Across nearly all of Canada’s largest cities, urban trees and their cooling effects are more concentrated in rich, white neighbourhoods, a new study has confirmed.

The research, recently released from Nature Canada, analyzed tree canopy maps across 12 Canadian municipalities, including Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto and Montreal.

In each case, the report found that in poorer and more racialized communities, trees were more scarce and shade was at a premium.

“What I think we’re seeing is the lived experience of racism in Canada,” said Hannah Dean, who oversaw the report as Nature Canada’s organizing director.

“We’re seeing values and priorities play out in real-time in the way our neighbourhoods and people are cared for by our municipalities.”

Scientists are still trying to document the consequences of being removed from green spaces.

Living near trees has been associated with a number of benefits, from reducing rates of cardiovascular disease, dementia and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), to increasing physical activity and social cohesion, to improving developmental benchmark scores for young children.

When it comes to surviving the impacts of climate change and extreme weather, trees provide a buffer from wind and cold.

One of the biggest benefits of urban forests comes during heat waves. Through a process of evapotranspiration, trees pull water through their roots and up their trunks. Coursing through a tree's limbs, the water eventually escapes a leaf or needle as vapour, instantly dropping ambient temperatures.

In a well-treed neighbourhood, trees have been found to cool urban environments by as much as seven degrees Celsius.

A clear trend extends to B.C.

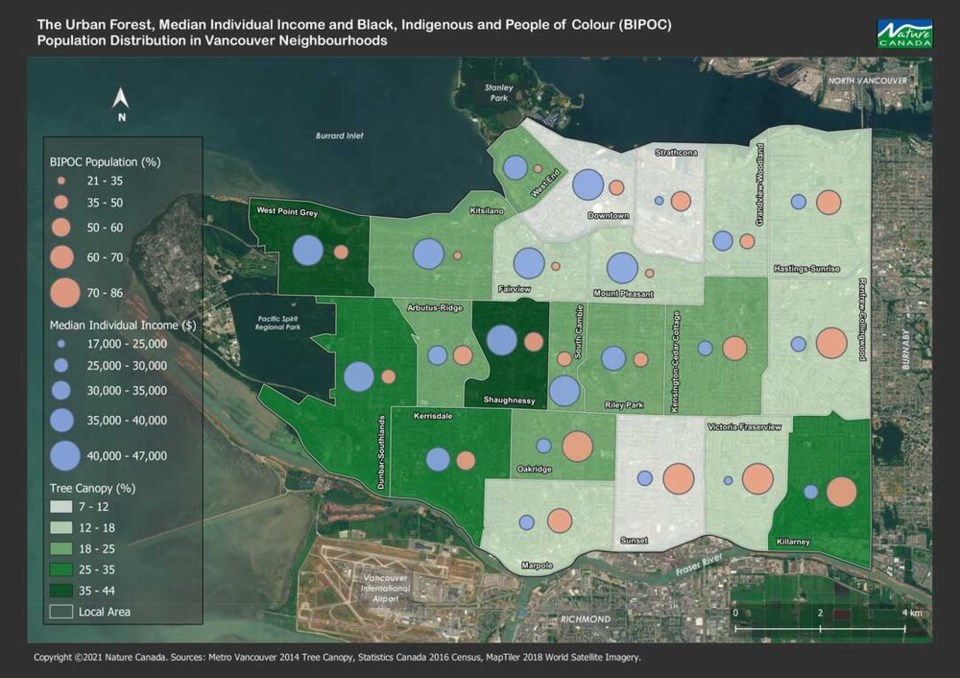

To understand how trees are dispersed across Canadian cities, the researchers combined census data with LiDAR scans — which create 3D elevation maps by bouncing a laser from an aircraft to the ground — to map the relationship between tree cover, income and race.

In B.C., the report looked at the cities of Burnaby, Richmond, Surrey, Abbotsford and Vancouver (a deeper analysis was reserved for the latter two).

Nearly every city followed the same pattern: the more people of colour and lower the income, the fewer trees stand in a given city neighbourhood.

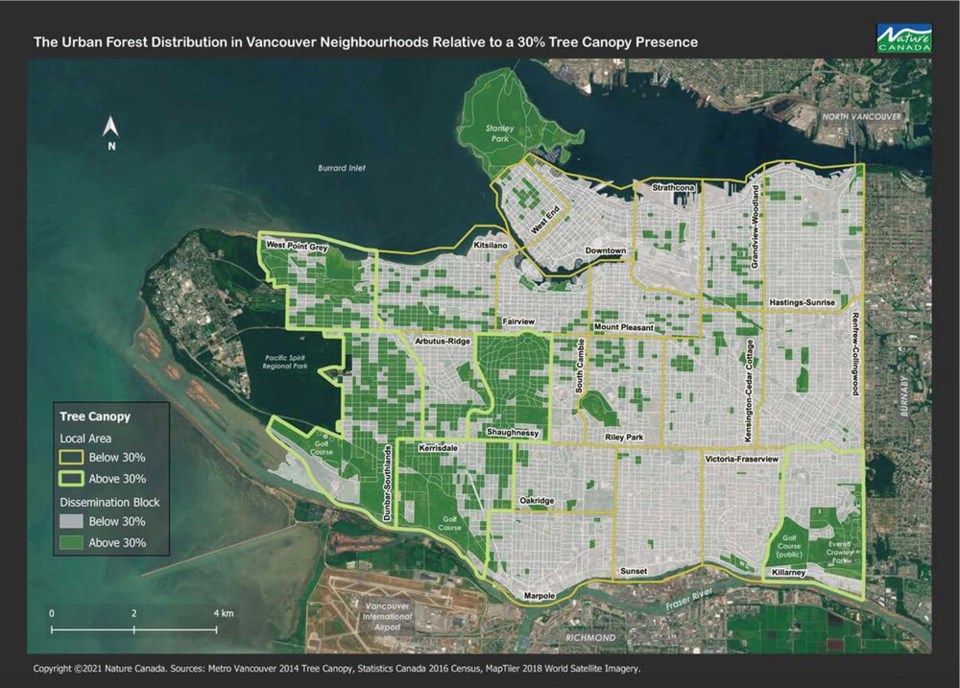

In one map, the researchers mapped where in Vancouver tree canopy cover met the 30 per cent recommended threshold. While in the west of the city, large swathes of neighbourhood blocks met the cut-off, in the east, only the neighbourhood of Killarney — home to a golf course and big park — met the bar.

