Underlying the John Horgan government’s sweeping reforms to forestry are some laudable goals: saving stands of at-risk old growth, taking steps toward First Nation reconciliation, protecting caribou and addressing a long-term decline in B.C.’s timber supply.

But these reforms will cost B.C. between 4,500 and 12,000 jobs – depending on whose estimates you believe – and accelerate a flight of capital that has already seen B.C.’s forestry majors buying up sawmills in the U.S., Europe and Eastern Canada, while shuttering sawmills and pulp mills in B.C.

“We need certainty,” Don Kayne, president and CEO of Canfor Corp. (TSX:CFP) told BIV. “And if we don’t have that in British Columbia, we’re not investing.”

In a recent brief, RBC Capital Markets analyst Paul Quinn speculated that “sawmills will pull back on local investment given the uncertain future of forestry in B.C. The province has already moved from a low-cost producer to (by far) the highest cost region in North America over the past decade.”

“And we expect that trend will remain in the near term as mills continue to chase fewer and fewer logs.”

A growing chorus of voices – from forestry companies and chambers of commerce to union leaders and First Nations – is warning about the pace and scale of the changes and lack of consultation.

In addition to its recent announcement of plans to remove up to 2.6 million hectares of old growth from the timber harvesting land base, the Horgan government used closure to shut down debate on two bills that could dramatically redraw the forestry landscape for B.C.’s forestry sector, which produces B.C.’s most valuable exports.

“The pace and scale of the policy and legislative changes that have been introduced in the last five weeks has been unprecedented,” said Susan Yurkovich, president of the Council of Forest Industries (COFI).

“The government is rushing through legislation with things that will have fundamental impacts on communities, on First Nations, on forestry companies, on workers throughout the province with very little discussion in the House.”

Even some First Nations – among intended beneficiaries of tenure reform – say the changes are being rushed and that they have not been given the time or resources to properly respond to what’s proposed.

“The province is making sweeping changes to forest legislation without any substantial First Nations input,” the BC First Nations Forestry Council says.

The B.C. government gave First Nations only 30 days to respond to its proposed old-growth deferrals. The Huu-ay-aht on Vancouver Island responded (it disagrees with the deferrals), while others protested the tight deadline.

“We don’t have the resources or expertise needed to understand the implications of these changes on our rights,” the Ashcroft Indian Band told the government.

The United Steelworkers union (USW), which represents 12,000 sawmill workers and loggers in B.C., has also criticized the reform legislation – notably the old-growth deferrals – as hasty and lacking input from labour.

“In the past three years, eight operations with USW workers across B.C. closed and 1,000 good-paying, family-supporting jobs were lost,” said USW Wood Council chairman Jeff Bromley. “The impact from this process will almost certainly multiply across the province.”

While rural communities could be hit hard by reforms that result in sawmill and pulp mill closures, even cities like Surrey could see significant economic impacts.

Large sawmills in Surrey include operations run by Teal-Jones Group, S&R Sawmills, Pacific Lumber, Catalyst Paper, the Sundher Group, Key West Forest Products and Riverside Forest Products.

“The deferral process is going to jeopardize many businesses,” said Surrey Board of Trade president Anita Huberman. “Hundreds of employees will be laid off due to this deferral process.”

In his recent brief, Quinn estimated the removal of 2.6 million hectares of old growth from the timber land base would translate into a 13% decrease in the annual allowable cut (AAC).

Old growth makes up a relatively small amount of Teal Jones’ tenure, but is disproportionately valuable.

“Those small quantities allow us to go into areas of some of the lower-quality fibre so we can harvest the whole scope of the forest,” said Conrad Browne, director of Indigenous partnerships and strategic relations for Teal Jones.

While old-growth logging deferrals are the most immediate concern, other changes being made – through bills 23 and 28 – will redraw the working forest land base in B.C. and could have a serious impact on forest industries.

Those changes have been rushed through the B.C. legislature without sufficient debate, said BC Liberal forestry critic John Rustad.

