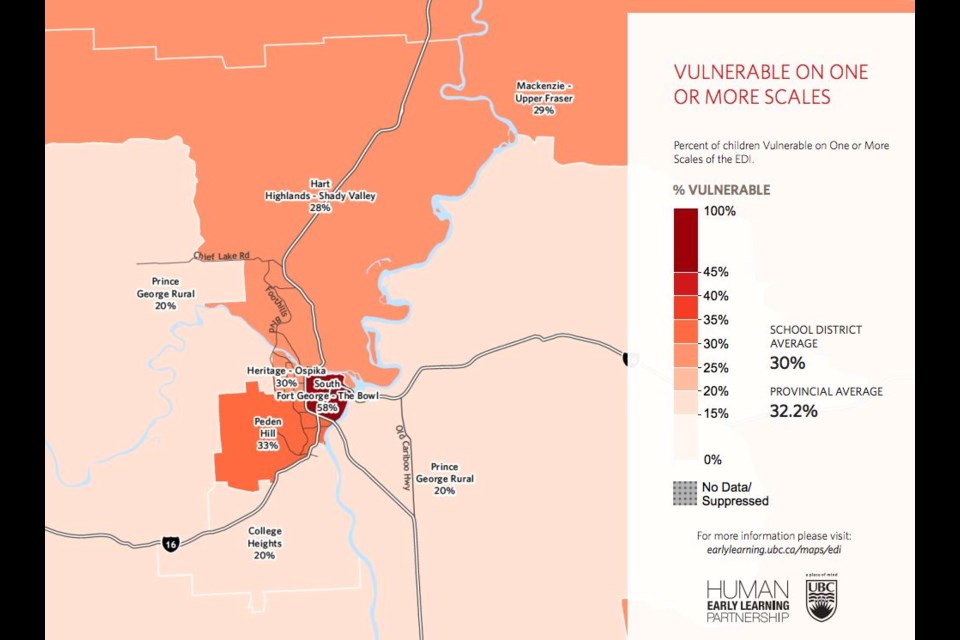

Nearly a third of children starting school in School District 57 are considered vulnerable, with the numbers jumping to 58 per cent in some parts of Prince George, according to a report by the Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP).

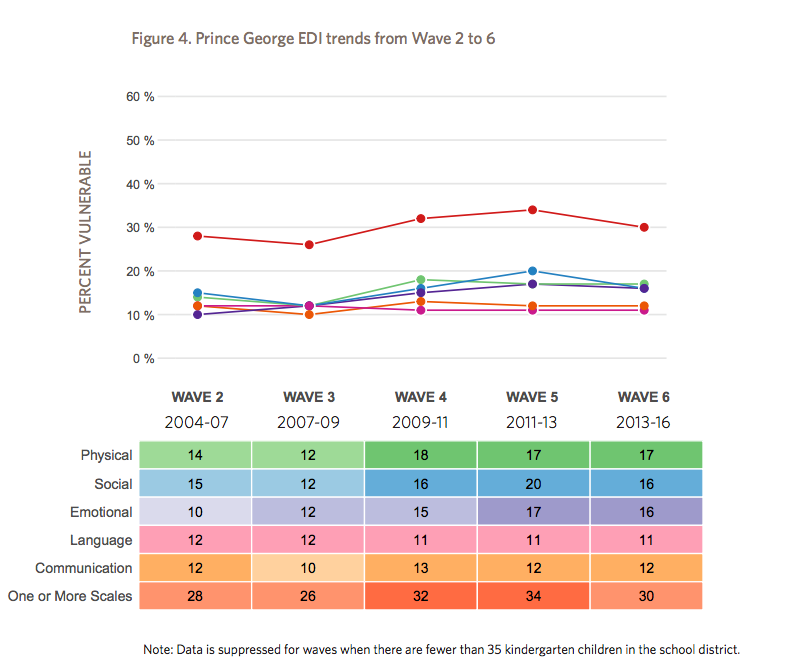

The interdisciplinary research team, based at the University of B.C., reported that overall 30 per cent of students were considered vulnerable in School District 57, just slightly better than the provincial average of 32 per cent - based on children studied between 2013 and 2016.

