Embedded within the photo below is video, audio, a photo gallery, and a few extras to check out. Click on the icons to get to know Jane Inyallie a bit better.

The Health Arts Research Centre (HARC) at the University of Northern B.C. in the Northern Medical Program is exploring how art might positively affect health. This Art Heals series will show how Indigenous people, and their healthcare workers, have come to terms with emotional and physical trauma through a variety of art making in an effort to find a place of healing and peace.

If the Health Arts program had been around 27 years ago, Jane Inyallie might have been a participant.

Instead, because of the great changes she made in her life using art as a catalyst, she was invited to be on a panel filled with health professionals and arts practitioners who, during a public forum held earlier this year, explored how to connect creative arts, health and Indigenous perspectives.

Inyallie is living proof that art heals and she makes sure she can help others do the same.

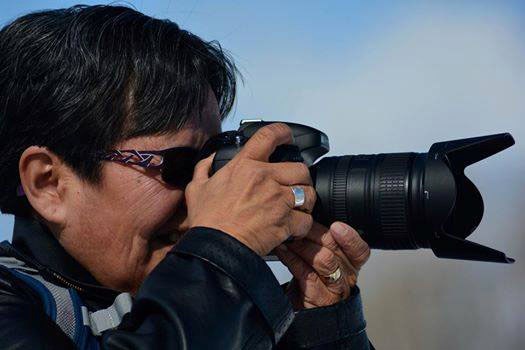

Inyallie, a residential school survivor, is now an addictions counselor, poet and photographer, who believes in the power of art and the beat of a drum to bring about healing.

Her first two efforts at dealing with her own demons inside a sweat lodge didn't work because she was too afraid.

The third time, instead of feeling the fear, Inyallie focused solely on the drum beat, a traditional First Nations art form, which touched a place deep within her that allowed the healing to begin.

Inyallie, now 60, was an alcoholic for many years before entering a program at Nenqayni Treatment Centre in Williams Lake in 1987 that included the sweat lodge therapy at Alkali Lake.

"Deep within the drum beat connected me to Mother Earth," said Inyallie. "After the sweat lodge I cried for three days because it released so much. It was very healing and an amazing journey, that period of my life."

That's when she started writing poetry. Before that she didn't feel like she had much of a voice.

"All of my work is written from experience, dreams and/or events that were pivotal points in my life," said Inyallie. She self-published a book of her work in 2011.

Inyallie is a member of the TseK'ehne First Nations, People of the Rock, and has two sons she's very proud of: Derek Orr, 40, who is chief of the McLeod Lake Indian Band and Darren Orr, 36, who is in sales and retail. Inyallie and Gayle Voszler have been in a life partnership for 20 years. Inyallie says that Voszler has always been very supportive of her, especially in all aspects of her photography, which she has had a keen interest in since she was 10 years old. Most days, Inyallie is out taking wildlife pictures during her lunch hour and after work, offering her an artistic outlet while communing with nature.

Inyallie spent her younger years in McLeod Lake.

"I lived with my grandmother and her husband - I don't like to call him my grandfather because he was very abusive to her," said Inyallie, whose mother and father and all their siblings went to residential school.

"And when I went to residential school I remember missing my community, my grandmother, my mother and my aunts," said Inyallie. "I just really missed home."

Inyallie attended Lejac residential school in Fraser Lake along with her cousins.

"I had a lot of fear being away from home," said Inyallie. "And it's really interesting that I have very few memories of actually being there. I don't remember being in the classroom. I remember all the bad things like being chased and getting strapped and no other memories. I think it's because of the trauma of being away from home."

Inyallie has done a lot of research on memory blocking and she knows that it's a matter of survival.

"If we can't deal with it, especially as children, we just don't remember," she said.

Inyallie did a lot of meditation in her late 30s and worked with an energy healer for about 25 years, a technique Inyallie incorporates into her work with patients at the Central Interior Native Health Society, where she's been a counselor for the last eight years.

"When I work with people I totally rely on intuition," said Inyallie, who took the Nechi Alcohol & Drug Training Program. "The best thing about it was that as you learn, you work through your own issues."

Between the healing energy practice and her formal training, it set the foundation for her life's work.

"I knew I wanted to work with people and I knew this was the area that I wanted to be involved in," said Inyallie, who tried bookkeeping and general office work before she found her niche.

At the Central Interior Native Health Society, a clinic that serves about 1,300 people in the heart of downtown Prince George, Inyallie works with people in four different stages of recovery. Those who are in active addiction, those thinking about making changes, people who are making a plan for their recovery and those who wish to maintain their recovery.

Every Wednesday morning, many of the 26 clinic staff members get together to brainstorm about patients who require more complex care. The meeting begins with a smudging ceremony to release any negative energy and allow healing, which is followed by a prayer.

"The staff member will present the patient's issues to the team and then as a group we will come up with ideas to try to help," said Inyallie, who has been a counsellor for about 20 years in total.

A great majority of the people who come to the clinic are residential school survivors so Inyallie believes she can be better described as a therapist who works with traumatized people.

"With most people who have had severe trauma, you don't really talk about that, so how I work with them is to focus on what's not working today - right now - and finding a way to help," said Inyallie.

Part of the system she has developed over the years includes getting the patient moving to combat the most common afflictions, including depression, anxiety, panic attacks and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

"I encourage them to do anything they like to do," said Inyallie, whose own daily therapy now includes wildlife photography. "If they like dancing, or drawing pictures, or painting, it seems to open them up toward a healing path. And that's where we start."