Kim Gullion-Stewart, a former longtime local resident, will have her art in the collection at the Canadian Indigenous Art Centre in Gateneau Quebec, it was recently announced.

The centre has an extensive collection that includes more than 4,300 pieces.

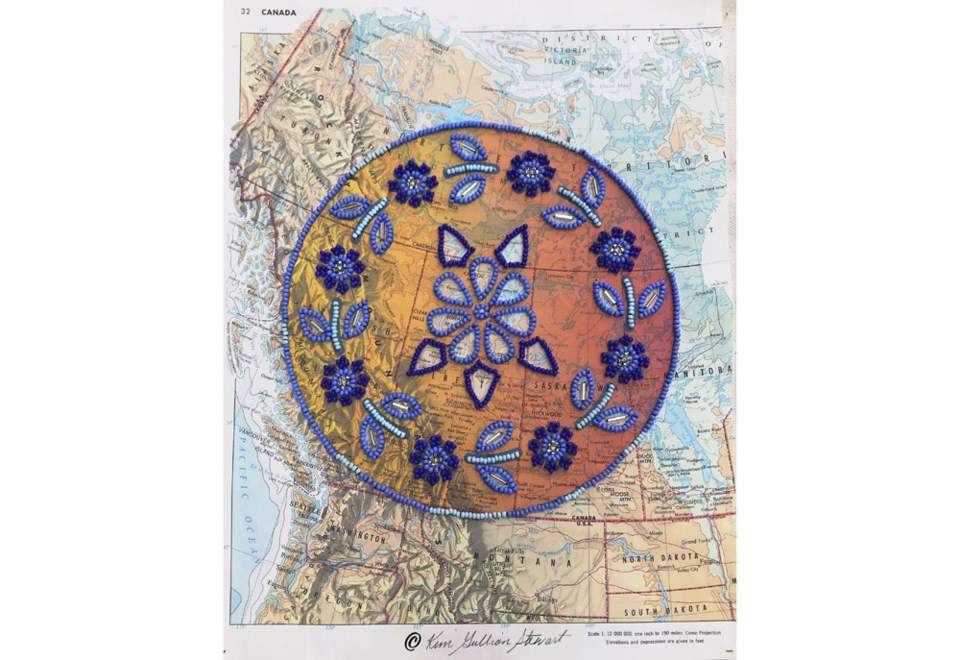

The piece is beadwork incorporated into a map that was torn from the pages of a 1950s school atlas book.

"I am really emotional and so humbled," Gullion-Stewart said about her piece going to the Art Centre.

"When I think about myself as that little kid who was just absolutely obsessed about drawing horses and things like that and then flash forward to today I am totally humbled that this beauty and these ideas are going to be preserved and be available not just for my piece but for all the pieces."

The art centre preserves, exhibits and promotes Canadian Indigenous arts through their gallery and often lends out the pieces to galleries across Canada for exhibition and education purposes.

Gullion-Stewart said she had a Grade 12 art teacher that was very influential in her life and told her that she could make a career in art, which sent her on her journey to making that a reality.

She attended MacEwen University in Edmonton for two years for fine arts when it was still a college and met her husband, took a bit of a hiatus and then returned to school for graphic design and illustration in Vancouver at Capilano University. Since then, she has enjoyed a 25-year career as a graphic designer and illustrator in and around Vancouver, spent some time in Whitehorse and Tumbler Ridge and then settled in Prince George for 22 years.

She was UNBC’s first publications officer and was in that job for about five years and then she took time off to home school her children. Gullion-Stewart then went to work at CNC where she taught in the fine arts, web and graphic design and Indigenous Studies programs and she still teaches for them online, at a distance.

She moved to Kamloops two years ago.

She teaches Metis Studies, a program she developed for the college as a university transfer course and there are two courses.

"In the second one I teach beadworking," Gullion-Stewart said. "The students get an art kit and they get to learn how to recreate some of the things that were made by Metis people during the fur trade and I use that as a way to teach the students about the economics at the time and Metis identity. So they learn how to do beadworking and caribou-hair tufting and finger weaving."

When Gullion-Stewart starting teaching at CNC, she got her masters degree in art education at Simon Fraser University.

She's been at the college full time for about 13 years and now enjoys working there part time from a distance.

Gullion-Stewart learned how to do beadwork from elder Alberta 20-Stands in 1996 in Tumbler Ridge.

"She was from Montana and came to live in Tumbler Ridge for a time - of all places - and she taught me how to create using a Metis art form," Gullion-Stewart said. "That was something I'd never done before."

After living in Tumbler Ridge, Gullion-Stewart moved to Prince George and became a member of the Nechako-Fraser Metis Association, as it was known then.

She was a women's wellness worker and she got a Canada Council of the Arts grant to teach women how to do hide tanning.

She had many elders who mentored her throughout her life, she added.

Gullion-Stewart fondly remembers reaching out to youth at risk during a community outreach program here in Prince George where she taught 25 youth how to tan hides through another grant from the Canada Arts Council.

"It was a lot of fun," Gullion-Stewart recalled. "So that kind of set me on this whole journey of exploring what wellness looks like in our Metis and Indigenous communities and how our art forms are connected to our personal well being."

The beadwork piece that will now be part of the Indigenous collection at the art centre speaks to that for Gullion-Stewart.

It's part of a series she is currently working on.

"It's based on a counter-mapping idea," she said. "Counter-mapping is where communities will take a traditional map created by a cartographer and will put their own marks of meaning - so it might be the trail to Johnny's house and that was put over top of these maps to kind of bring meaning to themselves and to their community."

When Gullion-Stewart saw some of those maps she decided to put her own spin on maps when she got Dent's Canadian school atlas books from the 1950s.

"I started taking sheets directly out of those vintage school books and beading on top of them," Gullion-Stewart said. "The idea was beading over top of areas that are marked out as provinces and territories while I know my ancestors had no notion of borders. As Metis people I had my great granny who was part of the Metis buffalo hunt in Saskatchewan."

How the Metis used the land was very different from the maps used during that time, she added.

"So I thought I would map over top of it using my beadwork because if you look into why Metis women decorated so much of their garments - it had a lot to do with the wellness of the community, showing respect for the land, the flowers and medicinal plants that grew. So I've chosen a couple of different flowers in this particular piece that I beaded right over top of the map of British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan."

The piece is called They Make a Well Beaten Path.

The map is attached to a piece of linen and the beadwork is done over the map.

"It's super satisfying and meaningful for me," Gullion-Stewart said. "It's very exciting to have my piece join all of these other pieces and I am humbled at the idea that they are going to take care of them and preserve them and make them available to people to see well into the future."