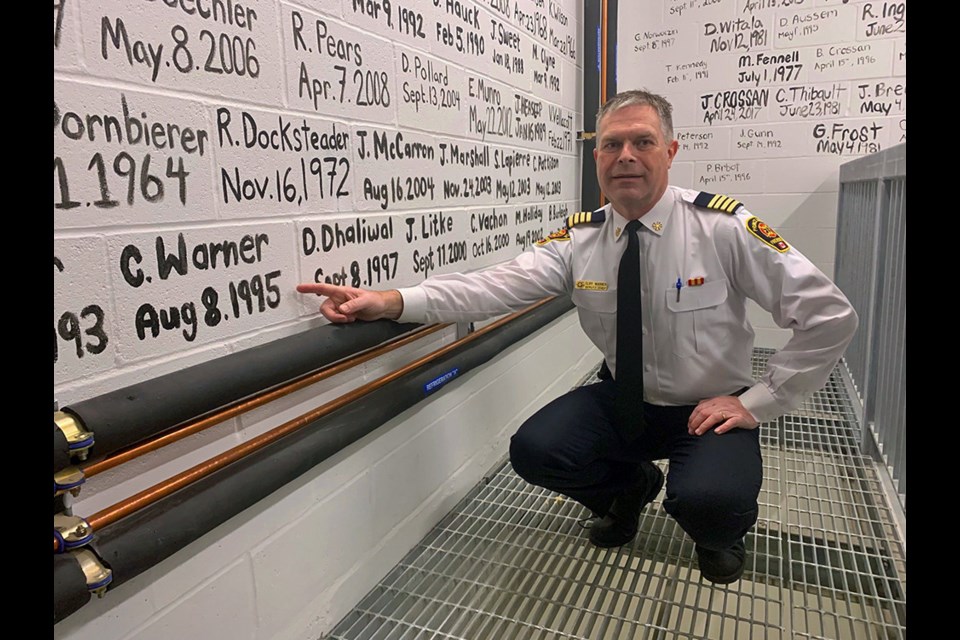

Much has changed in the three decades since Prince George fire chief Cliff Warner started his career, with the job now much safer for everyone involved in fighting a structure fire.

Firefighters still enter burning buildings without hesitation, hoses in hand, if they believe someone is inside. But the approach to tackling a fire is much different than when Warner first joined Prince George Fire Rescue.

“How we manage a fire now is exponentially better than it was, and that’s not a judgment on how things were managed when I started. It was what it was,” said Warner, who announced in January that he will retire on May 30.

“The biggest difference is that we’ve learned to manage the fire and take control of it. Sometimes people will wonder what we’re doing and it seems like it takes a long time to do something. But actually, through our strategies and tactics, we set up systems and processes to reduce risks to firefighters and improve the livable space for people who might be inside. Our members are much safer, and it provides a better opportunity for those who may be trapped.”

The nature of the job — being exposed to hazardous materials and the risks of injury from smoke, heat, and building collapses — makes firefighting a dangerous occupation. But Warner says firefighters no longer take the same risks they did 20 or 30 years ago.

“When I was a firefighter, we were crawling in, smoke down to the floor, your shins were burning, and you moved through, putting a fire out,” said Warner, 56. “Now, they set up ventilation, they control the path of the smoke and heat, and they work to push the smoke and heat out of the building, moving in behind it.

“The days of crawling into a door with smoke down to the floor — we just don’t do that anymore. We create a safe space, and the firefighter follows that safe space in and knocks the fire down. We’ve benefited from working with some real leaders in the province in fire suppression strategies and tactics.”

Looking back on his career, Warner says he’ll never forget the afternoon of April 16, 1997, when a natural gas explosion in downtown Quesnel levelled the Cariboo Closet thrift store and an adjacent trading card store. The blast, later attributed to shifting soil that ruptured the gas line, killed six people and injured 20. Warner was a dispatcher in Prince George at the time and had to co-ordinate the emergency response.

“It was just the magnitude of it,” he said. “Taking the information and dispatching multiple departments, monitoring and managing them on the radio system. I had never experienced something of that magnitude.”

Warner was one of the firefighters on duty May 26, 2008, when Canfor’s North Central Plywood mill was destroyed in a fire that spread to Interior Warehousing and piles of railway ties in a CN Rail storage area. While firefighters battled those blazes, a fourth fire broke out downtown at McInnis Lighting.

There was no fire truck available at the downtown hall to douse the blaze at the lighting store, and firefighters were forced to improvise.

“There was a crew of firefighters recovering from the NCP fire, and they ran down the street with hoses and a hydrant wrench and fought that fire at McInnis Lighting off a fire hydrant,” he said. “It was Armageddon.”

Warner was on a medical call at Fifth and Ospika when his crew was called back to the hall to respond with the ladder truck to NCP.

“I worked at NCP as a student for quite a few years on the cleanup crew, and it was an eerie, odd experience being there,” said Warner.

He was on the platform of the truck, watching a group of eight or 10 firefighters on the roof using a hose while they cut a trench through the roof of the mill to help the heat and smoke dissipate, when the situation suddenly deteriorated.

“That was a strategy back in the day to cut a trench, but we rarely go on the roofs now because you’re up above the fire in the most hazardous and dangerous area you can put anyone,” said Warner. “Something inside that mill let go, and there was a loud bang, and the fire spread across the whole place and actually came out of that hole the guys were trenching across. We had an air horn that was blasted, and everybody was ordered to evacuate.”

