A supercomputer at the University of Northern British Columbia has helped an international team of researchers discover that the rate of mass loss from Earth’s glaciers is accelerating.

The computer, jointly funded by UNBC and the Hakai Institute, constructed digital elevation models based on more than 440,000 satellite images.

“Processing spaceborne digital imagery to measure changes in surface elevation requires enormous computation power,” said UNBC professor and Hakai affiliate Dr. Brian Menounos, the Canada Research Chair in Glacier Change. “We needed an equivalent of about 584 modern computers running for about a year to derive these elevation models. Looked at another way, the generation of the elevation models required over five million compute hours.”

The computations are part of a paper published in the April 29 issue of Nature that found that between 2000 and 2004, glaciers lost 227 gigatonnes of ice per year, but between 2015 and 2019, this rate increased to 298 gigatonnes per year. A gigatonne is equivalent to one billion tonnes. Loss of water from glaciers represents about 21 percent of the observed rise in sea levels over the last 20 years – some 0.74 millimetres a year.

Researchers, led by ETH Zurich and University of Toulouse doctoral student Romain Hugonnet, measured elevation change from all of Earth’s glaciers – some 220,000 in total. Hugonnet is also a former research associate at UNBC.

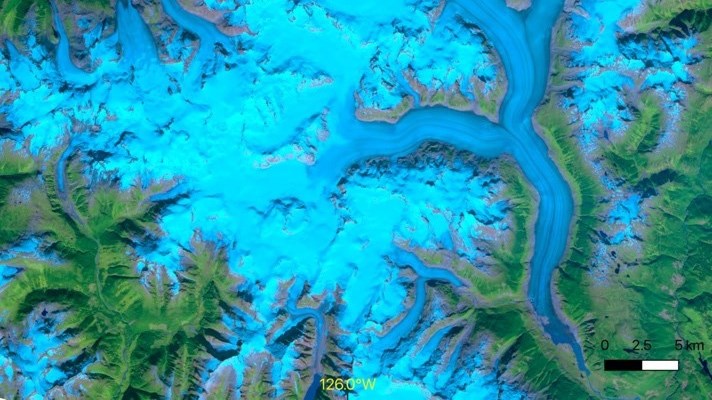

The researchers used the processed satellite images acquired from NASA’s ASTER sensor to measure elevation change over glacierized terrain through time.

“The UNBC and Hakai Institute computer facilities allowed us to generate time series of surface elevation, essentially time-varying topographies, at 100-metre resolution for about one-half of a billion individual locations over Earth’s glaciers and their surroundings,” Hugonnet said.

The researchers found that over the last 20 years, glacier mass loss from North American glaciers represented about one-half of the global total with one-quarter coming from glaciers in Alaska and those that straddle the Alaska-Canada border.

Glaciers and icecaps in the eastern Canadian Arctic contributed an additional 21 percent with three percent originating from glaciers in central and southern British Columbia, Alberta and the conterminous United States.

The researchers also found that some of the world’s highest rates of mass loss over the last decade occurred in southern Alaska and western Canada.

“In addition to providing a detailed response of glaciers to regional and climate variability, the dataset will provide important observational data required to validate and improve physically-based models used to forecast changes in glacier and runoff in the decades ahead,” Menounos says.

Other key institutions that co-lead this work included Ulster University in the UK, the University of Oslo in Norway.