Some nights, if she’s lucky, Brooke Molby still sees her brother in her dreams.

He visits her, from time to time.

In reality, she’s tucked neatly in her bed in Prince George, after a long day of work and a soccer game in the local rec league. But there are those special evenings when she closes her eyes and drifts to sleep, and there he is. Clear as day.

Most often, they’re in the front seat of his old, worn, green Acura, equipped with subwoofers so strong that her fingers would tingle when the bass dropped.

He knows every word to the Eminem song blaring through the after-stock speakers, and she laughs freely seeing him in his element.

But, without fail, Brooke Molby eventually wakes. She’s no longer in the old Acura. There is no 90’s rap music playing at a deafening volume. And, worst of all, she can’t pick up the phone, call her brother, and tell him about a dream that would surely make him laugh so hard his eyes clench closed with the same squinty, unbridled joy that all the Molbys seem to have when they smile.

She wishes she could, of course.

But Tyrell Jonathan Molby died on February 6th, 2019, from a lethal dose of fentanyl, two months shy of his 24th birthday.

When the school bell would sound, Brooke Molby knew exactly where to stand. Just outside her Grade 1 classroom, she would step aside as her classmates filed out, until her older brother Ty came to get her.

Without fail, he would arrive, take her hand, and guide her from the school all the way home, their hands locked together tightly. He was two years and nine months older than her; a lifetime in the eyes of a first grader. He was her protector.

Everyone who met him would proclaim him the sweetest. The most caring. The most compassionate. He’d stand up to bullies. He’d notice things that others his age didn’t; Tyrell would see a child in another grade who was without a friend and invite them to join him in whatever activity was happening that recess.

Everyone loved Ty Molby’s heart. Brooke loved Ty Molby’s heart.

But school bells didn’t represent all good things in their house. Mornings were a struggle. Brooke would be ready for school with her backpack on and shoes tied tightly, anticipating an exciting day of new discoveries and play time with friends.

For Ty, the school day was panic inducing. Some mornings, he would reject the idea of wearing shoes. He would flail on the floor and kick holes in the wall. He would melt down on the way to school, shaking in the car, screaming, and crying until he had developed a headache and his eyes were puffy with dread.

And that damn school bell.

When it would sound, signalling the start of the day, Ty’s meltdowns would start all over again. Even as a six-year-old, Brooke could see how hard it was for her mom, Sacha, to hand him over to the teachers as he flailed and cried out.

But his heart was rare. He would share his lunch with a kid in his class who didn’t have enough to eat. If a classmate was emotional, he was emotional.

And then, at 2:30, when the bell would sound, the “troubled kid in class,” would gather his bag, walk to the Grade 1 classroom door, and take the hand of the little sister who loved him so much.

By the time she was 12 years old, Brooke Molby was a bit of a soccer star. She was the best goalkeeper in town and seemed destined to play the game at a higher level.

Her brother’s love affair with the game was much less substantial. Ty had played one season, and after the league failed to hand out participation medals, he quit.

Unwaveringly principled, really.

Ty was almost never at her games. He couldn’t sit still enough to enjoy them. But he had great pride in the accomplishments of his baby sister. After games, he would sit next to her on the couch and, in a quiet moment, tell her she made him proud.

He’d then smile at her, and retreat to his bedroom where he had a guitar, a keyboard, and music producing equipment. He would shut the world out, often emotionally exhausted from a day in public, and create music for hours.

She was used to the sound coming from his room. He had no formal training, but you would have never known.

Brooke was a good student. Ty was better. He had started smoking marijuana as a way of coping with his anxiety and emotional distress, but it hadn’t stopped him from thriving academically. Straight A’s, report card after report card. But beyond the ten-out-of-ten marks on math tests and biology exams, Ty was fighting an uphill battle.

Despite his grades, he dropped out of school in Grade 10.

According to Google, the drive from Squamish to Prince George is supposed to be eight hours and 23 minutes long. What the internet hasn’t baked into its travel time estimate is the “my older brother is going through withdrawal, and we keep having to pull the car over” variable.

Brooke Molby had very little sympathy for her brother that day. She was en route to begin her university career, playing goalkeeper for the 2017 edition of the UNBC Timberwolves. But, along the way, Ty was sick.

His casual cannabis use was no longer working. Somewhere along the line, weed had turned to cocaine, and cocaine had become heroin.

Eventually, heroin wasn’t enough, and Ty began using crystal methamphetamine.

