Buried deep in the platform the BC NDP released last week is a single line that could have long-term implications for government revenue and the natural gas and LNG industry.

The NDP commits to “a comprehensive review of oil and natural gas royalty credits.” Those credits, notably deep-well credits, have been assailed by the BC Green Party, anti-fossil fuel activist groups and sustainable-development think tanks as a fossil fuel subsidy that is no longer justifiable and costs the government hundreds of millions each year in forgone revenue.

Stand.earth recently published a report targeting B.C. fossil fuel subsidies – particularly the deep-well credits, although it also criticizes the B.C. government for policies to promote the province’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry. It echoes a previous report done by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), which has also criticized B.C.’s deep-well credits as a subsidy that surrenders too much government royalty revenue.

Both reports also questioned subsidies to B.C.’s nascent LNG industry, although the policies they point to are largely tax and electricity rates that all heavy industries pay – and some of them are incentives offered to companies to lower their greenhouse gas emissions.

What the NDP did with LNG tax policy was to cancel a suite of special taxes proposed by the previous Liberal government for the LNG sector – a special LNG tax, for example, and higher electricity rates – that no other industry in B.C. pays.

The one policy that may be harder to justify is the deep-well credit. Stand.earth estimates the credits alone amount to an annual subsidy to natural gas producers of $350 million, which is less than the government makes back annually on oil and gas royalties.

“While Premier [John] Horgan’s government spent $922 million on fossil fuel subsidies in its first year governing – an increase of 79% over what the BC Liberals spent – it took in only $241 million in oil and gas royalties,” the Stand report states. “The BC government needs to immediately cancel the deep-well royalty credit and embrace the federal government’s plan to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies by 2025.”

The B.C. government’s oil and gas royalties have dropped substantially over the past 10 years. The reason for the decline has more to do with natural gas prices than credits.

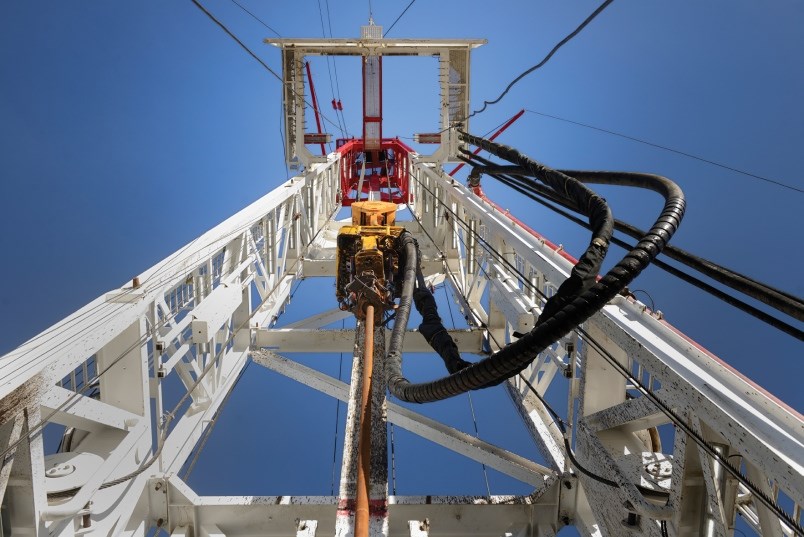

Natural gas prices have fallen to about one-quarter what they were in 2008, thanks to the abundance unlocked by unconventional extraction – horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing – in North America.

Indeed, the main rationale for developing an LNG industry in B.C. is to provide new markets for the province’s massive reserves of natural gas. It is assumed that those new markets will lift Canadian natural gas prices and increase royalty payments to the government.

More importantly, an LNG industry would generate new jobs and tax revenue. The Impact Assessment Agency of Canada calculated that the $40 billion LNG Canada project alone would generate up to $22 billion in tax revenue for the B.C. government over a 40-year period.

Determining what constitutes a subsidy can be tricky. And it can be difficult to determine if eliminating subsidies in one jurisdiction would create a disadvantage for producers compared with rivals in competing jurisdictions, resulting in “leakage.”

Deep-well credits are offered in B.C. because of the high cost and technical challenges associated with unconventional drilling. Wells can be two to three kilometres deep and cost $4 million to $5 million each.

But oil and gas companies often tell investors that the B.C. Montney region is one of the most prolific and low-cost gas plays in North America, thanks to its abundance of valuable natural gas liquids such as condensate and propane.

Would they really flee B.C. if the deep-well credits were axed, especially now that new markets may be opening up for LNG?

Geoff Morrison, manager of B.C. operations for the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), thinks they might. Producers could simply shift more production next door to Alberta.

“Is B.C.’s royalty regime competitive with other jurisdictions?” Morrison asked. “And the short answer is, without the royalty credits, they are not. You need the royalty credit system to be competitive with other jurisdictions.

“The fiscal regime in B.C. includes the carbon tax, the motor fuel tax and other costs that other jurisdictions don’t [have]. So you do need to compare the all-in fiscal regime when you’re looking at comparisons between jurisdictions.”

After the IISD looked at oil and gas sector subsidies in B.C., it concluded that the government should at least review, and better explain, its complex mix of tax credits and incentives to provide a clearer picture of just how much the natural gas industry is subsidized.

“It is clear that B.C.’s current royalty structure is resulting in low amounts collected and high amounts of forgone revenue,” the report notes. “It is worth examining whether existing royalty policies actually function to provide economic benefits for residents of the province.”

Asked if the LNG sector in B.C. is disproportionately subsidized, compared with other LNG-producing nations, Vanessa Corkal, policy analyst for the IISD, said that comparison hasn’t been done.

“Certainly LNG is heavily subsidized in other countries,” she said, and pointed to Russia, Australia, Argentina, Mozambique and the U.S. as examples.

Marvin Shaffer, adjunct professor at the School of Public Policy at Simon Fraser University, said incentives like deep-well credits need to be weighed against the benefits they produce.

“If it weren’t for the credits, assuming they are reasonably reflective of the higher costs of deep-well development, there wouldn’t be any royalties because there wouldn’t be any development and production,” he said.

“Having said that, there still is the question of whether the [government] should be encouraging deep-well and other high-cost development, which, because of the high cost and need for royalty relief, do not provide any significant return to the province from the extraction of the resource.”