It's 1995. A few months have passed since the March headlines with the revelation that the naked, screaming girl in the photo that defined the Vietnam War lives in Canada.

A phone rings and Denise Chong picks up.

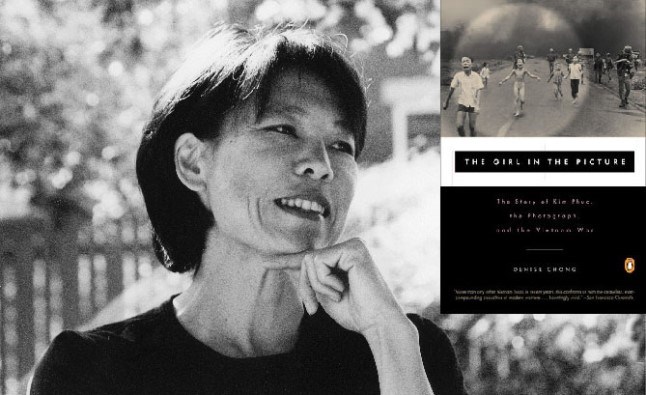

On the other end of the line, her book publisher tells her they have acquired the book rights to Kim Phuc's story.

Would she write it?

"I said 'Well, I've got to meet her.' My first thought was she was a child. War is an assault on the memory. I wanted to know what there was of integrity there. That picture just freezes in your mind. You don't really think what is she running to or what is she running from."

Chong recalled that conversation Wednesday in a phone interview from the same Ottawa kitchen where she took that call more than 20 year ago.

"I'm getting goosebumps just saying it," says Chong, a day before she jumped on a plane to her hometown of Prince George, where she will be visiting with family and friends, and also speaking about the book she spent five years of her life researching and writing.

Phuc will also be in Prince George on Saturday as the guest speaker at the Bob Ewert Memorial Dinner and Lecture, an annual fundraising event for the Northern Medical Programs Trust.

On June 8, 1972, Associated Press photographer Nick Ut captured a picture of villagers and South Vietnamese troops fleeing Trang Bang, north of Saigon, as planes dropped bombs overhead, with the nine-year-old Phuc, centred in his frame.

And though Chong ultimately titled the book The Girl in the Picture, it took more than that harrowing shot to compel her to commit to Phuc's story.

"If only because you know you're going to immerse yourself and it's going to be years before you come out again. You know that something has to drive you forward."

At the time Chong had young children and she remembers speaking to her husband Roger Smith, a CTV journalist, reporting on yet another war from Belgrade.

"We could hear the sirens going," Chong says. "So you know that war repeats, repeats and you want to go back and you want to explore that whole trauma and moral ambiguity of war."

The pull of that tale - caught in an image - is just a fragment of a larger story.

"Once I got to Vietnam and did the research I knew that Kim was but part of the story, that I was going to talk about Vietnam the country as opposed to Vietnam the war."

Very little had been written about post-war Vietnam, says Chong, who published the book in 1999, earning a nomination for the Governor General's Literary Award.

"It had just fallen off the radar of the West."

It's those details, that nuance that Chong seems to pride.

"I suppose there's a life and there's a social context to that life. Had I not gone into Vietnam then it would be incomplete in so many ways, her story. I wouldn't have portrayed what life was like in a war-torn country. Vietnam was a country, it wasn't just a war."

Chong hasn't been back, but she's seen pieces of the country's past in other travels.

Just last year she spent time in Laos and Cambodia, both of which border Vietnam.

"I visited bars decorated with remnants of U.S. bombs people are still digging up. So you're just walking through that history of it."

The Phuc photo has since taken on new meaning for Chong who draws connections to the image of toddler Alan Kurdi, his lifeless body washed up on a Turkish beach.

"It evokes the same kind of reaction in the innocence and the flight from violence and war and the same sort of sequence of events get sets into motion," she says.

"You're fleeing, you're looking for safe haven, you're a refugee. You've got to resettle... I thought about it a lot then."

It took years and hundreds of hours of interviews for Chong to peel back the layers of Phuc's life - the months in hospital, Phuc's years as a propaganda tool under the thumb of the communist Vietnamese government and fleeing to Canada in 1992.

