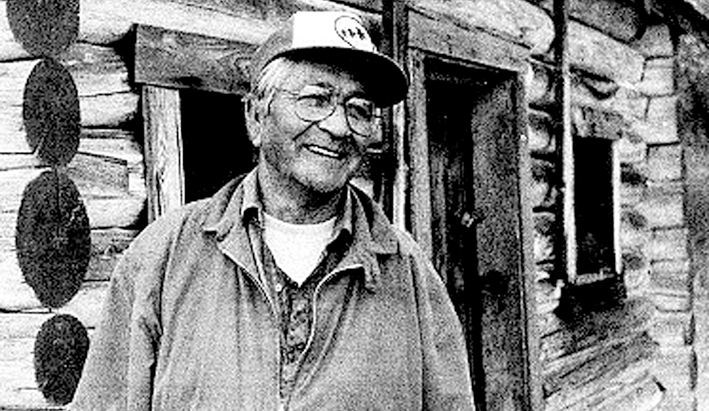

One of the area's leading political and cultural figures, Harry Chingee, has passed away at the age of almost 96 years.

Chingee spent decades as an elected councillor for the McLeod Lake First Nation, much of that time as chief. Today, the MLFN is considered by many to be a national model for holding fast to his community's traditions while also fully participating in the natural resources economy.

"Harry will be sorely missed for his kindness, smile and warmth, but his teachings will not soon be forgotten," said a statement issued by his loved ones.

"He left us on Sept. 21, 2018 in the same graceful and gentle loving way that we've all come to know of him."

Chingee used his traditional upbringing to great affect in his life. He was a professional hunting guide, using his intimate knowledge of the land plus the lessons passed down to him from his elder generations.

"When he and his wife, Patricia, were raising their 13 children at McLeod Lake, Harry's skill as a hunter provided most of the family's meat," said Citizen reporter and local author Bev Christensen, writing about Chingee in 1989 in the Oct. 21 edition of Plus Magazine.

She told the story of two grizzly bear encounters he remembered well.

"I was hunting back up in the hills, hunting moose at about this time of the year," he said. "I saw moose tracks but never saw or heard anything. I was walking around when I heard something behind me and there was an 800- or 900-pound grizzly coming right at me so I dropped my gun and pumped a shot into him and he dropped seven or eight feet from me."

He admits he was lucky to hit the animal in the head because, if he'd hit it anywhere else, it could have killed Chingee with one swipe of his paw before it died, Christensen said.

Another time a grizzly rose up in front of him then dropped down on all fours and charged. Again he dropped it with one shot.

Chingee first became chief of the MLFN in 1950s, holding the position again in the '60s and '70s. It combined his instinctual passion for the outdoor traditional lifestyle with decision-making on behalf of future generations.

Not all members of the McLeod Lake Indian Band are hunters, he explained to Christensen, telling her some have "become 'Safeway hunters' because then they know they'll get something to eat." Chingee worried that "these young natives have 'lost track' of traditional hunting skills. Some are getting back to it but they need help."

Chingee was not shy about taking strong stands on behalf of his constituents. He participated in more than one blockade of industrial activity on McLeod Lake territory.

Those blockades were part of the learning done by the provincial government and private industry that is commonplace today to include First Nations in any business done on the land.

He led by example. He and his apprentice guides (including some of his children) would take high-paying foreign hunters into the remote mountains of the region, then use the meat (foreign tourists are ineligible from taking the meat for themselves) for the benefit of the band members, using every last morsel including the nose, then also tan the hides of the game they took for making commercial leather items.

Chingee also presided over an agreement by a pulp mill operating on McLeod Lake territory to hire a set percentage of his band members as a condition of working on their then-unceded lands.

As a forest industry worker as well (he was a forestry technician by certification, and also did logging jobs), he extended that enterprise to include the formation of a logging company (it has grown to include a construction division as well, today) to carry out forestry operations on McLeod Lake's landscape and partner with other proponents of industrial projects.

"I think the biggest problem we have is that our people can't get work. That's why we want to get control of our own resources," Chingee told Citizen reporter Gordon Clark in 1987 when he led a blockade of Carp Lake Provincial Park in answer to logging going on without permission on a nearby parcel of McLeod Lake's land.

"All they want," he said of the protesters, "is the chance to work like the rest of the people in Canada. White society is racist (by making it) difficult for native people to find work. You remember the recession? It was hard on whites, but it was 10 times harder (on Aboriginal people because First Nations workers are) the first to go when the times get tough. It's hopeless for us until we can get something going on our own."

That they did. When Chingee stopped being chief in 1997 (after a 23-year run of consecutive years in elected office), the movement was well underway to bring McLeod Lake into the Treaty 8 agreement (that was ratified in 2000), they were operating a number of successful businesses in mutual partnership with the private sector and other forms of government, and his personal family had grown widely.

Family was fundamentally important to him, since he was forced out of his parents' home when Aboriginal children were wrested from their homes on punishment of arrest during the residential school sweeps of his era.

He spent a number of years at Lejac Residential School but no official records of his attendance survived to the modern age so Chingee was forced to go through a protracted legal process to obtain the standard compensation owed to all victims of the residential school atrocity.

Chingee was predeceased by his wife Patricia, daughters Florence, Molly, Caroline, Bernadette and Jackie. He is survived and remembered by his daughters Sheila and Anna, sons Victor, Gilbert, Ralph, Lester, Bernard, Harley and Charles plus numerous grandchildren.

Some of them have taken up Harry Chingee's place at the council table.