Editor's note: This story was first published in the Citizen print edition in Nov. 10, 2001.

I never knew my Uncle Ted.

Like so many thousands of Canadians who enlisted in the Second World War, the man I was named after was killed in action, long before I was born.

Samuel Edward (Ted) Clarke was the third oldest in a family of eight kids growing up on a farm in Parkside, Sask., a rural community of about 150 people located 50 kilometres west of Prince Albert.

Not long after the war broke out in 1939, the oldest boy in the family, my dad Jim, joined the Royal Canadian Air Force and Ted couldn't wait to follow in his brother's footsteps. He became an army cadet at age 17 and on Oct. 6, 1941, the day after his 18th birthday, he signed up for the air force.

After about of year of training as a pilot in Claresholm, Alta., Saskatoon and Prince Albert, Ted finally got his wings, graduating with the highest marks in his class. Unlike my dad, who badly wanted to fly overseas but was more urgently needed in Canada to train more pilots, Ted was sent to Europe in January 1942, where he would join his best buddies from Parkside — Leon Roberts and David Olsvik. All three had enlisted in the air force within months of each other as soon as they were old enough. Leon was a few months older than the other two and was sent to England first.

Ted was popular with his fellow airmen in Moose Squadron 419 and in June 1943 he was promoted to flight sergeant. He loved flying but realized with every bombing mission the risk of being shot down was always there. In one of his letters home, he wrote:

"Yesterday we had a horrible trip which lasted seven hours but the good old Wellington brought us home. Can you imagine flying 17 1/2 tons every day?

"I'm eagerly looking forward to the day when this is all over and people can live a normal happy life for another few years."

Ted grew up in the depression years of the ‘30s when his family had very little money but, as cattle and grain farmers, always had plenty to eat. People arrived in Parkside on the train looking for work and Ted, with his gregarious and generous nature, had a knack for bringing home strangers whom his mother fed and boarded for the night. When they left, they'd always go carrying a loaf of fresh-baked bread.

As a Boy Scout, Ted went out of his way to perform at least one good deed a day and he left his younger siblings in awe over his patriotism when he'd snap to attention whenever 'O Canada' or 'God Save the King' was broadcast over the battery-powered radio. He inherited his mother’s love for music and could sing any song.

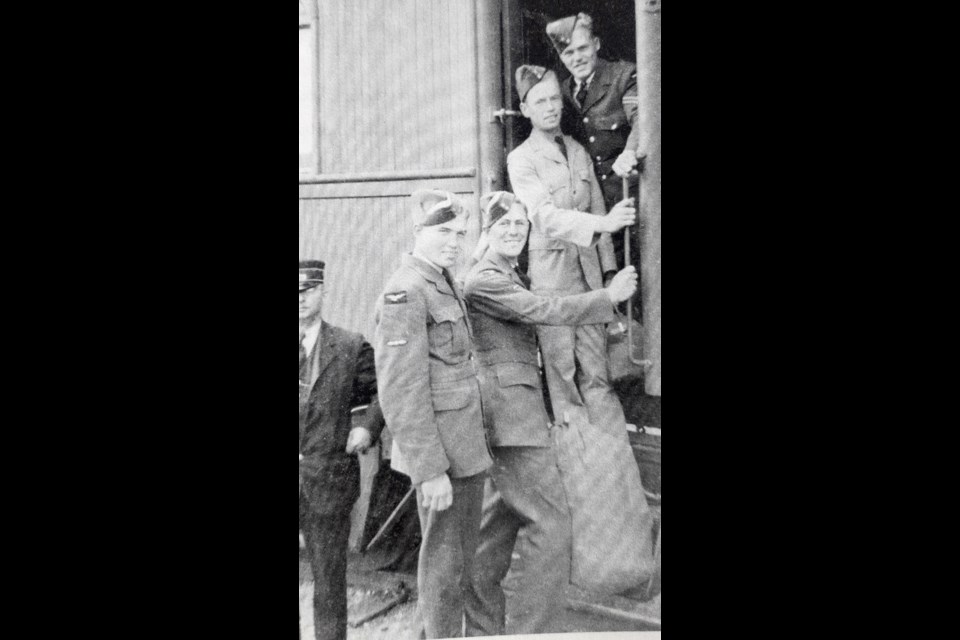

While overseas, he always sent home half his wages and specified some of the money be used for a family holiday at Emerald Lake, the place where he'd met his girlfriend Rita Wodlinger. He always kept a photo of Rita in his left shirt pocket. Ted came home for the end of the Christmas holidays in 1942 and stayed until January, when he was sent off to England. The entire school in Parkside was there to see him off at the train station. It was the last time they would ever see him.

In his last letter home, Ted tells of the joy he received when he found 11 letters waiting for him at the base. But his happiness soon gave way to tears:

"Isn't it funny how in the quiet of evening, especially, one becomes very sentimental. I will tell you this Mum because I know you will understand. I have just been crying like a baby for the first time since I left Canada. I don't exactly know why, I think it was just to relieve myself. Don't you think a good cry once in a while does a person a world of good? I assure you when I come home there will be more crying — but of joy.

"We haven't had much work lately due to rough weather. I become so depressed on the ground. It is a wonderful feeling to look out and see those four motors turning, the crew happy and confident and that every time we fly brings us that much closer to our folks.

"For Christmas the only thing I ask is I won't have to spend my fourth one away from home. Besides that, I ask God that you will all be waiting for me when I come home."

In one of his letters to my dad, Ted said he felt he was wasting the best years of his life and told Dad he should do whatever it takes to avoid seeing for himself the horrors of the war overseas.

The fall/winter of 1943-44 was a tragic one for Parkside. Bob Roberts had just returned from a wedding in Prince Albert when a station agent arrived at his door and handed him a telegram which said his son Leon's plane had been shot down over Nettersheim, Germany on Oct. 22.

A few weeks later, on Nov. 26, a telegram arrived at the Clarke farm two miles west of Parkside. Ted and his crew were missing in action and presumed dead following a bombing raid over Stuttgart, Germany. The telegram gave the date the plane went down. It was the night my grandmother heard Ted calling to her in her sleep.

The Olsvik family received their telegram which told of David's death on Feb. 20, 1944, when he had only one or two missions left to fulfill his commitment to the war effort.

Three telegrams. Three lost 20-year-old sons. All killed within a few months of each other, and the small community of Parkside was left with just their memories.

My grandmother always hated Bing Crosby's White Christmas because it reminded her of one of the last letters she received from Ted. The song had just come out and he told her they were playing it a lot on the radio.

In a letter my Aunt Betty (Toop) wrote to the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix she told of her mother's grief in the years that followed the war:

"My mother kept hoping he would be found. She couldn't accept the fact he was dead. More letters from Ottawa confirmed the fact he wouldn't be back. My mother was never the same after. She never let go of her grief.

"When she died, we found (Ted's) letters and those from the War Department tied with a blue ribbon. The paper on those letters was soft from years of unfolding and refolding. How many times she read them over we will never know. They were all she had left of her beloved son."

Lest we forget.