A B.C. professor would like to see a robot take your vitals when you visit a doctor in the somewhat near future.

Dr. Woo Soo Kim, associate professor of mechatronic systems engineering at Simon Fraser University, has developed health care robots that can measure heart rate, respiration rate, temperature and oxygen levels. The oxygen level measurement in particular could be used to monitor severe COVID-19 patients.

He hopes the sensor robots can support doctors and nurses, and is currently using two prototypes to collaborate with a team of Vancouver Coastal Health researchers on how a technology like this could be applied in practice.

There’s a lot to be worked out — including how comfortable will patients be receiving care from a robot – but Kim hopes to have sensing robots in health care in five to 10 years. He imagines a full complement of medical care robots, including passive bots that take vitals, companion bots that would hang out with patients to regularly monitor vitals so people don’t need to wear an uncomfortable device, and even receptionist bots.

We might already be warming up to machine-based medical care, as a recent report indicated most British Columbians now prefer virtual meetings with their doctors for routine check ups.

His lab, Additive Manufacturing in SFU’s Surrey campus, has been working on advanced 3D printing, wearable technology and sensing robots since he arrived in 2010, and narrowed their focus health care uses in 2018. He works with six to seven students and interns.

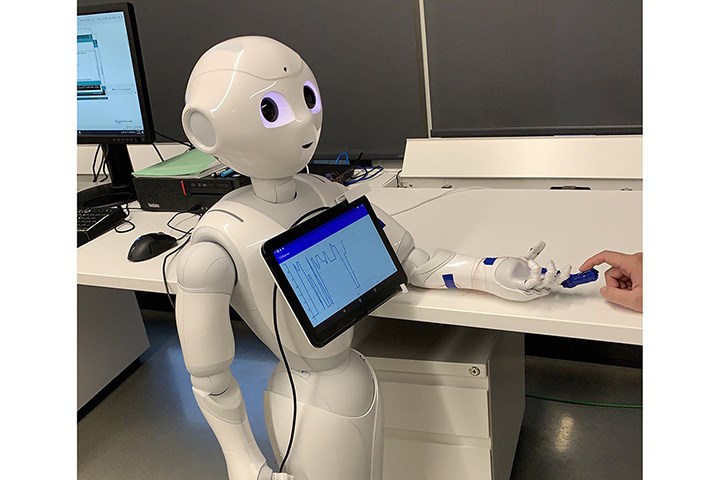

Now they have two working prototypes to take to doctors and nurses. One is an arm, completely made in the lab with 3D printed origami. The second machine is a shiny, white humanoid that Kim’s lab has added on their own hand with highly specialized electron sensors.

The origami design was chosen not just because it’s cool. His lab has spent years testing various architectural solids with 3D printing, and found that “3D origami structures have naturally less fatigue characteristics with re-configurable structures. So, it’s good if they are used for bending structures such as our fingers,” Kim said.

Funding has been partially provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the lab is applying for more grants to expand development.

The first stage of robotic health care is passive, with the machines gathering information and sharing results with human health care professionals, but Kim envisions future machines that could be more involved.