Residents of B.C. can always find something instantly recognizable in the paintings of E.J. Hughes, from totem poles at Stanley Park to arbutus trees at a Crofton beach. But the familiar content of his paintings is not specifically what made his output so impressive.

One of the most famous painters ever to call Vancouver Island home, Hughes was a true master of “observational realism” — a catch-all term Robert Amos, his official biographer, created after trying in vain to find more rational ways of explaining Hughes’s abilities.

“He had an extraordinary, almost Zen-like ability to concentrate, to pay attention to what is exactly in front of him,” said Amos, a columnist who covered the Victoria art scene for the Times Colonist for more than 30 years.

“It could be a pebble on a beach, or a weathered plank, or a leaf on some insignificant roadside weed. All of it is treated with pure, loving attention. And it never varied.”

E.J. Hughes Paints British Columbia is a new book from Amos which chronicles Hughes’s work through examples of more than 200 watercolours, oil paintings, drawings, and engravings. Amos has been building a catalogue raisonné of Hughes’s work since 2010, when he was asked by Pat Salmon, who worked closely with Hughes for 30 years, to become Hughes’s biographer.

Amos agreed, and with the blessing of Hughes’s estate, has now written two retrospectives of the artist’s work. The first, E.J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island, was a finalist for the City of Victoria Butler Book Prize and the B.C. Book Prize, and spent 43 consecutive weeks on the B.C. Bestsellers list, on its way to becoming one of the top-selling books in B.C. in 2018.

E.J. Hughes Paints British Columbia, released Nov. 5, has the makings of another fan favourite. The book features work from every facet of a career that saw the Vancouver native, who moved to Victoria to live with his parents in 1946, reach lofty heights in the Canadian art world.

His were humble beginnings, Amos said, but his talent was evident early. When he was a student at the Vancouver School of Applied Art and Design between 1929 and 1935, Hughes became known as one of the premier young artists in the province.

“He was preternaturally talented from the start. Even as a 15 year old, he was creating paintings in watercolour of incredible proficiency.”

Hughes lived in Shawnigan Lake until 1974 and called Duncan home until his death in 2007 at the age of 93. His popularity has grown considerably in recent years, with a number of his paintings fetching record amounts from collectors. Fishboats, Rivers Inlet, his first painting after moving to Victoria in the late 1940s, sold for $2 million at auction in 2018, the highest total paid for a Hughes original to date.

Amos marveled at the breadth of Hughes’s catalogue when he first came across it. Specific works were drawn and painted several times, never technically being finished in Hughes’s eyes. He would often come back to earlier works, such as the picture he drew of Savary Island in 1938, which he painted in oil in 1953 and in watercolour in 2006. The iconic artist never based any of his paintings on photographs he’d taken, which is how the majority of artists work today.

“That is a really rare commodity these days. You rarely find people who are actually drawing what is in front of them, but that was Hughes’s process. He would sit for an unconscionable amount of time, typically two days, sitting in front of a subject and drawing it with a pencil. On the third day, he’s annotate the drawings, with notes to himself of the colours and tones he was going to use. Those drawings are the basis for the fully realized oil paintings which resulted.”

Hughes took a trip from Victoria to Courtney in 1948, stopping over the course of a week in communities along the way, including Ladysmith, Nanaimo, Qualicum Beach and Courtenay. Some of these painting are what appear in E.J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island, Amos said. “From there, he went out and made drawings that became the foundation of his life’s work as a painter of Vancouver Island.”

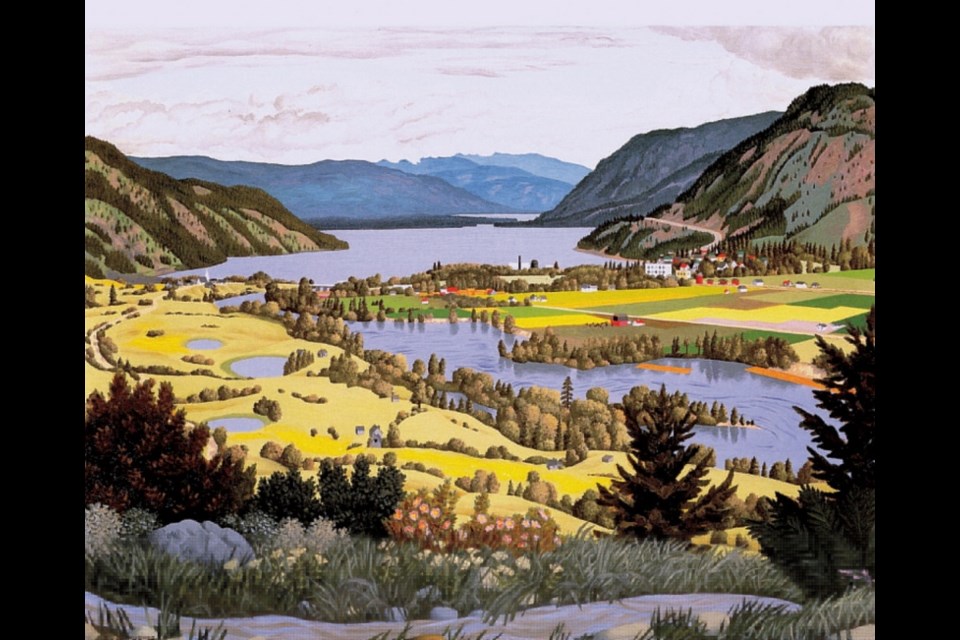

A very private man, Hughes ne never left the Island for work after 1967, according to Amos, but he would occasionally cast his gaze off-Island earlier in his career. One seminal trip took him along the coast of British Columbia and through parts of the mainland, resulting in paitings that now fills the pages of E.J. Hughes Paints British Columbia.

