Victoria Youmans says she hasn't seen Arrow Lakes Reservoir looking so low in more than 20 years.

The resident of Nakusp on the shores of the reservoir in British Columbia's southern Interior says she's seen thousands of dead fish on the shore, and the receding waterline means boat access has been cut to waterfront properties. Instead of lapping waters, some homes now face an expanse of sucking quicksand.

Drought is part of reason. But so too is the Columbia River Treaty with the United States that obligates B.C. to direct water from the reservoir across the border at American behest.

The grim scenes described by Youmans illustrate the stakes in ongoing talks between Canadian and U.S. negotiators to modernize the 62-year-old treaty, as the increased risk of extreme weather weighs on both sides. Part of the treaty that gives the United States direct control over a portion of the water in Arrow Lakes Reservoir and two other B.C. dams is set to expire in September 2024.

"I would say that when it was negotiated in 1961 and entered into force in 1964, it probably was one of the most important — if not the most important — water treaties in the world," said Nigel Bankes, professor emeritus at the University of Calgary's Faculty of Law, whose expertise includes the Columbia River Treaty.

"Its significance was really that it provided for the co-operative development of the Columbia River — the co-operative development of storage for flood control and power purposes, and for a sharing of the benefits associated with those developments."

The treaty was forged after catastrophic flooding of the Columbia River in 1948 destroyed the city of Vanport, Ore., near Portland.

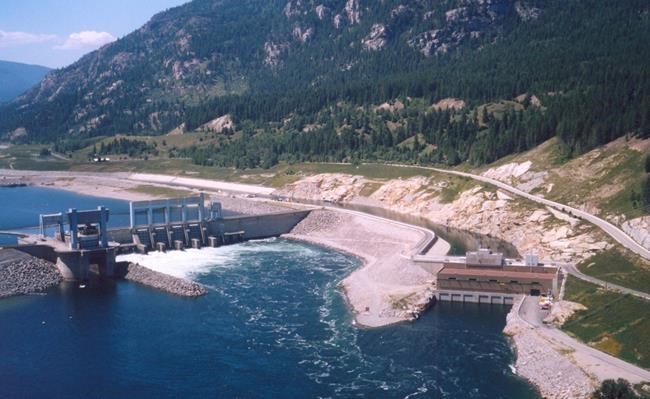

It led to the creation of three dams in B.C. and a fourth in Montana in the Columbia's drainage basin, serving both flood control and hydropower generation.

But recent extreme weather — such as this year's severe drought in B.C. — has exposed problems in the agreement that residents of the Columbia River Basin say need to be urgently addressed.

The 230-kilometre-long Arrow Lakes Reservoir — made up of Upper Arrow Lake and Lower Arrow Lake — was created when the Hugh Keenleyside Dam was built in 1968 under the treaty.

The reservoir's water level had fallen to 423.7 metres above sea level on Tuesday — a low not reached in more than two decades.

Nakusp resident Youmans said what's even more concerning is that it's only October, and the lakes usually don't reach their lowest annual levels until late winter or early spring.

"I personally have never seen it this low, and I've lived here for over 20 years," said Youmans, who is among 3,900 members of a Facebook group that wants to "slow the flow of Arrow Lakes" to the United States.

She says the low water levels are hampering tourism and recreation on the lake, located about 600 km east of Vancouver.

There are other commercial concerns. Nakusp Mayor Tom Zeleznik said low water levels had rendered parts of the reservoir unnavigable for vessels carrying logs, resulting in the closure of some businesses, and forcing reliance on costlier land transport.

Katrine Conroy, the provincial minister on the Columbia River Treaty file and the MLA representing Kootenay West, said the province is legally obligated by the treaty to direct water to the United States "for flood protection, power-generation purposes, as well as for fish."

"It's really frustrating to be faced with a situation that feels like there's very little that you can do to fix it," Conroy said in an information session held for West Kootenay residents on Oct. 18, saying her position as the minister responsible for the treaty does not give her a seat at the negotiating table.

The latest round of negotiations, which were the 19th since talks began in 2018, concluded in Portland on Oct. 13.

"(My) position doesn't give me a magic wand," Conroy said. "I can't cancel a treaty or change its terms or requirements … Often as a government minister, I'm confronted by problems and issues that are hundreds of kilometres away, but for me, this one hits very, very close to home. It's in my backyard."

Conroy is also B.C.'s minister of finance.

Federal, provincial and First Nations delegates are represented at the talks with U.S. authorities.

If a new flood-control agreement isn't reached by September next year, the treaty currently calls for a shift to an "ad hoc" regime, with U.S. authorities having to rely on their own dams' capacity for flood control before being able to call upon Canadian dams to hold back water as necessary.

The concern, Bankes said, is that nobody knows exactly what an ad hoc regime will look like because it has never been done before.

"Currently, as I understand it, the dam operators start thinking about flood control operations in February," Bankes said. "So, you need long lead-ups to be able to achieve target flows down in Washington and Oregon. "That, I think, is the biggest issue, and obviously it should be a huge driver for the United States. What amazes me is that they haven't got it figured out now, because 11 months is not a long time."

The U.S. army Corps of Engineers, which built and operates the American treaty dam in Montana as well as a number of dams downriver in the Columbia River Basin such as the Bonneville Dam, warned Oregon and Washington residents in a September information session that waterflow may become "unpredictable" if Canada moves to an ad hoc regime.

Development has proliferated on historical Columbia River flood plains in the United States since the treaty came into effect, and the Corps of Engineers said an ad hoc regime could lead to flooding and disruptions to transport corridors including the I-5 bridge linking Oregon and Washington.

"At this point, we just simply don't know the actual changes in reservoir operations or potential changes in flooding, because we don't know how Canada will be operating their system," Geoff Van Epps, Commander of the U.S. army Corps of Engineers' Northwest Division, told the information session.

Speaking to West Kootenay residents with Conroy, Canadian treaty negotiator Stephen Gluck said while an ad hoc regime will give Canada more control over waterflow "in theory," it also introduces uncertainty.

"I will say that even though we continue to negotiate, there is an emerging acceptance that a modernized (treaty) must include Canadian flexibility," Gluck said.

Kathy Eichenberger, B.C.'s lead negotiator, told residents the province received roughly $420 million last year in the "Canadian entitlement" from power generation at U.S. dams based on waterflows from Canada.

Typically, the province receives about $150 million to $200 million a year, funding that goes into consolidated revenue.

Eichenberger said the dams also helped avert flooding in the B.C. communities of Trail and Castlegar in 2012.

"The key is, Canada and B.C., we entered into this treaty willingly, as partners with the United States," Eichenberger said. "So, we are committed, as the U.S. is committed, to upholding to treaty requirements."

For residents such as Youmans, however, it is "beyond frustrating" to see Washington's Franklin D Roosevelt Lake — downriver from the Canadian dams — operating at normal water levels, while Arrow Lakes Reservoir recedes.

"Unfortunately, there's nothing we can do with what's happened now," Youmans said. "All we can do is move forward and be heard on the upcoming and ongoing negotiations."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 25, 2023.

Chuck Chiang, The Canadian Press

Note to readers: This is a corrected story. Previous versions said the Columbia Basin Trust was funded by the Canadian cash entitlement from the treaty, and that the entitlement was directed at regions affected by Columbia River dams.