The period of mourning after the death of Queen Elizabeth II was unprecedented. In my experience, the passing of an older person is followed by a celebration of life, where people gather to pay their respects and honour the positive legacy of a person who touched their lives.

The legacy of the Queen was her strong, firm guidance as the British Royal Family became international television personalities and the British Empire transitioned into the British Commonwealth.

Perhaps mourning is the appropriate term in this instance, however. The death of Elizabeth has exposed the deep wounds and polarizing views that lay just below the surface during her lifetime. Those who support the monarchy have been front and centre since September 8, and those of us who see the contradiction that this institution exposes have been either shamed, silent, or arrested.

While history books once were written only by the victor, today we are aware of the crimes against humanity and even genocide that have been committed in the name of the British King or Queen. We also know that committing these crimes enriched the coffers of said royalty and their noble cronies.

This is not to say that the Crown only did terrible things. The Royal Proclamation of 1763, for example, recognized Indigenous land rights in North America. It also demonstrated that the British were capable of arranging mutually beneficial agreements with other nations, with British companies getting furs and Indigenous people getting products that were useful to them. The problem was that by the early 1800s, the British and then Canadian governments no longer wanted Indigenous people to have exclusive rights to these lands and had to find ways to manipulate control. How fortunate for them that they made and enforced the laws.

I also understand that for many people, the Crown symbolizes what it means to be British, and is central to the identity of royalists all over the former Empire. However, we cannot deny the anger expressed from the Indian subcontinent to the Caribbean, from Africa to Oceania, from the Middle East to North America. The British Empire enslaved human beings, destroyed functioning states, destroyed economies, and imprisoned and killed countless people.

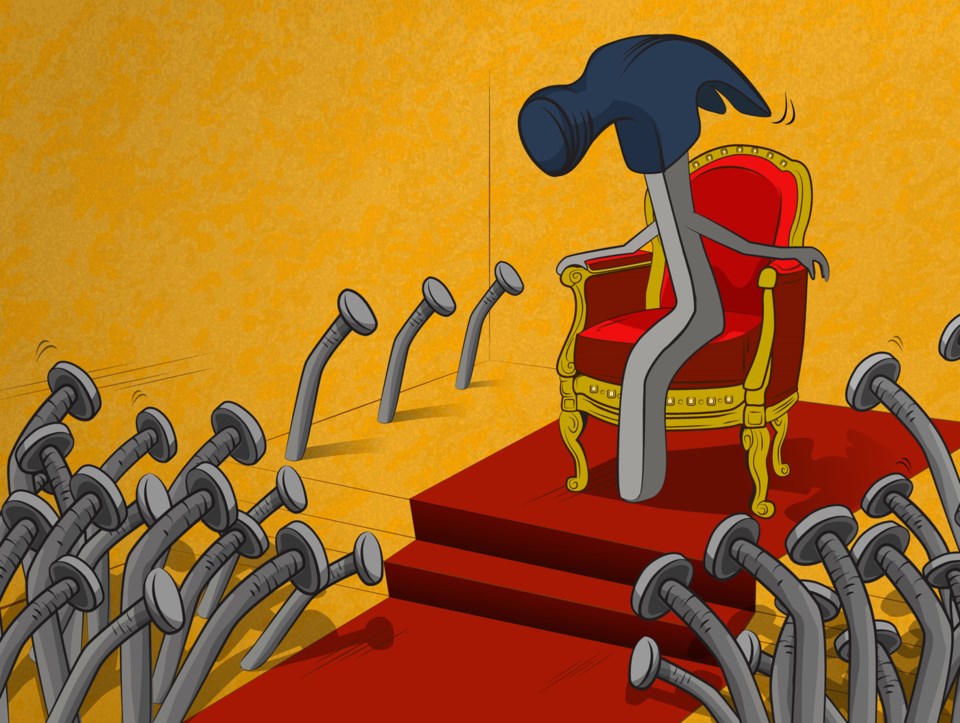

Elizabeth II had the personality and the poise to navigate the cesspool of reality. King Charles III, however, is even looked upon suspiciously by many fans of the Royal Family for his failure to recognize that the kingly tradition of clandestine affairs would not go unnoticed in the age of mass media. His statement last year in Barbados that slavery was an “appalling atrocity” was met with, “Tell us something we didn’t know,” justifiable anger, and questions of reparations from descendants of this crime against humanity.

The current British Royal Family did not commit any of these crimes and other European countries also committed genocidal acts. The current Belgian king, for example, sits in a palace built on the blood of millions of Congolese. The problem for the British Royal Family is that they also benefit from the ill-gotten wealth of their ancestors, and they are by far the most visible symbols of royalty, aristocracy, and privilege.

We live in a much more honest world than the one Elizabeth II inherited in 1952. We recognize that everyone is equal, regardless of the family they are born into. We no longer give unquestioning loyalty to individuals just because of the titles they hold. We also recognize the damage caused by slavery, racism, colonialism, and the unjust distribution of wealth.

Does Charles III or even his heir have the skills needed for the 21st century? Whether fair or not, the future of the British Crown will be determined by their ability to navigate the current reality.

Gerry Chidiac is a Prince George writer.