Before the pain in her knee started, Christina Conrad was like any other kid in a northern B.C. town. She played in the forest near her parent's large Fort Nelson property, she biked with her brother, she lived an active life.

But at age 11, the growing bump became a debilitating condition, one that kept her from playing with the carefree physicality of her friends.

Years later Conrad, now 25, learned Osgood-Schlatter disease - or jumper's knee - could be treated by a physiotherapist. But that was never an option in Fort Nelson, and access to that service still isn't a reality in her hometown and many other rural communities.

"My knee's really minor in comparison to a lot of what people (face) but if something that minor could have impacted my life in a big way it makes me think about people who have bigger issues and injuries," said Conrad, who - after getting treatment - dropped several pant sizes, started biking and completed a triathlon pain-free last year.

Nine northern towns don't have physiotherapy and as many as eight have unfilled positions, though Northern Health only has postings for six positions across the region.

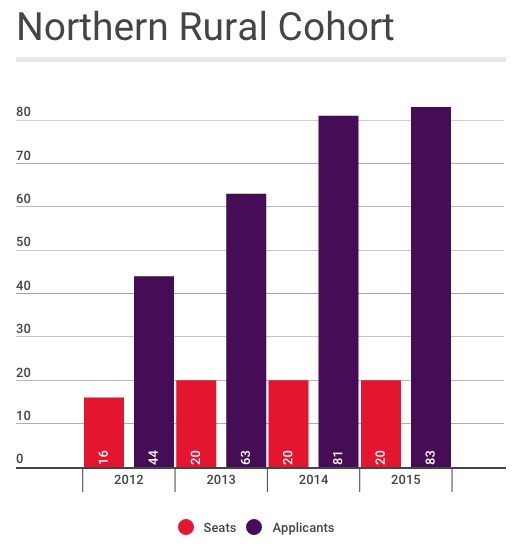

That gap in services inspired Conrad to pursue the profession. She specified on her University of British Columbia application she wanted one of the 20 spots in its northern rural cohort, established in 2012.

"That's why I'm here," she said. "Physiotherapy changed my life and I thought, that's not fair."

Conrad is among this year's graduating class. Last summer, she was in Prince George doing a placement at the Central Interior Native Health Society. This week, she returned to Prince George for her final placement at the University Hospital of Northern B.C., where she has been hired to stay.

She's an example of what some of the early data indicates. Those trained in the rural and northern communities are more likely to choose those locations. The first class of 16, which graduated in 2014, showed half chose positions out of urban centres. Only two of those were in the north. Over three weeks the cohort students learn via video conference at UNBC and pick four of six placement in rural towns. While each of the six students The Citizen spoke with was considering rural practice, some of the first-year students said choosing that route can be difficult.

The availability of mentors and upgrading opportunities were just two barriers.

"Especially right after graduating I think a lot of people want to live in the bigger centres because that's where they can take courses more easily," said Carly Nicholson, 28, from Calgary. "You do have to take a lot of courses, especially in private practices."

"That's been something that UBC's fully aware that's one of the issues," said clinical education cohort coordinator Robin Roots, adding a position has been created to help recent graduates.

"It can be intimidating as a new grad going to a community where you may be the only physio," added Tory Prentice, 24, of Logan Lake.

"But (it's) also a really good learning opportunity and I feel like you would get good fast," she said with a laugh, "and you would teach yourself very quickly."

Michaela Toffoli would like to see more training in the north and says the video conferencing approach, with support in Prince George, works well.

"We still have face-to-face access to instructors and easy access to instructors in Vancouver," said the 27-year-old from Delta, adding she likes the group dynamic of 20 students.

"I actually kind of prefer it because it's a smaller group," she said.

Conrad pointed to the Northern Medical Program partnership between UBC and UNBC for physicians as the ideal model.

"It's been a huge success in retaining doctors in the north. It'd be really nice to follow in their footsteps."