Amos recently traveled to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa to see some of Hughes’s work as a war painter, the majority of which has never been displayed publicly. Hughes was the first Canadian war artist of World War II, and the longest-serving. His productivity was immense during that time: More than 650 pieces of art Hughes created during that time now reside in the Canadian War Museum, and will form the backbone of Amos’s next Hughes biography.

“Although we know him as a highly detailed and resolved painter, the work that he did during the war takes that resolution to a much high magnification. It’s an astonishing performance.”

An excerpt from E.J. Hughes Paints British Columbia by Robert Amos

The fourth of Hughes’s dark postwar paintings, Indian Church, North Vancouver (1947), involved more extensive preparation than any other Hughes image.

For some time, while he was a student at the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts (1929–35), Hughes lived with his mother’s older brothers, the “McLean uncles,” at 243 6th Street West in North Vancouver. Nearby is St. Paul’s Church, a western mission of a Catholic religious order, the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. This tall wooden building, with its distinctive twin spires, was built near the shore of Burrard Inlet in North Vancouver in 1909–10.

Previously, the Coast Salish peoples and Portuguese settlers had lived at what came to be Stanley Park. When the Hastings Mill on Burrard Inlet came into operation, the new colonial government decided to expropriate those residents and transform their homes into a civic park. Uprooted from desirable sites, they were moved across the harbour to a place called Ustlawn.

Father Leon Fouquet built a small church at Ustlawn in 1866, and a larger one called St. Paul’s on the same spot several years later. In 1869 the colonial authorities set aside Ustlawn for the Squamish people and called it Mission Indian Reserve Number One.

Almost next door to St. Paul’s Church was the home of Emily Carr’s friend, the basket maker Sophie Frank. Carr visited her there a number of times, even during the years when Hughes lived nearby. Susan Crean wrote about the relationship of Sophie Frank and Emily in her book The Laughing One: “[Carr] had formed a friendship with a Squamish woman named Sophie Frank, whom she met in 1906 when she moved to Vancouver.

They visited back and forth, Emily taking the motor launch across Burrard Inlet to visit Sophie on the North Vancouver reserve where the two of them would drink tea and tell stories. From the time they met, Emily felt a special attachment to Sophie, and they remained friends until Sophie’s death in 1939.”

Hughes’s first pencil note of the shoreline and St. Paul’s Church is tentatively dated 1933. Children play near the tidewater, and the twin spires of the church are reflected in the pools below. Back from the water, Hughes drew a couple of canoe sheds and, beyond the church, a row of wooden houses. A single telephone pole adds a modern touch and anchors the composition on the right of the church.

Hughes was clearly fascinated by St. Paul’s Church in North Vancouver, creating a number of drawings and paintings of the building from different angles. The extensive annotations on an early watercolour of the church, Indian Church, North Vancouver, BC (1939), indicate that Hughes had plans for the image, and through a number of drawings and prints he continued to develop it.

Each time he returned to this subject, he refined and dramatized the scene. At one point it had a railroad track, but then he drew a meandering shoreline and a dugout canoe at the water’s edge. Among the people on the boardwalk, a man heads home with his oars over his shoulder. This beautiful watercolour has been squared off for enlargement for eventual production as a linocut, and though two prints of the black-printed key block are known, no colour print of this design was ever produced.

Hughes again took up the image of St. Paul’s Church in 1947, after his return from the war. This was the fourth of his postwar paintings, and he was determined to make it an outstanding picture. In preparation, he created a small tonal study in watercolour that, though tiny, he believed could be seen across the room. He had seen his work exhibited in various exhibitions with official Canadian War Artists, often with poor lighting in dim drill halls.

Now, to make his paintings ring out, he decided that he needed to simplify his subject matter and put it across with a strong compositional kick. With that in mind, he did this little study to bring a different expression to what had been a gentle picture of St. Paul’s Church in North Vancouver.

Without the prospect of likely customers or exhibitions ahead of him, Hughes took out one of the large canvases he had brought home from the War Art Program and set to work. The painting of St. Paul’s is one of the largest Hughes ever made, at forty by forty-eight inches (101.6 x 122.0 cm).

In the new image, the fronts of the church and the houses shine with an intense light from the south, set against a brooding sky of tumultuous and profound darkness. The North Shore Mountains now seem to rise to awesome heights.

“There is an element of menace in the image,” Ian Thom wrote in his book on Hughes, “heightened by the minute scale of the people. The houses are monstrously large, and the church, in contrast to everything around it, is nobly erect.”

Hughes himself didn’t think of the scene as menacing at all, but full of dignity. Pat Salmon quoted him as saying, “I saw dignity in the sight of the old church rising above the humble houses nearby. I cut out a lot of the ornament and detail of the steeples.

I almost made them unreal in attempting to simplify it.” In the foreground, children are going about their activities, there are people sitting on the boardwalk, and smoke rises from a distant chimney. Despite its darkness, this painting shows a world at peace.

- Mike Delvin, Times Colonist