Part two of a three-part series. For Part 1, click here. For Part 3, click here.

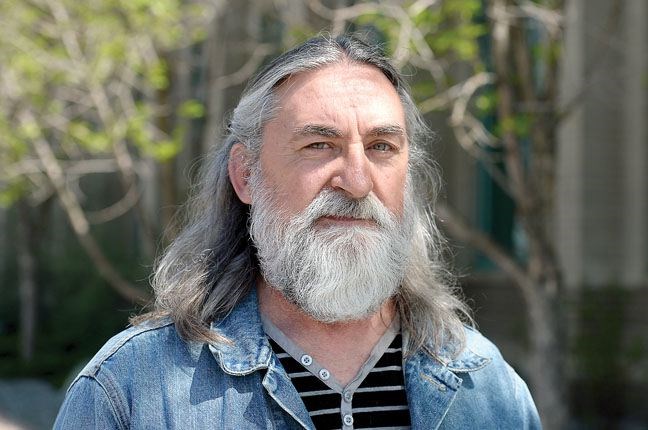

The words Don Zwozdesky uses to describe life now are lost to him like the last three years since Lakeland Mills exploded around him.

"Turmoil," he finally whispers, "Just less or more turmoil all the time."

Zwozdesky was one of 22 who survived the April 2012 sawmill blast that killed Glenn Roche and Alan Little.

"I exist. I don't live," he says.

He's been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder stemming from that April 2012 day when Zwozdesky watched a burnt Roche emerge from the flaming building.

"I knew who he was because of his voice, his sound. His eyeballs weren't burnt. The rest of him was burnt."

Zwozdesky is haunted by the questions Roche asked him: "I'm still on fire" and "is my face gone?" and "I'm going to die, right?"

"That kind of messed up my world," says Zwozdesky, who still dreams of the disaster.

"It's very painful."

He tries not to take medication because he knows it can't erase those images.

He catches images of men who, for a moment, he thinks are Little and Roche.

Talking can make it worse, and he finds people judge him, so for the most part he isolates himself, preferring his home in Nukko Lake.

"You've got two choices: explain or avoid the situation," says Zwozdesky, holding up two fingers. "You know what the easiest one is? Avoid. So stay home."

Processing information can prove difficult, but the reaction people give can be worse.

"The next thing they will do: They. Will. Talk. Slower," says Zwozdesky, deliberately pauseing between the words.

It makes him feel stupid.

"I already feel alienated right from the event. It's weird how you feel odd and different, all the people around you help you feel that way," he says.

"The words you choose to use to explain how you're feeling very rarely works for anybody," says Zwozdesky, adding he only feels comfortable with the others in the blast.

"There's things we don't have to explain."

He's often anxious and his mind gets stuck on what might seem like small things, like knowing an answer to a question, remembering why he entered the kitchen or if he locked the car door.

"It's not just a little worry," he says.

"It's huge. It's almost like mini-crises all the time now."

He rattles off numbers to give an idea of his ever-changing levels of stress: 240, 88, 407.

"It's never been at zero since (the explosion), never."

Sometimes, he'll just take off and drive, but he loses all concept of time. One time Zwozdesky drove 300 kilometres without realizing it. He thinks he has a brain injury beyond the PTSD, but says it hasn't been recognized.

"They tell you that the pressure wave that took off all the damn walls where I was standing was not significant enough to hurt my head or anything," Zwozdesky says.

"Just the walls."

He has a sharp pain on the side of his head and persistent aches and pains. But he's hesitant to go to doctors, fearful of the scrutiny and the doubt - that he'll be told he's making it up.

"I still don't know how to fight for myself."

Zwozdesky was an electrician at the sawmill for more than 30 years, but he hasn't worked since.

That wears on him, too; he used to see himself as the breadwinner of the family.

"I believe that's my responsibility," says the 56-year-old.

"I don't feel very good as a person."

He knows how he is now is tough on the family, says communicating is much harder and the fights more common.

"From what I was hearing I'm not too nice of a person to be around and I knew that," he said.

"I believe I'm a totally different person so, if I actually am, it would be really hard for them."

He angers quickly "at stupid things," easily frustrated by small tasks that now trip him up.

He's improved a little and has started doing the dishes without the familiar flare-ups.

"I no longer get as frustrated as I did before not being able to know where this one goes, which cupboard. I couldn't deal with that. I'd get mad and want to just smash the thing."

He tried to help a friend wire a four-way circuit.

It was a simple task for a veteran electrician, but it took more than three hours.

"I'd be embarrassed to tell people it took me 15 minutes," Zwozdesky says of his former self.

It bothers him to even touch his tools.

"I still should try to do it because I don't always want it to be that way, I really don't. It's not good being messed up."

For him, the inquest hasn't helped find answers or move forward.

"I don't count in this," says Zwozdesky, who was called as a witness and has attended every day of the inquest.

"We need to go deeper, somebody needs to be charged with this," he says.

"Going to this coroner's inquest is a sad thing to be involved in because there is no help but lots of torture because it doesn't deal with anybody admitting how they screwed up and where they screwed up. No one will admit it."