Canada’s forestry sector has emitted more than 90 million tonnes of greenhouse gases every year for the past 17 years, a new study has found.

The research, published in the peer-reviewed journal Frontiers in Forests and Global Change this month, found that between 2005 and 2021, the country's national inventory report said forests in Canada absorbed just shy of five million tonnes a year.

Not only did the forestry sector’s carbon pollution go completely unreported, it reached levels similar to the electricity sector. Total area logged, the study found, was a “significant predictor of net forestry emissions.”

“Canada’s ability to meet its emission reduction targets will be compromised until it recognizes and addresses the full scale of emissions from commercial forestry,” Anthony Taylor, co-author and associate professor at the University of New Brunswick, said in a statement.

'A shell game'

With nearly 362 million hectares of forests, Canada is the third most forested country in the world. But after years of being a net carbon sink, in recent years, Canadian forests have been adding more carbon to the atmosphere than they absorb.

But those numbers are not being accurately reported to both the Canadian public and United Nations, which tallies countries' emissions as they seek to reduce them.

The researchers said the discrepancy in emissions data comes from the way the government reports wildfire emissions.

Carbon pollution from wildfires is not counted because it’s considered “natural.” But once forests grow back — reaching commercial maturity at 76 years old — the government inventory starts to count all the carbon trees suck out of the atmosphere, explained Jay Malcolm, a study co-author and professor emeritus at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Forestry.

“That is the entire difference,” Malcolm said. “It's kind of a shell game.”

Miscounting emissions backs bad forestry policies

The findings come nearly nine months after an audit from Canada’s Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development found the federal government was significantly under counting emissions from the country’s forestry sector.

“The audit found that Natural Resources Canada, working with Environment and Climate Change Canada, did not provide a clear and complete picture of the role of forests in Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions, such as logging,” noted the office of Commissioner Jerry DeMarco in a March 2023 summary of the findings.

In a letter dated Dec. 3, 2023, 29 senators and members of Parliament wrote to Canada’s environment and natural resources ministers, calling on them to “more transparently report — and reduce — GHG emissions attributable to Canada’s logging sector.”

The latest peer-reviewed study adds urgency to that call. It concludes that miscounting emissions from forests could be providing cover for “misaligned policy incentives.”

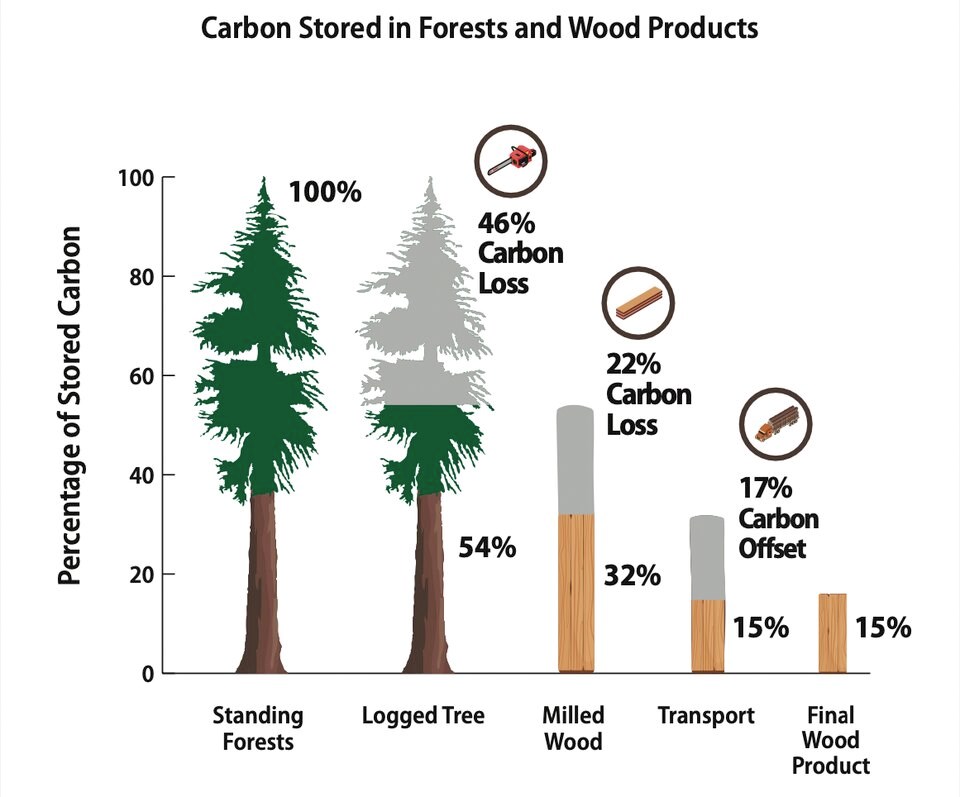

“For example, arguments that forests better serve emissions reduction targets when logged and put into harvested wood products or burned as biomass depend on several assumptions, including that the forestry sector has nearly zero or negative emissions,” noted the report.

But Malcolm said his team's analysis shows Canadian forests have clearly become a source of emissions at a time its ecosystems are being hit with a “double whammy” of clearcut logging and wildfires made worse by climate change.

The findings are of particular interest to B.C., a heartland of a timber industry that could reduce its emissions by better protecting old-growth forests and implementing longer harvest rotations, Malcolm said.

“We need to have a mix of strategies so we can keep more carbon in our forests,” he said.

“If you want to have a full accounting of what's going on in our forests, you need to bring that all together.”