Measles outbreaks are occurring in the U.S., Ontario, Quebec, and the Lower Mainland. While we haven’t yet seen any local cases of measles, we know from the pandemic how quickly that can change.

The COVID vaccine hesitancy that we saw during the pandemic has been spreading to other vaccines. This has led to the resurgence of measles, something we thought we’d beaten decades ago. It is a painful reminder that even in a post-pandemic world, we’re still vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases.

The antivax sentiment we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic is a major factor in this growing threat. Misinformation about vaccines has made many question their safety and effectiveness, despite over half a century of use and overwhelming scientific evidence that vaccines work.

However, vaccination rates, particularly among our younger populations, remain dangerously low. That rate use to be in 93 to 95 per cent range, now just 82 per cent of two-year-olds in BC have received their first dose of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, according to the province, and only 72 per cent of seven-year-olds are fully vaccinated. These gaps leave a large portion of the population at risk.

This is not a hypothetical concern. In places like Gaines County, Texas, a measles outbreak led to the deaths of one child and one adult, even though the vaccination rate there was 82 per cent — a familiar number.

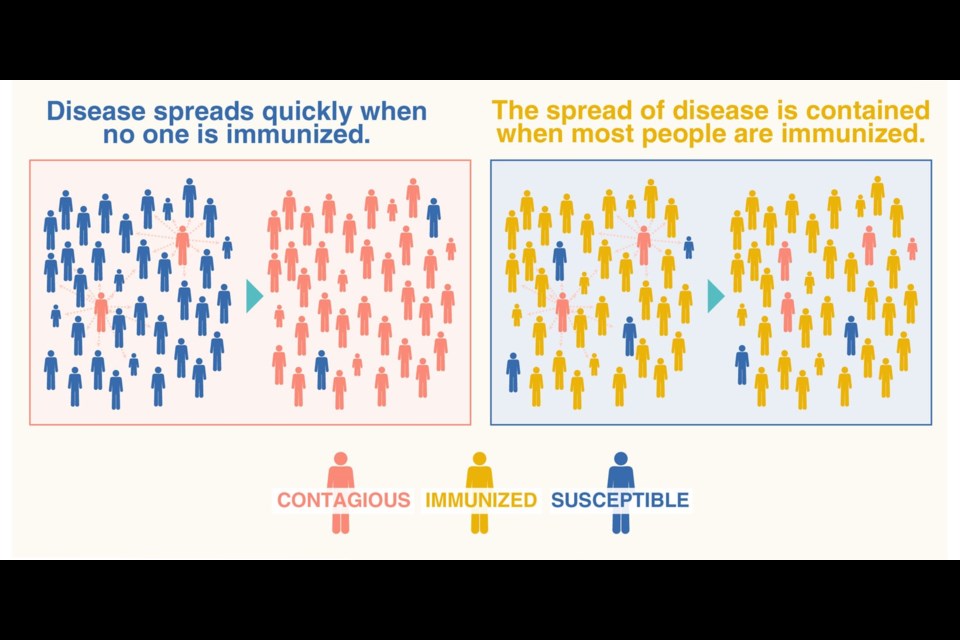

When vaccination rates fall below 95 per cent, the risk of outbreaks increases dramatically.

BC’s rates are even lower in certain areas, like the Northwest and Kootenay Boundary, where only 74 per cent and 62 per cent of children are vaccinated, respectively. This puts our communities at direct risk of an outbreak.

Measles is really, really contagious. One infected person can contaminate the air in a room for up to two hours, letting the virus spread rapidly among unvaccinated people in that room, and then on to the people they later encounter, and so on, exponentially.

It isn’t just about a rash. Getting measles can mean severe complications, including brain swelling and deafness and even death. Measles also weakens the immune system, leaving individuals more vulnerable to other illnesses. There is no treatment or cure for measles.

And it can be fatal. That’s right. One in every 1,000 people who contracts measles will die.

We can avoid this through vaccination. But there are still people who would put their own vaccination theories (or fears, or suspicions) ahead of their community’s health and their children’s.

Experts have highlighted how even small gaps in vaccination can lead to outbreaks, putting everyone in danger.

When vaccination rates are low, large numbers of people, especially kids, are susceptible to infection. This puts a strain on our healthcare system and leads to unnecessary suffering, all of which can be avoided.

The solution to this problem is clear: we must refocus our efforts on increasing vaccination rates.

Dr. Jia Hu of the BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) has urged individuals to check their immunization status and make sure they’re up to date. Vaccines are free for all ages, but it’s up to families and individuals to take responsibility and ensure they are protected.

Another point: Parents have to take care of making sure their kids’ immunizations up to date. The pandemic disrupted many children’s vaccine timelines, and now is the time to catch up.

For measles, two doses of the MMR vaccine offer up to 100 per cent protection. For those who cannot be vaccinated, such as pregnant individuals or those with weakened immune systems, herd immunity is critical.

By vaccinating, we’re not just protecting ourselves; We’re protecting our community, including those who cannot get vaccinated.

As we learned from the pandemic, our actions affect others. We must rise to the challenge of ensuring our vaccination rates are high enough to prevent outbreaks of preventable diseases like measles.

The time to act is now, before there is a measles outbreak in Prince George.

Have your say with a letter to the editor: [email protected].