Prince George is experiencing climate change at an accelerated rate than the global average. This means the local climate is changing so fast that infrastructure can’t keep up.

The city recently completed its 2020 Climate Change Adaptation Report, which contains climate projections to 2050 and the expected impacts associated with a changing climate.

“We have seen significant changes to our winters. Anyone that has lived in Prince George for over a decade can speak to how our winter temperatures have warmed,” said Andrea Byrne, Environmental Coordinator in Development Services, when presenting the report to city council on March 8.

Since 1945, the amount of annual days below -25 C decreased from 18 to seven days per year and the minimum winter temperature has increased by approximately nine degrees.

So instead of -40 C, the maximum is now -31 C.

“We are also starting to see a decrease in our summer precipitation by about approximately 28.5 per cent since 1942 which we know contributed to our wildfire seasons and increased residential sprinkling demands,” adds Bryne.

The report projects that by 2050, Prince George can expect an annual temperature increase by an additional 2 C, have six more days above 30 C, 2.5 fewer days below -30 C, and more extreme precipitation events.

“That may not sound so bad to those of us that enjoy the summer, however, we need to appreciate just how quickly this is happening on a global scale and that our natural and built environment just can’t keep up,” says Bryne.

“This is a very short window for adaptation.”

What does climate change mean locally?

These climatic changes can be linked to the mountain pine beetle infestation in the early 2000s as warmer winters were not able to keep the pest populations at bay, and the extreme wildfire events of 2017 and 2018.

The warmer winter weather has also resulted in changes to city snow and ice-control operations, increased localized flooding events and impacts to the road infrastructure.

“Operationally, the warmer winters have been a significant challenge,” says Bryne, noting that rain-on-snow events cause frozen catch basins to flood and the increased cost of ice management.

“We are also seeing those freeze-thaw cycles, so we are jumping above and below zero a lot more now and anyone that has driven out there can see just see how hard those mild winters have been on our roads. There’s a lot of potholes out there this year.”

The city has already patched more than 170 potholes in 2021 as a wet autumn, followed by the cold snap and heavy snowfall in February, provided an ideal environment for road deterioration.

“This is one of the earliest years I’ve seen us have as much damage on our roadways then we have in the past decade I’d suspect,” noted Mayor Lyn Hall. “Every year it seems to get progressively worse.”

Looking to the future, Prince George will continue to see rising annual mean temperatures, with the most significant rises occurring in the winter months.

Prince George will also continue to see changes in precipitation patterns resulting in drier summers and increased rainfall compared to snowfall in the winter, and more frequent and extreme weather events.

“We can expect more extreme rainfall events which can lead to rainfall exceeding the capacity of our drainage system and damaging our ageing infrastructure,” says Bryne.

“We can expect that to result in property damage, loss of our riverfront trails and infiltration of backups of our sanitary sewer system.”

What is climate change adaptation?

The city's report focuses on climate change adaptation, which acknowledges climate change impacts affecting the community and examines actions to reduce risks.

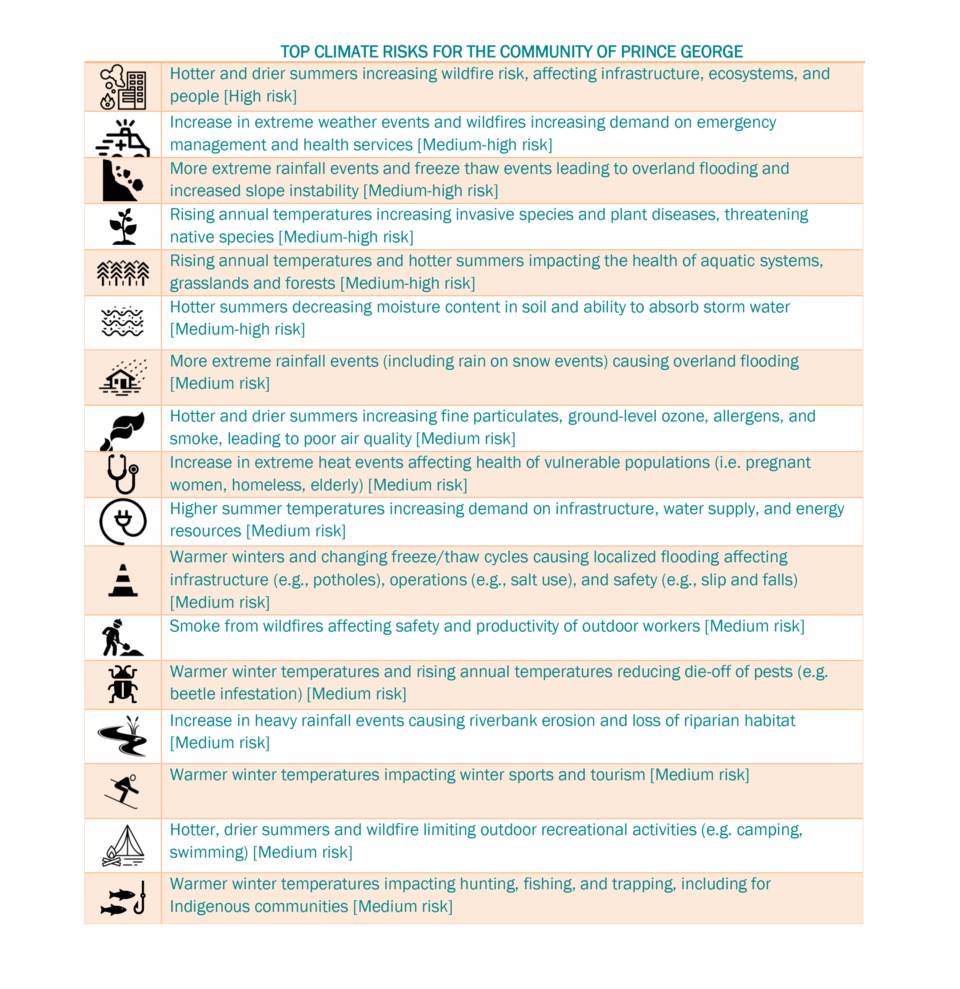

It identified 18 priority climate risks Prince George may expect in a changing climate, and actions that can be taken to reduce the city and community’s vulnerability to these risks.

However, transportation and stormwater were named as priority focus areas that require the most pertinent action for the city.

“Adaptation actions include protecting our homes from flood and wildfire, improving our emergency response procedures and upgrading infrastructure to handle changing climate like larger catch basins to handle bigger rain events,” says Bryne.

She also noted the city’s new Integrated Stormwater Management Plan as an example of preparing the community to be more resilient.

Council approved the Climate Change Mitigation Plan in May 2020, which sets short, medium and long-term targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions as mitigation refers to reducing activities that contribute to climate change, primarily fossil fuel use.

Bryne says the next step is to align the priorities in both the adaptation and mitigation reports.

“Having two different plans seems confusing, so we want to align the actions from both plans and working on developing a five-year work plan that streamlines those actions to be as efficient as possible,” says Bryne.

“Integrating those two streams, climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation, is essential for moving our community forward on climate change.”

The Canadian Centre for Climate Services (CCCS) of Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) has also asked if adaptation report can be added to their case study library to assist other Canadian municipalities and residents.

Top Climate Change Risks in Prince George via the 2020 Climate Change Adaptation Report. By City of Prince George

Top Climate Change Risks in Prince George via the 2020 Climate Change Adaptation Report. By City of Prince George