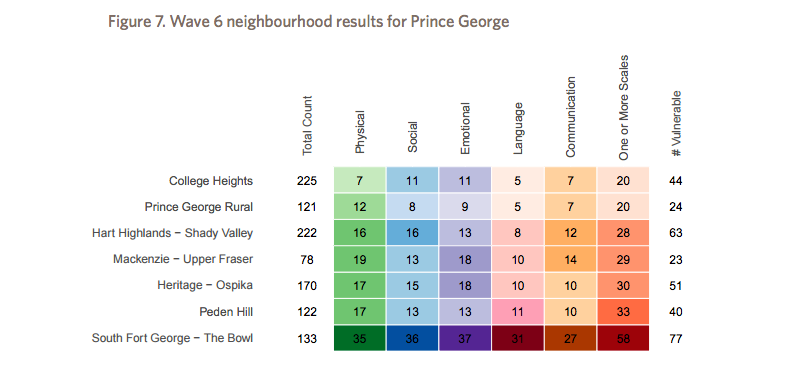

The data drills into child health by neighbourhood, looking at how students do in five categories - physical health and wellbeing, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive development, and communication skills and general knowledge - the latest results from a survey that has been measuring province-wide patterns in children's developmental health since 2001.

The school district's most vulnerable neighbourhoods are South Fort George-the Bowl, with 58 per cent of children performing poorly on one of those scales, Peden Hill with 33 per cent, followed by Heritage-Ospika with 30 per cent.

College Heights and rural Prince George were both on the lower end, with 20 per cent considered vulnerable, according to the report published this week.

The report also highlighted Hart Highlands, on the lower end with 28 per cent vulnerable, but it showed a 10 per cent jump in vulnerability compared to the previous reporting period.

The north's performance reflects what Northern Health's Chief Medical Health Office Dr. Sandra Allison found in her April 2016 child health report looking at the region.

"It certainly does support the concerns I have around school readiness," said Allison, whose work look at data pulled from the previous Early Development Instrument (EDI) survey between 2011 and 2013.

"We probably will need to increase our resources at school to assist our teachers to either improve those student skills or help them cope in an environment in which they're not ready. You might see behaviour issues, you might see issues in schools related to a failure to succeed or their not embracing the environment or the materials as well as they should because they're not ready."

Poverty plays a huge role, said Dr. Martin Guhn, an assistant professor at UBC, who works with HELP. In School District 57, most of the data was collected last school year - from 1,019 kids out of 12,147 enrolled - with a couple dozen more studied the year before and this school year. The district did not respond to requests for an interview.

"If you don't have any resources then it affects nutrition, it affects access to play opportunities, it affects how much time the parents have because they often work more hours to get out of poverty," said Guhn, adding it's important to look at specific barriers certain areas face - like transportation or food security or language and culture.

The gaps from region to region and neighbourhood to neighbourhood showcase the inequality that exist in each community.

"The question is what can be done to create more equity in our society? We're hoping that we can over time shine light on the success stories so that others can learn from it," he said. "It takes a long time, it takes collaboration, it takes access to resources and decision making."

Northern Health's children's first manager Sandra Saski would like to see children assessed as early as three years old. As it stands, children see a health nurse at 18 months and then in kindergarten at five.

"It's that gap that we find children's delays are getting missed," she said, adding more could be done if the problems were identified sooner. "That's what we're working on. It's not a simple fix. Smaller rural places have been able to do it a little easier. Prince George is big therefore it's more difficult to navigate."

The numbers are no surprise to the many agencies who sit on the city's Children Youth and Family Network, Saski said, adding it's already doing "lots of good work" to try and address the overall health and the gaps felt most harshly in the bowl.

Having regular neighbourhood-specific data is important for the group's ongoing work said the city's manager of social development Chris Bone, who also works with the network.

"No one sector in the community can unilaterally improve those scores. It's not just the school's responsibility, it's not just the City of Prince George's or the social service agencies. It's the community as a whole," said Bone, who said the city can likely have the most impact on physical health.

In early October, before the select standing committee on finance, the Prince George Child Development Centre called for more money to support its struggling services, pointing to the EDI indicators as proof that the status quo isn't working.

"The failure of the province to make meaningful, or any, improvement in this area has to do with resourcing," said its executive director Darrell Roze.

While literacy and numeracy is improving in B.C., Guhn said social and emotional issues have worsened.

"It's not a local phenomenon," Guhn said. "The question again is are we looking carefully at what we've changed in the social environment conditions over the past generation, how that's affecting our children.... "That's the question we have to collectively ask ourselves: is that the direction we want to go in?"

Allison called for more investment in children, adding unhealthy children can lead to mental health issues and chronic disease later in life.

"A lot of this can be prevented with appropriate investments and understanding that we might need to make sacrifices to make the outcome improve," she said.

"That's a challenge because that comes down to money and budget."

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)