples between 2021 and 2024. On average, it took 228 days to upload the wildlife samples.

Some countries, like the Netherlands and Czech Republic, shared results within a month, said lead author and UBC zoology professor Sarah Otto.

Canada was found to be the slowest at 618 days.

“That's nearly two years,” said Otto. “We don't know where the delays are. All I can say is it's pretty bad.”

Bird flu having major impact on agriculture

During the COVID-19 pandemic, health authorities found ways to speed up the time it took to sample and share anonymized test data so scientists could track the genetic evolution of the virus. On the human side, the time it takes to sample a COVID-19 case and post the data to the web takes an average of 16 days, down from 88. Canada is now a global leader, said Otto.

But the researcher said those lessons don’t appear to have filtered down to Agriculture Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

“I couldn’t see what was happening evolutionary in the last few months because the data was old,” Otto said.

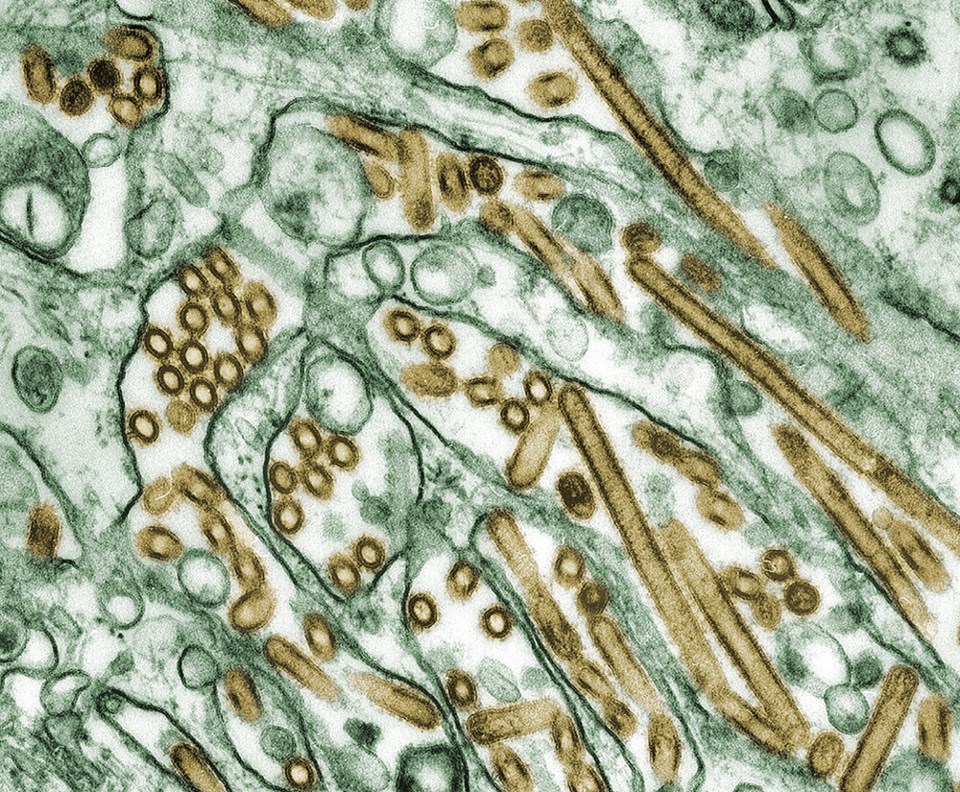

Highly pathogenic strains of the H5N1 virus have spread rapidly in recent years, first through wild bird populations and then into poultry farms. When the virus enters a poultry farm, they often find the immunologically naive bird populations that haven't had time to evolve any resistance, according to Ronald Ydenberg, a professor of behavioural ecology and director of Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Wildlife Ecology.

British Columbia’s poultry farms have been hit harder than any other province. As of Feb. 25, 8.7 million domestic birds were culled in B.C. That represents 60 per cent of the 14.5 million birds culled across Canada since late 2021, when the first reported case of the highly contagious strain was found in the country.

In the U.S., the virus has increasingly been found in cattle. As of this week, 70 cases were reported in humans. One person is known to have died of the disease in Texas, while a young man in B.C. fell significantly ill with the virus before recovering, health officials said.

A small window to detect potential mutations

Currently, Otto says the virus appears to be spread through touch. Scientists are carefully monitoring for any signs that H5N1 could mutate and be transmitted through the air or between humans.

“Scientists don't have a crystal little ball about whether or not this virus can evolve and adapt for human-to-human transmission,” said Otto.

They also don't know the routes the virus might one day take to infect humans. But the more species it spreads through, the more chances it has to evolve.

“There's a really small window of time that we have to act if it does change. We need to be able to figure out where that change is and isolate it, and find the wild populations that may be harbouring the changes that we're worried about,” said Otto.

But if that information is not posted for two years, scientists won't be able to act fast enough.

“It's going to be too late,” Otto said.

Canada's size, overlapping jurisdictions cause delays, says agency

A spokesperson for CFIA said sample collection, testing and sharing information to the international database can be delayed because of a number of factors, including testing priorities, the number of collaborators involved and “Canada’s vast size.”

“In Canada, samples are collected by hundreds of people from dozens of agencies, including the most remote regions,” said the spokesperson in an email.

For domestic poultry, timelines range from two to three weeks, said the spokesperson. But for wildlife, it can be “highly variable and delays are possible.” When virus surveillance turns up large number of domestic bird samples, the volume can put wildlife testing on hold, according to CFIA.

Any time a genomic sequence provides new insights into the behaviour of the virus, it is made public as a soon as possible, the agency added. When a viral variant that confers drug resistance was recently found on a poultry farm in British Columbia, the complete viral genome was made public within 13 days of swabbing a bird’s throat, the spokesperson said.

Ralph Pantophlet, a professor specializing in infectious disease and immunology at Simon Fraser University, said there’s a real possibility that Canada’s vast geography, lack of manpower and overlapping jurisdictions are slowing the collection of bird flu genome data.

Pantophlet, who wasn’t involved in the research, said there is also a possibility that some data is being shared to other genetic databases outside of the scope of the study. Still, he said, the fact that Canada has fallen so far behind other countries is concerning.

“The public health risk could be significant if there are delays in getting this type of information out,” Pantophlet said. “There should be some kind of review.”