Seventeen years ago today, Anna Sorkomova was charged with committing a theft under $5,000.

Once it was determined the 23-year-old UNBC foreign exchange student from Russia was not a Canadian citizen, she was taken to the local Immigration Canada office, where her passport was seized. She was supposed to appear in court on Dec. 14, 1999, to face the charges.

She never made it.

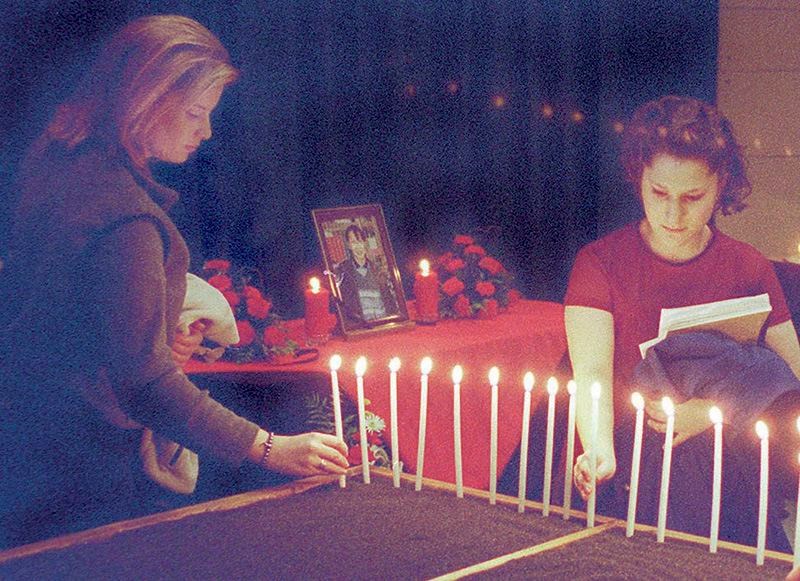

She was last seen at the UNBC residences on Dec. 12. Six weeks later, her body was found hanging in the woods not far from the university's main parking lot.

Charles Jago can't single out one favourite recollection from the plenty of good moments he had during his tenure as UNBC's president but his worst memory - Sorkomova's death - leaps immediately to his mind, historian Jonathan Swainger writes in Aspiration, the recently published account of the first 25 years of the university.

UNBC was soundly criticized for its mishandling of the Sorkomova affair.

She wasn't reported missing until six days after she was last seen when her mother in Siberia began making calls asking why her daughter hadn't come home for Christmas. The coroner's report into Sorkomova's death, released the following year, pointed to the lack of campus support for exchange students, as well as the fact the university employed a single part-time student counsellor at the time. To its credit, UNBC acted to address both issues, hiring another counsellor before the coroner's final report in February 2001.

In his book, Swainger describes the reporting of the Sorkomova affair as "sharp, often critical, and sometimes irresponsible." That comment is followed by a citation, which refers to an essay written by Deborah Poff, then UNBC's vice-president and Jago's right-hand administrator, called The Duty To Protect: Privacy And The Public University, which was published in the Journal of Academic Ethics in 2003.

Recalling Sorkomova, Poff writes: "Some of the publicity was highly irresponsible. One of the papers speculated that there was a serial killer in the area. This prompted phone calls from concerned parents in different locations. No apology ever appeared for this unwarranted speculation."

In hindsight, it is Poff's assertion, now repeated verbatim in 2016 by Swainger, that is irresponsible. The Citizen's Jan. 21, 2000 story, published before Sorkomova's body was found, linked her disappearance to a number of young women who had gone missing along the Highway 16 corridor in recent years.

The Highway of Tears designation and the devoted attention paid to the indigenous missing and murdered women along the highway and surrounding areas was still years away. Despite Poff's feelings, however, history shows it was quite reasonable for journalists at that time to ask those questions, particularly because Sorkomova was herself an indigenous woman.

Poff's article provides a context for UNBC's recent decision to not release its task force report looking into sexual violence until The Citizen obtained it through a Freedom of Information request. UNBC president Daniel Weeks announced 13 recommendations in September to tackle the issue but wouldn't release the report at the time, because of the "very sensitive topic."

In her article, Poff writes of the "historical trust and idealized notion of vocation and public good that drives universities and university administrators to assume a special sense of duty to both protect the institution and to protect those who study within the traditional academy."

She goes on to explain "the unusual sense of obligation to students" because they are legally adults but "treated more like children." She calls this "a quasi-parental ambivalence."

What's truly unusual is Poff's choice of words because social workers, including the professors in UNBC's school of social work, have a precise word for parental ambivalence: neglect. That may be a harsh conclusion to glean from Poff's dated article. At best, however, she's describing a scenario where professors set the terms of their one-way relationship with individual students, deciding unilaterally how, when and where they will exercise their parental authority.

In the modern context, it's not just journalists but students who bristle at this academic condescension from the professoriate. The University of Kentucky is currently suing its student newspaper after the newspaper published leaked documents regarding specific claims made against a professor accused of groping students. The school investigated the matter and the professor left the institution but few details were made public until the newspaper uncovered the story. Now the university is arguing the newspaper had no right to publish private records.

As a recent New York Times story shows, there are several other similar cases going on at the University of Kentucky and Indiana University. The student paper at the University of North Carolina-Chapel has taken the opposite tact, suing the school for refusing to release details on campus sexual assault cases.

Back in 2003, Poff wrote about the four "ideal characteristics" of a professor: calling, competence, character and courage. Sadly, she didn't note that these are ideal characteristics for post-secondary students and for working journalists, as well. She implores professors "to advocate the truth even with the truth is neither popular nor expedient in terms of one's own well-being."

That is exactly why The Citizen sought to publish UNBC's task force report on sexual assaults.

Poff also describes the ideal university as "a safe haven for the articulation of all ideas... and the safeguard of intellectual autonomy."

UNBC does not hold a monopoly on pursuing that ideal, nor do its professors. The Citizen aspires to it every day, as do other local news outlets, as do the student journalists at UNBC's student newspaper, Over The Edge.

Sorkomova's death was a tragedy, not just for UNBC and its leaders, but for the whole community.

Looking back 17 years, however, there are still lessons to be learned, starting with the value of transparency and public accountability.