A small Canadian flag stands in front of the birch tree in the Fitzpatrick's front lawn year-round. The family's three boys played under those same leaves as children. They replace it as the colours fade, but the week before Remembrance Day, the leaf is bright red.

Another maple marks Cpl. Darren Fitzpatrick's grave.

Now that symbol has a power that makes his mother's voice waver and his father quiet.

"We look at the flag way different now," says Colleen.

After Darren died of injuries in March 2010 at age 21, seeing it fly and singing the national anthem at events was particularly tough.

"For the first couple years we couldn't make it through," says Jim, as the flag took on the memories of what their son fought for, the Skype calls from Afghanistan where he told them what he witnessed made it real for him. "He knew why he was there."

Darren was the first soldier raised in Prince George to die in combat since the Second World War.

"When you've lost someone fighting for your freedoms the flag represents so much more," says Colleen through tears.

This year, she's been named the National Silver Cross Mother by the Royal Canadian Legion, tasked to lay the wreath before the the National War Memorial in Ottawa tomorrow, representing all mothers who have lost children. She doesn't see herself as a symbol.

"I share an experience with many families and many other mothers and fathers ... I understand their grief to some degree," says Colleen from her living room.

She and Jim left for Ottawa on Monday ahead of today's ceremony.

"We share a common bond, but it's not a group you ever want to be a part of."

She had a busy week planned in the nation's capital, with three days straight of responsibilities tied to that title. It's an honour, she says. It's humbling. It enables her to share a message about military - about service - but they don't want the spotlight.

"We talk about this a lot. Anything that we do is honouring our son," says Jim as Colleen finishes his sentence: "And the others that have served.

"They've sacrificed, they've come home, but they're definitely changed," she says.

"There are people that have gone over and didn't come back but it's also important not to forget those that fought beside them. We keep in touch with a lot of the guys who were in his troop and they've given of themselves. Some of them struggle with PTSD," says Jim. Support for that trauma is important, they say.

"That's going to affect them for the rest of their lives. Their sacrifices will be with them as well," adds Colleen.

Inside the couple's Prince George home where they raised Darren from age three, a folded flag with two medals and two poppies pinned to his beret sit in a wooden box, a constant coffee table centrepiece.

Behind, the couch is draped in a patriotic quilt, handmade by one of the many Canadians who sent similar gifts.

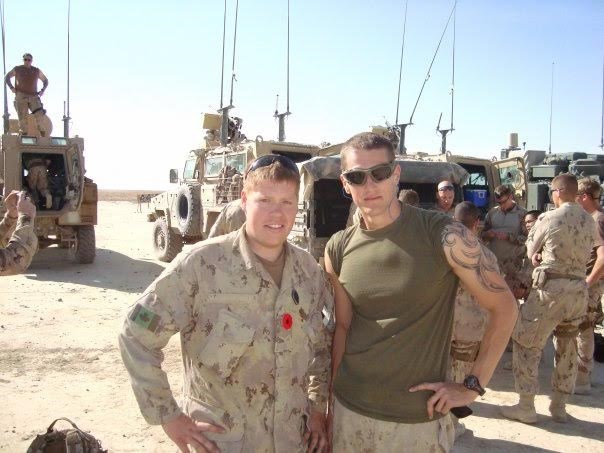

Above the mantelpiece, a framed formal military picture, one of the few where Darren isn't smiling. Just a little over, on the wall, Colleen's favourite: the last taken of Michael, Darren and Sean, brotherly grins an obvious genealogy.

Every day is Remembrance Day for their family, Colleen says, but October and November is the toughest time of year.

"We look for ways to keep Darren's memory and his spirit alive. We look for ways to make a positive impact because that was Darren was all about. He was about making a difference and that's what we want to do," she says.

This year, with the national recognition that comes with her position, Colleen has been telling his story many more times.

Strewn across the kitchen table are tokens that help them remember. Military coins, including one found in Darren's pocket when he was injured. An album memorializing his three funeral services in Kandahar, where he was injured, Edmonton, where he died, and Prince George, where he remains. A book of poetry and a stack of comments from strangers that thank them for their sacrifice. The poster cousins made of happy times with "little D" as he was known to family before he became "Fitzy" to friends.

Born five pounds, 14 ounces, he was a little red head with "a big beautiful smile," a loyal friend and a caring person.

Every day is a new journey and it doesn't get any less painful she explains through glassy eyes.

"It just gets a little more bearable every day. You learn how to live with a bit of an emptiness," she says, her voice catching on that last word. "You learn to live different."

"We call these bumps," says Jim, who makes tea and is ready with calm words of support.

"Speed bumps," she laughs through the tears. "When we have an emotional moment we call it speed bumps.... I've cried in front of a lot of people and it doesn't matter anymore. You want to be stoic and you want to be courageous because you want to represent your loved ones, right? But... there's always a soft spot.

"We've been asked many times if our loved ones going overseas, was it worth it? Was it in vain? And I always say, if you value your freedom it's not in vain."

The last week as the news spread she would represent families of the fallen, many reporters reached out to their family. While painful, she doesn't resist the questions that make her voice catch with Darren's memory.

She thinks of advice they got early on: "You have to tell the story 10,000 times ... for the healing so it's difficult, but it's something you want to do," she says. "We've been telling the story almost every day for seven years and it's a story we want to tell."

Reliving the tragedy can be difficult, but she agrees it's necessary to fight through the bittersweet moments.

"You take away the sweet things and it's just bitter. These positive things are what we look for to help us through our journey."

Prince George has helped make that happen, through blood drives in honour of the blood transfusions Darren received in his final two weeks, the creation of the Cpl. Darren Fitzpatrick Bravery Park, which opened in September and donations to two student bursaries in his honour.

"We want their memories to be alive and people to remember who they were, as individuals, and what they contributed to our freedoms."

She calls Darren a mischievous little redhead who lived life to the fullest.

"A little bit of that redhead spirit was always with him."

She references that shock of hair when talking of his resilience in the hospital after his grievous injury by an improvised explosive device during a foot patrol. First he was treated at the Canadian base in Kandahar and then a German medical centre before being flown to the Edmonton hospital two weeks later.

The flight was hard on him.

"It was a shock for a lot of people that he passed the next day," she says, but the infection had gone systemic. "It was like he knew he was home. Next day he passed."

"That was his only request, actually," adds Jim.

At the time, even though he was so seriously injured, the family held hope he would live. Still the two are grateful for those last few days together.

"You live hour by hour...It's traumatic when you're living it, but now I can't imagine not having those two weeks," says Colleen, which is more than some of the families she'll represent in Ottawa got with their children.

"They didn't get the opportunity to say goodbye. For me they're truly inspirational."