As bad as the fires were that day, no firefighters were injured.

Warner was 27 when he started with the fire department as a dispatcher in 1995. In his 30-year career, he’s run the gamut of fire department duties. He worked three years in dispatch, then spent the next 14 years on the fire crews. In 2011, he accepted a management role to take over the dispatch centre, serving in that capacity for three years before becoming deputy of administration and deputy of operations. He was appointed chief in January 2022.

When he first began dispatching 911 calls, computer technology at PGFR was in its infancy, and Warner relied on hand-held maps and binders to determine where to send the fire crews, with everything recorded on paper.

Now, with the switch to next-generation, internet-based 911 services, dispatch centres receive information from callers that more accurately pinpoint accident scenes. It also allows the public to send images or videos that help dispatchers make quick decisions about what resources to send.

PGFR, through the Regional District of Fraser-Fort George, provides 911 dispatch services for 100 fire departments in the region. When Warner first joined the force, there were just 26 departments under the Prince George dispatch centre’s umbrella.

In 2015, PGFR and its four fire halls received about 5,000 calls; last year, that number rose to nearly 11,000. More than half of all PGFR emergency dispatches are medical calls, and the numbers have skyrocketed with the ongoing opioid crisis.

In 2006, under former chief John Lane, Prince George became the first fire department in the province to require its firefighters to be trained to the level of emergency medical responder, the entry level for the BC Ambulance Service (BCAS). At least 10 PGFR members are also trained as primary care paramedics, and Warner says today’s firefighters are much more knowledgeable as medical first responders than when he was first hired.

“The skills of the EMR program have allowed us to become better at supporting individuals in the community who are having medical emergencies,” he said.

“I probably experienced a dozen overdoses in my 14-year firefighting career. Now, some of our firefighters do that in a four-day block. We’re trained to administer naloxone, and that was something added after I stopped being a firefighter.”

Warner said that, years before he started his career, Prince George firefighters did not respond to medical calls. But that changed when BCAS introduced advanced life support paramedic services to the city, and first responders were needed to support the expanded paramedic services.

“We’re an all-hazards department that operates in the city limits, and if someone calls for help, we go — we have no means to question why somebody is having their worst day,” said Warner. “We go, we assess, and we support as we can. It just happens that 56 to 58 per cent of those calls are medical-related.”

During Warner’s tenure, the city closed two homeless encampments, one near the courthouse and the other at Millennium Park. Warner ordered the Millennium camp to be dismantled because of its potential to trap people in a fire.

“There was one big fire there, and if that had gotten going at its peak (in the summer of 2023), it would have taken that whole block down in that segment of the park,” he said. “There was really only one way in and out of that place. It was not meeting any semblance of safety whatsoever, and I deemed that to be an extreme hazard to our members, to the people living there, and to the people in the area.”

Last year, the department retrofitted one of its pickup trucks to be used exclusively for medical calls, keeping the fire truck and crew at the fire hall, where they are better able to respond quickly to a fire call. The medic truck enhancement will go into service once PGFR has budget approval from city council to staff it with a WorkSafe-approved supervisor.

PGFR has about 100 firefighters, one of whom is Warner’s son, Matt. The city has budgeted $22.7 million for PGFR operations in 2025-26. Last year, it was $20 million.

The summer of 2024 saw the city working with BC Wildfire Services Prince George Fire Centre to host a wildfire summit, training 15 PGFR members in wildfire support and equipment use. City council approved funding for a specialized truck to be used in more rural areas to fight wildfires, and Warner says PGFR is taking a more active role in helping neighbouring communities with its structure protection trailer to keep wildfires in check.

“We understand and respect the budget challenges annually, and each year the budget numbers come out, they increase. We’re respectful of that, but we also understand it would have been easy to say, ‘We lost a subdivision, there should have been more done,’ so we put those (budget requests) forward,” said Warner.

Short of cutting down huge swaths of forest that border almost every Prince George community to make neighbourhoods safer, Warner says individual homeowners and business owners can do their part to reduce the likelihood of a wildfire disaster like Fort McMurray or Jasper.

“Go on the FireSmart BC website (https://firesmartbc.ca) and look at small things that can be done,” he said. “People have wood siding or cedar shakes, or they might have a cedar tree right up against the side of their building or a wood fence. In Fort McMurray, they found a house that caught fire and spread to a neighbouring house through a wood fence, so they put these chain-link fence breaks in to stop the spread.”

The wildfires in the Cariboo in 2017 weighed heavily on the PGFR dispatch centre and were the first real test of the city’s emergency management system when 10,000 people were suddenly evacuated to Prince George, forced out of their homes for weeks. Warner was the operations deputy at the time.

“The 911 calls from the Cariboo, reporting all those fires, were nonstop, and then it subsided. I went home for about half an hour, and Chief (John) Iverson called and said there could be as many as 20,000 people coming from 100 Mile and Williams Lake,” said Warner.

“The notion of evacuating a whole community was just not a thing. Our emergency program was built around protecting ourselves; there wasn’t anything built to say what to do to help other cities. Almost every year since then, we’ve supported communities evacuating. We’ve been a huge part of writing the provincial documentation on evacuation support for other communities moving to another area.”

The city has not yet announced who will replace Warner as chief.