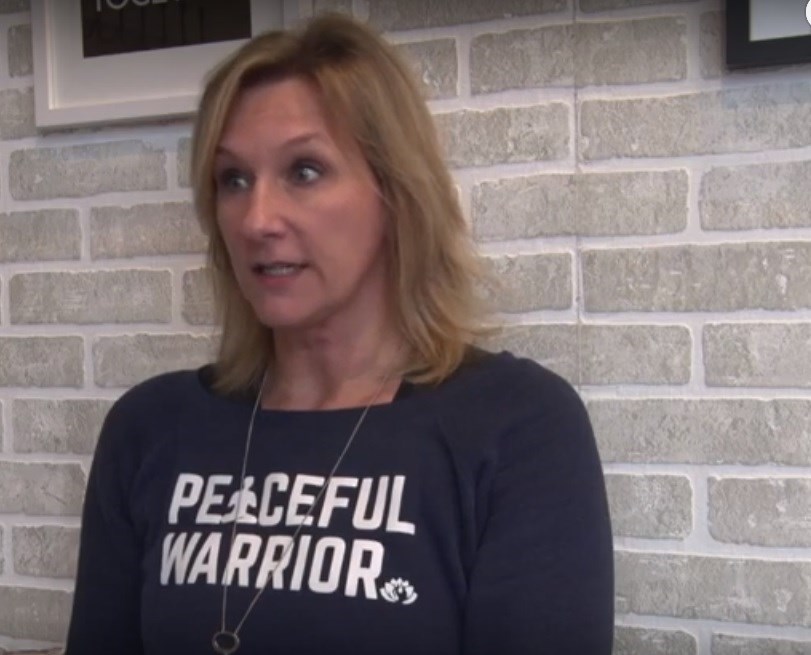

Following a recent Castanet series on the lack of addiction services in Kelowna, mom Pam Rader shares what it’s like to be living that reality right now with her 26-year-old son’s addiction problem.

Rader’s son started showing signs of addiction in his teenage years with alcohol. By 18, he was doing oxycontin and then moved into heroin.

It’s been more than a decade of the family dealing with the system, says Rader. It’s shown her how slow-moving and overly-bureaucratic the process of getting into a treatment facility can be.

“In the past, it was so much easier to get him into treatment because it was based on self-referral. ... If I was not in a position to help my son, he would be dead now, because of the current barriers that Interior Health has imposed on people suffering from mental health, trauma and addiction.”

Interior Health’s process required him to attend a doctor’s appointment, a nurse’s appointment, and three community substance-use meetings on specific dates and times. At one of these meetings, he was offered heroin by another participant and ended up relapsing again.

After that, a one- to three-month wait was required before he could see an alcohol and drug counsellor, who could choose to fill out a referral package. From there, it could be several months before he finds out whether he will get a treatment bed.

"These kids don’t have that long — they're going to die,” says Rader.

"We have a small window when people actually want to get treatment when it can help them, and we need to make stuff happen really quickly. We need to have a system that when that window occurs there is swift and rapid access to treatment. It’s cheaper than jail, it’s cheaper than putting them through the court system, it’s cheaper than policing downtown, and it’s certainly cheaper than a funeral."

Rader says she understands the importance of the addict making their own decision to get well, as her son has done on multiple occasions, but that facilities need to be significantly more accessible if there is any possibility of ending the crisis.

"At no time in the past decade has it been more barriers to get treatment than it is, so whatever it is they’re saying they’re doing, I’m not seeing it, and my son’s not seeing it. We drove my son to Vancouver in a snowstorm one day just to get a referral done. My husband took a day off work, I took a day off work, we drove him down and back in a day to get that done. But if somebody doesn’t have someone to do that for them, they’re never getting treatment. Even with the referral package done, it could still be a tremendous wait for him to get in there.

"As a parent, I have to sit with this every day and know this is real — that I could lose my son because the government won’t fund another bed. I can’t even fathom that."

— Laura Brookes, Castanet