The Power of Forests Project, a BC-wide coalition of grassroots groups that want to see changes made to the province’s forestry industry, brought its plan for a new forestry act to Prince George on the weekend.

It was introduced at an event Saturday, Sept. 28 at UNBC’s Canfor Theatre, with retired forester Herb Hammond, Jennifer Houghton of the Boundary Forest Watershed Stewardship Society and Michelle Connolly of Conservation North, a volunteer-led group in Prince George, speaking.

Project organizers are calling for a new provincial forestry act, the primary objective of which would be to maintain the ecological integrity of forest ecosystems while developing community-based jobs as well as local economies that would strengthen the provincial economy.

“Without new legislation, industry is not motivated to shift from an industrial model to an ecological model. By focusing on ecological integrity, BC can conserve the benefits we get from forests and create more jobs in rural communities,” Houghton stated in a press release. “With 55,000 jobs lost in 20 years and all the damage being done, the current forestry system is not worth keeping. Legislation must safeguard the people and nature – our very survival depends on it.”

The new forest act would be focused on the protection and restoration of forests, Hammond said.

It would be based on nature-directed stewardship and involve representation by Indigenous and non-Indigenous governments, with community forest boards established to guide and direct timber management.

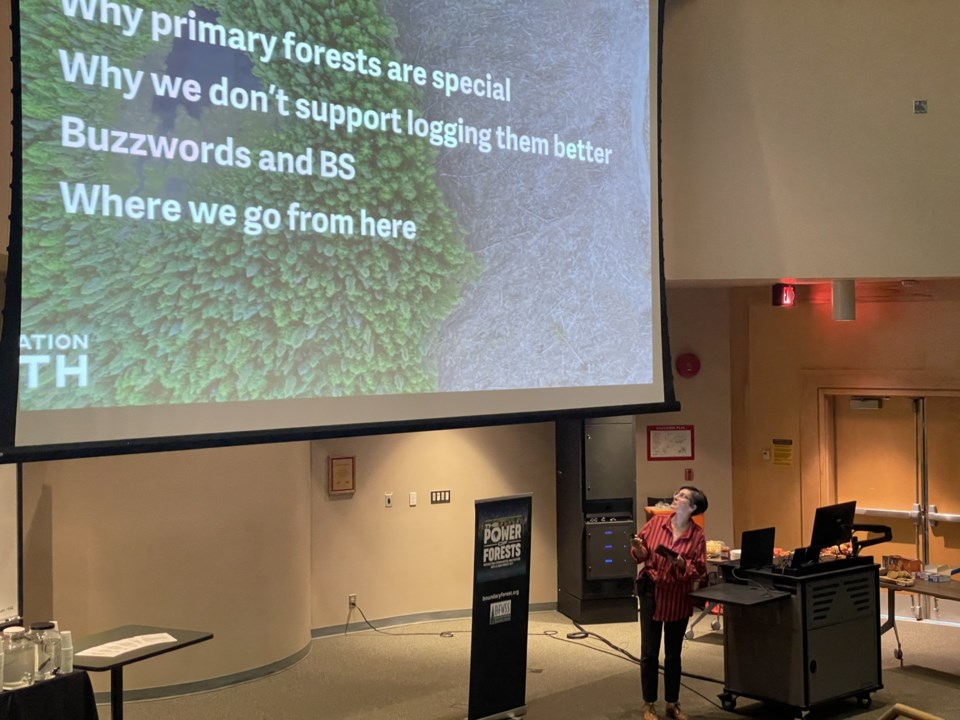

Connolly opened the session with a primer on the current state of BC forests and an exploration of modern commercial practices.

She’s critical of “salvage logging,” the practice of cutting down forests that have been attacked by beetles.

“The beetle is the trojan horse most of the time,” she said. “These are commercial decisions, not ecological ones.”

She then pointed out that forests have managed to survive and revive after fires and beetle outbreaks for centuries, and will do so again. She’s critical of the idea that a beetle infestation means a forest has to be culled. “You can’t log your way out of a beetle outbreak,” she said.

Connolly explained the importance of not only old growth, but the accumulation of dead, fallen trees in BC forests.

This blanket of decaying wood is vital for forest ecosystems, she explained. Natural forests have generations of rotten old trees that sustain many forms of life.

“Like voles and mice, the basis of the food chain,” she said.

Unfortunately, she said, the modern practice of cutting and replanting doesn’t preserve this part of the forest. “It takes several more generations of trees to recreate the forest floor we need,” she said. “But small mammals don’t have that time.”

Hammond, a forester and author, discussed the need for “nature-directed” planning. In other words, follow the forest’s lead rather than try to overmanage it.

He also discussed the decayed wood lining forest floors, but from a different angle. He noted that decayed wood is a key source of water and air filtration. “Decayed wood holds 20 times more water than a sandy soil,” he said. “When you lose that, you lose that function.”

It also heightens the risk of wildfires, he added, as the cleared forests are replanted but have lost that protective barrier.

These new forests don’t provide the same benefit as older forests. “The plantations are not forest,” he said. “They lack the diversity and function.”

Hammond said current practices aren’t working, which is why a new forestry act is needed, one that takes a more environmentally aware approach.

“Part of the reason we’re here today is to discuss policies and laws that will do exactly that,” he said, explaining that the laws until now have been designed based on anthropocentri, or human-centred, thinking, while what’s needed is “kincentric,” or earth-centred values.

“That’s a clear choice for us and we can design policies based on those,” he said. “Right now we’re clearly following the first one. We need a nature-directed path to a new relationship with forests.”

The goal, he said, would be to protect water supplies and diversify the economy, leading to employment in places like regional sort yards, where more accurate volumes and market rates can be determined.

“What it’s going to take is for everyone here who agrees with what we’re talking about to spread the word to other people,” he said. “What happened here today is a good step in the right direction. But it’s not going to happen by electing different political parties. It’s about connecting people in a new kind of social power so government has to listen.”

Schools will have a role to play, he said.

“The most important thing to do is get discussion and facts into the public education system,” he said. “The timber companies are visibly doing this. You can take forestry classes. But it’s forestry like what we’ve been talking about. It’s forestry that destroys.”

Taking questions from the audience, Connolly was asked how the proponents of a new forestry law can convince the forestry industry and governments that it’s viable.

“Can it continue to be an industry while it changes the way it’s managed?” she said. “Is there a way to sustain it while also implementing these changes? I personally don’t think the industry is going to look the same over the next few years.”

Recent downturns in the industry, something made clear by Canfor’s recent decision to close two BC mills and put 500 people out of work, make it clear the time is now, Connolly said. “As Canfor is getting ready to leave, we can decide the future we want.”