"It's not as if someone sits down and then says I'm going to tell you A to Z my life story. It's all unordered, fragments, it hasn't been articulated. It's digging into memory that you've kind of repressed."

It took patience and doggedness to build that trust to help Phuc overcome "her unfamiliarity with speaking her mind."

"She'd had minders, so she'd been used to speaking the same line for a long time and being guarded," Chong says.

"That took a long time and it certainly did come. There were lots of tears and quivering lips and astonishment on her part because you're a child. And there's an old adage - the closer you are to war, the less you know what is going on."

Chong remembers the moment when she knew she had truly broken through those barriers.

"(Phuc) came downstairs in something sleeveless - and she'd always covered her arms in my presence before - so I could just see that scar tissue wrapping her arms, where her burn was," Chong recalls.

Aside from Phuc's scars, and the famous photo of the moments after they burned her skin, Chong always comes back to Phuc's smile.

"She's got the most brilliant smile and ironically her family named her 'Phuc' It means happiness," says Chong, a clear contrast to the ravages of war.

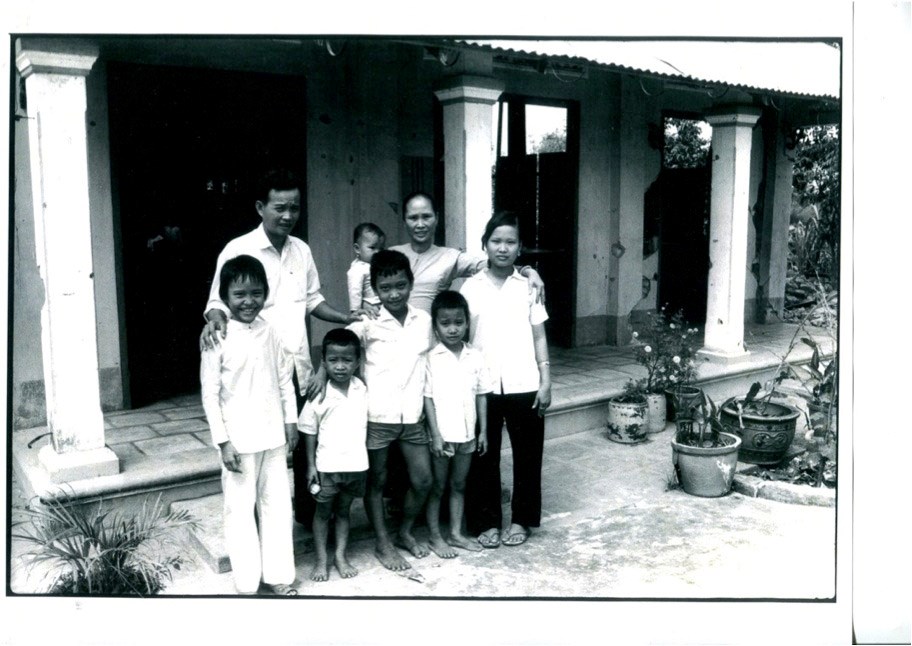

"I can still see where the mortars hit in their backyard of their house. I could still see grapefruit trees severed at the base. I could still see the mortar marks in the temple where Kim Phuc had been hiding with mostly women and children.

"You contrast that with the smiles of the people. It's that contrast, (that) just brings home to you what has to survive the horribleness of war."

Chong also speaks of Phuc's forgiveness and says audience members at the Ewert dinner Saturday will be both shocked and have their faith in humanity restored.

"I've seen her effect on people and there's something, I think you see inside yourself. You see in your mind's eye as she speaks, this child, running with all that swirling black smoke," Chong says.

"You can't get that picture out of your mind and then you see her up there. You have a whole mix of emotions. You have the sort of collective guilt that we engage in war," says Chong, and yet Phuc brings another message, having "been in the eye of history" and emerged from it:

"With forgiveness there's a future."

Tickets are still available to the Ewert Dinner until noon today. For more information, call 250-960-5750.

Chong will be speaking today about writing The Girl in the Picture at UNBC's Canfor Theatre. She'll also present a free memoir writing workshop on Thursday at Books and Company.