“It took me six hours to read this legislation once,” said Dave Elstone, managing director of the Spar Tree Group forestry consulting firm. “How on earth can they have passed this in the legislature that fast? There’s no way you could have sat down and understood this as an MLA. I’m a forester, and I have to sit down and really think about this stuff.”

Bromley said unionized labour has likewise not had sufficient input on all the changes.

The amendments made to the Forest Act include mechanisms for redistributing tenure.

“Changes to legislation will enable the government to reduce harvesting rights of established companies that have built up world-class sawmills and plywood mills over the decades,” warns forest sector consultant Russ Taylor.

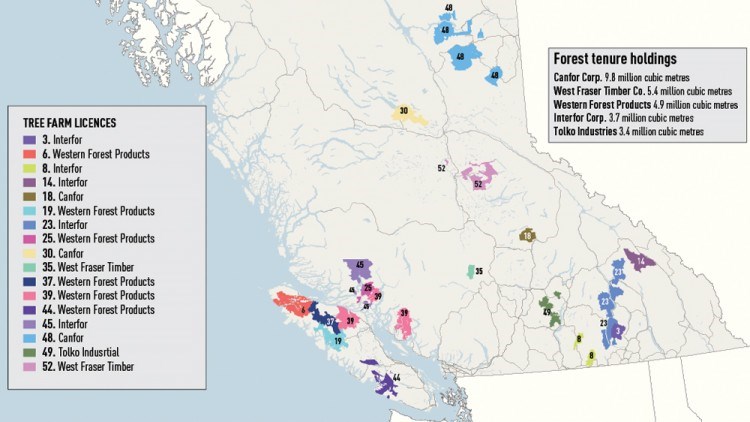

Katrine Conroy, Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, acknowledged that old-growth deferrals could cost 4,500 jobs. But Taylor estimated that “the compounding effect” of old-growth deferrals, tenure redistribution and other reforms could result in the permanent loss of 10 to 12 sawmills, 10,000 to 12,000 jobs and more than $400 million in annual government revenues. COFI warns job losses could be high as 18,000.

Loss of B.C. mills

The Liberals have lately made some political hay of Horgan’s pre-election promise in 2017 – made in the wake of a Tolko sawmill closure – that such a closure would never happen under a BC NDP government.

Since the NDP came to power in 2017, 11 sawmills, one oriented-strand board plant and two pulp and paper mills have permanently shut down in B.C., although one new sawmill was started in Port Alberni and another restarted in Quesnel, according to industry consultant Jim Girvan.

A total of 44 sawmills have been shuttered since 2005, which means the previous BC Liberal government also presided over dozens of sawmill closures.

The most recent mill to go down was the Catalyst paper mill, owned by Paper Excellence, in Powell River. The loss of a sawmill hurts, but when a pulp mill shuts down, it can be devastating for a small resource town like Powell River, because pulp and paper mills provide both high-paying jobs and substantial industrial taxes.

Powell River Mayor Dave Formosa said the paper mill’s permanent closure means the loss of 420 good-paying jobs. Paper Excellence had shut down two paper machines and restarted one, which employed 206 people, before announcing the mill’s “indefinite” closure.

Mackenzie has also lost more than 400 jobs since 2019. Canfor closed its sawmill there in 2019, and in 2020 the Paper Excellence pulp and paper mill permanently shut down. In 2022 Mackenzie’s tax base will lose $1 million as a result of the Paper Excellence mill closure.

But Mackenzie Mayor Joan Atkinson is not among those criticizing the Horgan government’s forestry reforms. She thinks tenure redistribution could be a good thing for Mackenzie if it means other smaller players will get access to local timber.

Canfor still holds a million cubic metres of annual allowable cut (AAC) in the Mackenzie timber supply area, Atkinson said. The logs cut there now go to mills elsewhere in B.C.

“I’m very supportive of the changes that the NDP government have brought forward, because in my mind big businesses have too much control of forests,” said Atkinson, who ran as an NDP candidate in the 2020 election. “Bill 28 is going to give better security to small communities because of their tenure take-back. It’s going to support communities, First Nations and BC Timber Sales, which opens up the availability to many more people than one large tenure holder who doesn’t even process one log in this community.”