There was the time when he was walking home from a party, on drugs and alcohol, and he accidentally went into the house of a neighbour, not the Molbys’ home down the street.

Another time, Roy and Sacha Molby had been instructed to try the tough love approach with their son, so they kicked him out of the house. The hope was it would give him a reality check to clean up his act. Instead, he broke into the home, high, and smashed a giant window in the front of the house.

But, when real, clean Ty was around, it was special. He would suggest family movie night and make popcorn for everyone as they sat on the couch. Hearing the movie ended up being a struggle for Brooke, as her brother’s distinct laugh would ring out throughout the house. The Molbys would laugh at Ty’s laugh as much as he would laugh at the scene on the screen.

Despite the eight hour and 23 minute estimate being well short of her reality, Brooke was finally in Prince George. They had moved her bedding and clothes into UNBC’s residence, and she had met new teammates that would surely become lifelong friends.

She worried about her parents. She worried about her brother. But, sensing her nerves, Ty made sure to express to Brooke how proud he was that she was getting an education and playing soccer at the highest level of university sport in the country. He hadn’t even received a participation medal, after all.

Christmas 2018 felt different than the holiday one year prior. In 2017, back in Squamish after her first season in green and gold, Brooke couldn’t believe what she was seeing. Her parents were at wits’ end.

Roy and Sacha Molby had tried everything.

Massive fights were a regularity. Tears and tension were the usual. Tyrell’s good days were becoming fewer and farther between, and his family was wearing the effects.

Brooke had just completed her rookie season and had been tremendous as the Timberwolves’ starting keeper. But, on many days, her mind was back home. Now, seeing her family in a state of disarray made it quite clear; she had to quit soccer, drop out of UNBC, and return home.

She left her family with the intention of being back soon, thinking she could be of some help to the dire circumstances. But between her parents’ urging to stay at UNBC, and the support of Timberwolves coach Neil Sedgwick, Brooke remained a TWolf.

Now, in 2018, it felt like a completely different story. Ty’s eyes were clear.

So clear, and so twinkly, and so him. He had gotten worse before he got better, turning to fentanyl to deal with his intense emotions and mounting anxieties. But, there in the family living room in 2018, Ty was clean.

He was three months into a stay at a youth recovery centre, and Brooke could see the difference in her brother. She could feel the difference. For the first time in years, one good day was leading into another good day.

Part of the recovery process involved weekly calls. He would call his sister on Tuesdays. At first, she didn’t have much to say. Feelings were hurt. Frustration had been boiling for years. But he kept calling, and eventually the conversations became so beneficial that the recovery centre would allow Ty to stay on the line longer than the allowed time.

Seeing him for five days, clean and sober in the home they grew up in, was a glimpse into the future.

Kelowna, he decided was the right place to begin his new life. Squamish had too many bad memories for Ty. Too many connections to old acquaintances. Too easy access to dealers or other users.

Brooke Molby listened on the other end of the phone as her brother explained his plan. He was four months clean. That, alone, was a cause for celebration.

Roy and Sacha proudly picked their son up from recovery and made the trip to Kelowna with him. He had found a place to live. He had roommates, who he’d surely charm with his quick smile and dry wit. And best of all, he had a clear mind and new sense of purpose.

Ty knew recovery was a bubble. There were no triggers. The support was vast. But he was excited to get into a routine. Brooke would get a call every evening, around dinnertime, even though her brother knew that was a busy time to answer the phone.

Day one. Call.

Day two. Call.

Day three. Call.

Day four. Call.

Day five. Call.

Day six. No call.

Brooke called her brother that evening, but there was no answer. There was no return call.

The next morning, Brooke’s phone rang, and she answered it to the sound of her mom crying on the other end of the line.

Tyrell’s new roommates had found him in bed, dead from a lethal dose of fentanyl.

Next to him was a notepad with a to-do list.

Get groceries

Get cigarettes

Find online school, get GED

Find a Narcotics Anonymous group

Ty Molby was 23 years old. He had been clean for four months and six days.

Something shiny caught Brooke’s eye.

It was late 2022, and she was walking through a house with her parents. A realtor was showing them a ranching property in Beaverley; a small community just west of Prince George.

Her parents had long wanted to own a ranch, and the timing felt right. Whether this particular ranch was the right fit remained to be seen. As the real estate agent talked to Roy and Sacha about square footage or flooring, Brooke was distracted.

