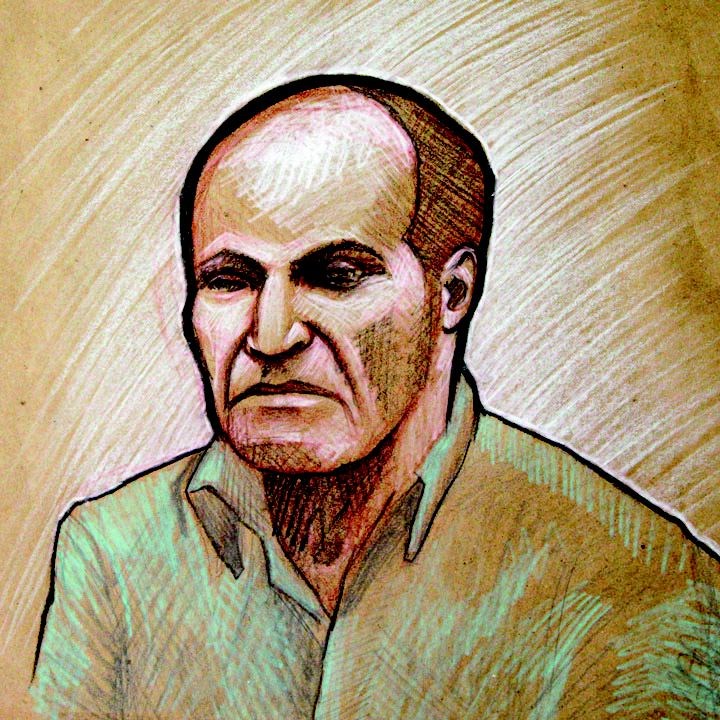

The B.C. Court of Appeal has upheld the second-degree murder conviction against Denis Florian Ratte in the 1997 shooting death of his wife, Wendy Ann Twiss Ratt.

In a decision issued Friday, the court dismissed Ratt's appeal of a November 2010 conviction following a Supreme Court jury trial at the Prince George courthouse that has him serving a life sentence without eligibility for parole for 15 years.

On Aug. 18, 1997, Wendy Ann Twiss Ratt, 44 at the time, was reported missing and the family's van was found parked at a supermarket, now Value Village.

The case languished for years but in 2008, her husband became the subject of an elaborate undercover operation, known as a "Mr. Big" sting, in which police officers posed as high-level gangsters to gain the suspect's trust.

During the trial, the jury watched a video recorded with a concealed camera, where Ratt took the officers to the scene of the shooting nin the backyard of the family's home, and then to a wooded area east of the city where he told them he dumped her body, which has never been found.

Crown counsel Marie Louise Ahrens argued Ratt committed the murder because he incurred a large gambling debt while unable to work due to an injury, putting the family in financial stress. His wife was vocal in her disapproval with his actions and Ratt, who felt he was in the "doghouse," could not take it anymore and committed the murder, the jury was told.

Ratt's appeal was based on the assertion that the trial judge, Justice Glenn Parrett, erred in three ways: by allowing character evidence from his daughter, Anna Sieppert, when his character had not been put in issue; allowing a police officer to state her opinion that Wendy Ratte never left Prince George on the day she disappeared; and allowing "prejudicial hearsay evidence" from three witnesses.

But in the ruling, written by Justice David Harris in concurrence with Justices Ian Donald and Nicole Garson, all three grounds were dismissed. He noted none of the evidence raised in the appeal was objected to during the trial and, in some instances, was elicited by the defence in cross-examination.

"Moreover, defence council did not ask the trial judge to provide any limiting instruction [to the jury] with respect to any of the evidence challenged on appeal, even though there were extensive discussions about what the charges should contain," Harris wrote.

Sieppert described her mother as "open and honest" and her father as "secretive" and someone who "kept things to himself" which Ratt's defence counsel argued during the appeal would lead the jury to believe he could kill his wife and keep it secret for 10 years.

But Harris disagreed.

"I do not think that someone who is secretive and keeps things to themselves, but is calm and patient, would be taken by any jury to be of a character or disposition to kill their spouse," Harris wrote.

Harris did have problems with the officer providing an opinion, saying it went beyond stating the facts, but noted defence did not raise an objection during the trial and when set in the context of the whole trial, was not enough to prejudice the proceedings.

Harris also upheld the use of hearsay evidence regarding Ratt's gambling debt, noting also that the testimony was presented at trial without objection,

Alleged to have been $10,000 put on a family credit card, Ratt testified it was $2,000 to $3,000 although he acknowledged his wife believed it was $10,000 despite trying to explain to her it was not that high.

Harris found the evidence did as much to explain defence counsel's theory that she left her family as Crown's that it gave Ratt motive to commit the act.

Harris also noted defence counsel used hearsay evidence regarding whether Wendy Ratt had run away from her family as a teenager, implying that if she did it once she might have done it again, and drew out additional hearsay evidence alleging her interest in a same-sex relationship.