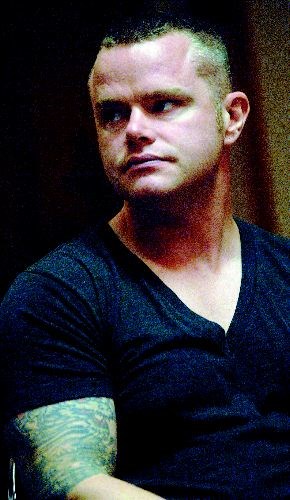

Jason Coulter didn't even know he was in a gang until his group of friends were getting headlines. He sure knew it was a gang when the cops were tracking their every move, when rival gangs were gunning for them, and when he made to leave.

Coulter exited the gang life by leaving the country (almost the hemisphere) to distance himself from the life he was leading. He is back now, but he lost everything he had as a member of the UN Gang, one of the nation's most violent and notorious organized crime factions. He is proud to be rid of it.

"I went from driving a $100,000 car to taking public transportation because I had no driver's license," he told a Prince George audience at the Community Solutions-Gang Crime Summit on Monday and Tuesday.

He lost the big, fast money but he also lost the crack addiction. He shed the manic freak-outs when he stalked his own house alone, armed with guns and swords, thinking the wind in the trees outside were authorities coming to get him. He lost the target on his back, but he also lost a lot of friends.

Coulter is the first to admit he isn't the typical gangster story in B.C. He didn't get hazed into the gang with a ceremonial beating, he didn't leave in a hail of bullets; his gang didn't operate that way at the time. He was out before the UN became, like several gangs in the Lower Mainland, a tool of grotesque violence - but not before the drugs and the violence were taking their toll.

"I smoked crack every day for six months," he said. "I lost my marriage, I lost my house, I almost lost my mind." His friends had to chain him to a pole for weeks to detoxify him.

He headed for Central America to be a real estate agent, but it was on the proviso he have zero contact with the old gang contacts.

While in the impoverished Third World he witnessed addiction at a whole other level than he ever did in Vancouver. "Crack was cheaper than eating," he said, and small children he knew were sucking on the cocaine tit. What was already in his mind became a total change of heart. He wanted to spare lives from the effects of drugs. He wanted to go home.

He is now one of the starkest living mentors the Lower Mainland has in the fight against addiction, poverty, and dysfunction. He counsels youth, he counsels men, he counsels the homeless, and he is an open book for the province to read about what life inside the gang epidemic really feels like.

"I was going to buy a castle in Mexico and retire there," he said, describing his mentality getting into the drug trade. "I was going to make as much money as possible as fast as possible and then get out. It was a naive thought. When you're young, you think you know it all."

Coulter doesn't think it's possible to eradicate gangs, he said, but don't worry about that. "You can stomp out a lot of it," he said, and considers the Lower Mainland a big success story despite the rate of violence there still. It is turning around.

At a funeral for one of their fallen co-members, the UN posed for a group portrait. There were 60 faces in the picture, including Coulter in the front row with the rest of the original founders. Half of those people are now either dead or in jail. Showing kids in school the graphic truth about where gang life and drug life will take them might be a technique that keeps some of them away from that life, he said. He remembers being scared of AIDS in Grade 8 because of the sex education presentations back then.

Each gang member has a personal story of trauma, he surmised. For himself "I have abandonment issues" due to a mother and father both addicted to the point he was in foster care by six months of age. Between the ages of 12 and 15 he lived in 20 different foster locations.

To exit the gang was only one part, perhaps the easiest part. After that he had to deal with the root demons of his background. He took courses and spiritual healing sessions so much so that he now teaches some of it to others, especially grieving techniques.

"I've had a lot of friends die," he said. "The real truth of gangs...there is a lot of stress, you are always looking over your shoulder, when you're called you have to come, and there is a lot of death."