Nearly half of local Indigenous students aren’t completing high school in the normal five years, according to a report by School District 57 superintendent Cindy Heitman.

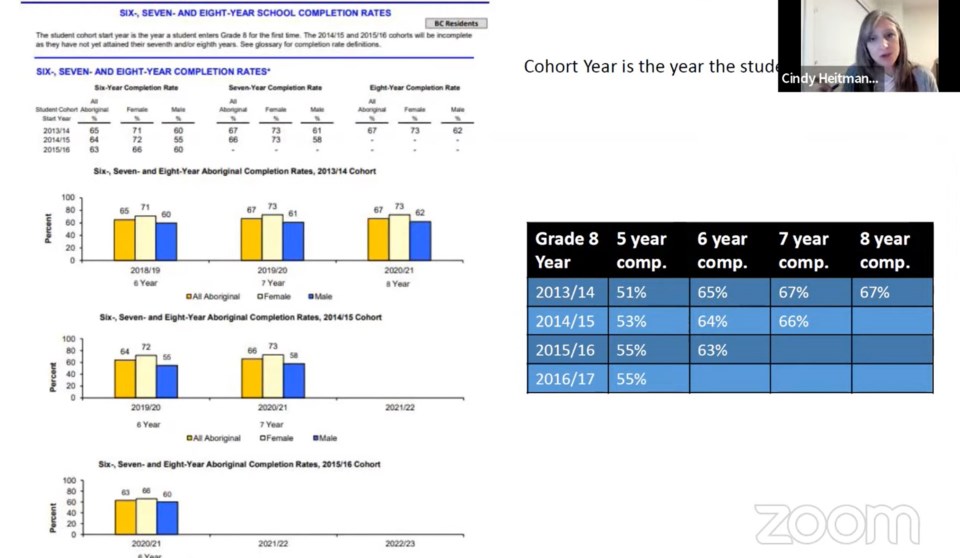

Only 51 per cent of Indigenous students who started Grade 8 in the 2013/14 school year graduated in the 2017/18 school year, Heitman said during a report to the district board of education on Tuesday. By the 2020/21 school year, only 67 per cent of those students had graduated.

Indigenous students who started Grade 8 in the 2014/15, 2015/16 and 2016/17 had similar five-year completion rates, ranging from 53 per cent to 55 per cent, she said.

Based on survey information, students who feel connected and welcome at school stay and graduate, Heitman said.

“We lose kids early on in high schools,” Heitman said. “Our kids don’t feel like they belong, they don’t feel like they’re connected. We know that we retain those kids to Grade 11 and then… where we see the drop is (Grade) 11 to 12.”

One of the things Heitman said the district intends to do is look at how the elementary school experience is preparing Indigenous students for high school.

“One out of two is a staggering number,” trustee Tim Bennett said.

He asked the district administration to look at how different high schools throughout the district prepare Grade 8 students, to look for best practices.

Board chairperson Sharel Warrington said the problems are systemic across B.C. and Canada, “it’s not just Prince George.”

“There are more questions than answers, when we look at the data,” she said. “When we look at the survey results… a large percentage of students are saying that they are not getting what they need to be prepared for the future.”

In some cases half or even 60 to 70 per cent of students are staying they are not getting what they need in school to be ready for the future, she said.

Trustee Rachael Weber said she’s disappointed that Indigenous students are still being required to self-identify every year. In some cases, students who have self-identified in one year have not in following years, Heitman told the board.

“Why are we living in a colonial system where we are asking them to identify who they are every year?” Weber said. “McLeod Lake Indian Band raised this issue two years ago, and it is still going on.”

Trustee Milton Mahoney said that students dropping out in Grade 11 may not just be about what is happening in school, but what is happening in that student’s life outside of school.

“Are people dropping out to work, to help support the family? It’s not just a case of people coming to Grade 12 and saying, ‘Nah, that’s it,’” Mahoney said.

‘A SIGNAL OF WORKING TOGETHER’

On Feb. 15, members of the School District 57 board of education and senior administration met with the Indigenous Education Leadership Table, formed by a partnership between the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation and McLeod Lake Indian Band.

“It was a signal of working together,” Heitman said. “Our experience was, we listened. We heard frustration over the harm that has been done. We learned about self-determination and governance. This is a situation that is new. We are looking forward to the opportunity to work alongside (the leadership table) to make things better.”

Warrington said the biggest take-away from the meeting was the desire to get to work to improve outcome for indigenous students.

“We were able to acknowledge the voice of McLeod Lake Indian Band and Lheidli T’enneh,” Warrington said. “We all came away with open hearts and open minds, and that we are working toward that better path.”