Wedged under the moulding where the wall meets the floor, was a dime. Ten cents worth of currency to most. A message from a loved one to Brooke and her family.

She scooped it up and put it in her pocket.

Three years had passed since Tyrell had died. The grief, some days, was too much to handle. The questions, endless.

It’s said that grief is the price we pay for love. It is also said that grief is not linear. The Molbys understood that all too well. One day, Brooke would be clear-minded and joyful, living with her roommates, attending university, and playing the game she loves.

Other days, the gaping hole in her heart rocked her to the core.

But the family started to notice dimes. Everywhere. Places where dimes would never, ever show up. Gardening? There was a dime, buried deep in the soil. Tucked in a book? A shiny dime. They soon realized these monetary surprises were messages. Notes of love from their smart, funny, musical, laughing, kind, compassionate boy.

When Brooke got in the car with her parents, she extended her palm and showed them what she had found in an otherwise-bare house.

The Molbys put in an offer for the ranch soon after.

A group of moms sits in a circle in the barn in Beaverly. They share a common grief. A familiar sadness.

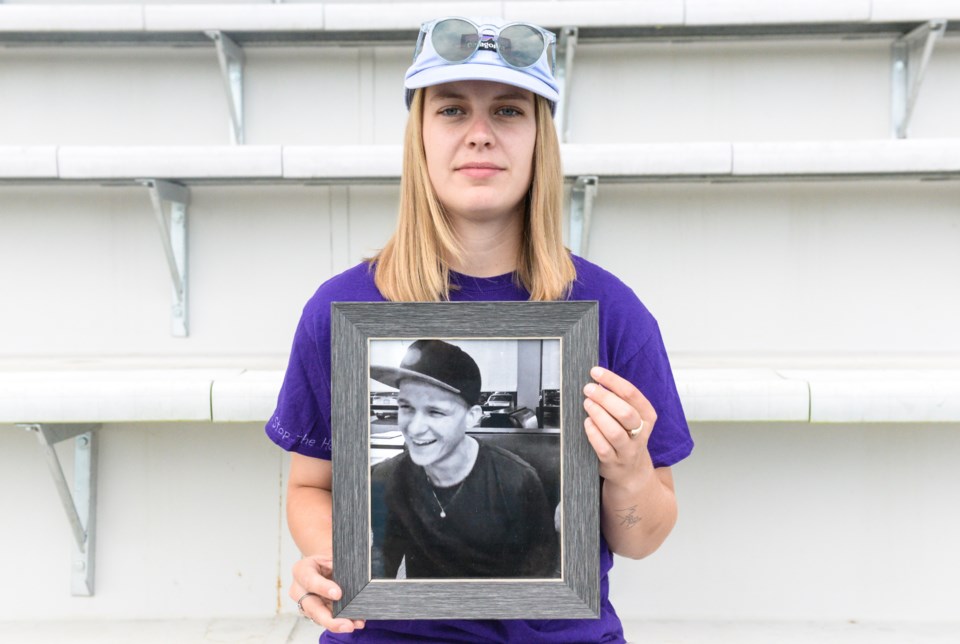

Healing Hearts is a branch of Moms Stop the Harm, a network of Canadian families impacted by substance-use-deaths. Sacha and Brooke Molby started the Prince George branch, recognizing the need for a support group in northern BC. They meet at the barn once a month.

The families sit and share about their loved ones, who share a common quality themselves. They were all human. They all had feelings and thoughts and plans. And, left behind, are the ones who knew that best.

There were 7328 apparent opioid toxicity deaths in Canada in 2022. An average of 20 deaths per day. Ty’s story is not unique. Every day, more sad stories added to the growing list. But each of them matters. The stigma is what must be lost in the process of understanding.

Brooke sits in the group and thinks about what could have been for her brother. He should have worked with people. He would have been a wonderful, doting father. Her plan is talk about him as much as possible. To keep him alive with her stories, and remind everyone that people are not statistics, but as human as they are.

As the group departs, she walks by the giant sign at the perimeter of the property.

“Lucky Dime Stables.”

Brooke Molby cries about her brother, some days. She will get in the car, turn up the music, and smile through her tears when a song her brother loved comes through the speakers.

Today, she plays a song Tyrell knew every word to. “Ashes” by Snak the Ripper.

“That's the last time that we spoke on the phone

I know that you're gone

But I hope that you know

You've taught me some shit that I’ll never let go

You're a part of me now and I hope that it shows

Every time that I happen to see my reflection

It's you staring back from the other direction.”