The Nature Canada study reaffirmed reporting carried out by Glacier Media during last year’s heat dome.

When record heat hit B.C. in June 2021, temperatures soared in Vancouver neighbourhoods where trees are scarce.

In some neighbourhoods with relatively little tree cover, like Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, emergency visits due to heat illness tripled relative to more affluent, treed areas, according to the Glacier Media investigation.

Those patterns line up with mapping from Nature Canada, which show big east-west divides, in which urban forests favour relatively wealthy and white neighbourhoods.

“Where things are currently standing, there's still a lot of work to be done,” said Dean of B.C.'s largest municipality.

Richmond stood out among B.C. cities with a 12 per cent tree canopy cover — the second lowest of all the cities measured.

Burnaby, on the other hand, was slightly distinct from many of the cities in the study. While tree cover was found to be lower in racialized neighbourhoods, lower-income communities were found to have higher access to urban forests.

Up valley in Abbotsford, over a third of the city’s roughly 140,000 residents identify as Black, Indigenous, or as a person of colour.

Excluding agricultural lands, 40 per cent of the city is covered in trees. A third of that is concentrated in a small pocket of neighbourhoods where Abbotsford’s richest live.

In the city centre and central west, low-income populations with a relatively high number of people of colour live in areas with relatively low tree cover.

The city is still trying to figure out what targets it wants to set for tree canopy cover, though proposals are currently suggesting either maintaining or reducing current levels, notes the report.

Elsewhere in Canada, part of the challenge in closing the urban tree cover gap comes down to geography.

At eight per cent, Calgary has the lowest tree canopy cover of any large Canadian city. But that's made even worse on the west side of the city, where relatively racialized neighbourhoods have been built on natural grasslands unsuitable for planting trees.

The city has plans to plant 7,500 trees a year and eventually raise its tree canopy to 16 per cent by 2060. But according to the report, it's not on track to meet that goal.

“It is environmental racism on the neighbourhood level,” Dean said of the results in city after city. “This hasn't been prioritized. And this hasn't been spoken about and really examined. Because that's just the way that racism has played out.”

How to close the shady divide

In the second part of their analysis, the report’s authors sought out an “insider’s perspective” on how to fix the gaps in tree canopy coverage.

Honing in on Canada’s three largest cities — plus Ottawa, Winnipeg and London — they interviewed a number of municipal staff, urban foresters, academics and people in the field to understand how and why trees were unevenly distributed.

One lesson, says Dean: the federal government’s pledge to plant two billion trees by 2030 offers a “massive opportunity” to close the neighbourhood gap in urban tree cover.

But first, she said, cities need to know where those gaps are. Several of the LiDAR maps used for several B.C. cities are already eight years old.

Through interviews, the Nature Canada study concluded the gaps in tree canopy cover result from a lack of funding, poor incentives to plant trees on private land, a failure to launch integrated planning processes that values trees, and weak public engagement in communities that need trees most.

Many Canadian cities have set what seem to be ambitious targets to plant more trees. In Toronto, the city has said it will achieve 40 per cent forest cover by mid-century, and in Vancouver, council approved a new city-wide target of 30 per cent canopy cover by that date.

Those kinds of targets, however, fail to ensure the least tree-covered neighbourhoods get the most attention, concluded the report.

Instead, it recommends cities set goals following a “3-30-300 rule,” which ensures:

- all residents can see at least three trees from their homes;

- every neighbourhood has at least 30 per cent tree canopy over;

- and that citizens can access a green space within 300 metres of where they live.

At the community level, the Nature Canada report says individuals need to put more pressure on local politicians.

For city staff, planting trees should not be an afterthought of development; rather, urban forestry should be integrated into a planning process that includes marginalized neighbourhoods from the start, recommends the report.

But the benefits of more green spaces go beyond humans: by planting more trees, municipalities can help reconnect urban and suburban landscapes fragmented by agricultural and city building.

“It’s really important habitat,” said Dean. “We see massive declining populations of migratory birds and other bird species in Canada that need trees in that habitat to survive.”

At the federal level, the report recommends Ottawa’s plan to plant two billion trees by 2030 should prioritize urban, near-urban and agricultural lands.

To meet that demand would require a massive scaling up of nursery capabilities across the country. More federal funding is also required at the city level, says Dean, as cities only have so many resources to keep the trees they already have alive.

It will not be easy, the authors of the report heard from a number of experts and city planning staff. Planting more trees in cities presents some unique challenges compared to planting a logging cut block or wildfire-scarred hillside.

Breaking open concrete surfaces and planting around underground infrastructure is an obvious challenge to planting trees in the city. But the report also highlights “conflicting interests,” where utility providers and real estate developers often push back against city planners, while not recognizing the ecological benefits of urban forests.

Another barrier — in a housing crisis, affordable housing is being prioritized over trees.

On the other hand, notes the report, prioritizing trees could have huge knock-on effects. For every dollar spent on a tree, cities are forecast to receive benefits worth between $2 and $13.