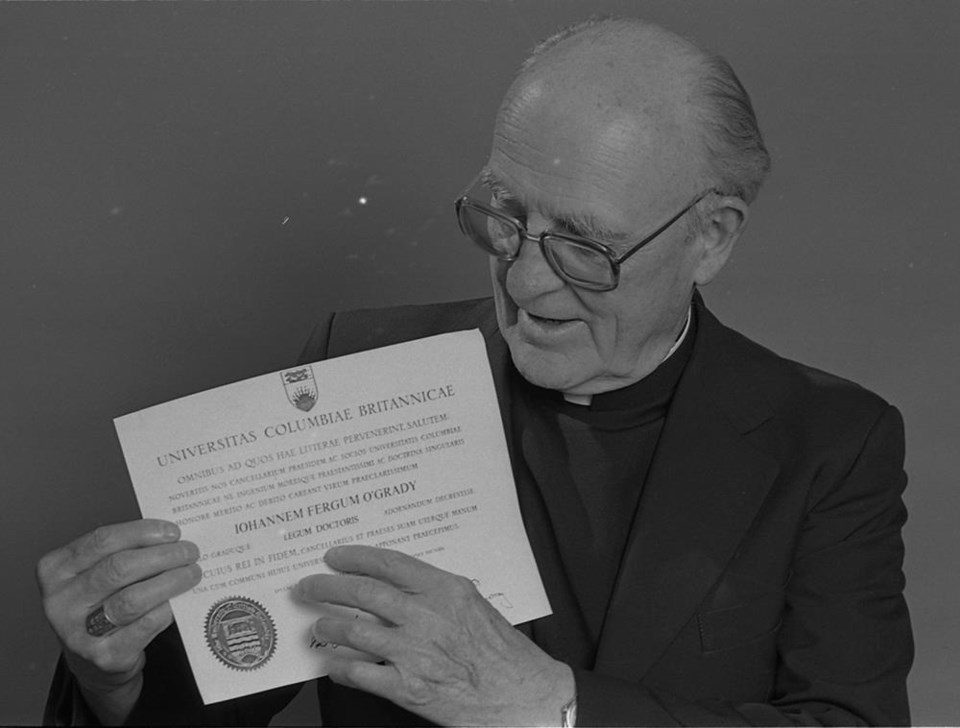

I wrote my M.A. thesis at UBC in 2001 about Bishop John Fergus O’Grady, OMI, and the history of Prince George College. As my thesis has become the sole piece of research ever conducted on this man and this school for scholarly submission, I have been referenced a great deal over the past month by local political and academic authorities.

As a student and teacher of history, I’m challenged with looking at sources and using the tools of my trade to better understand the past. Inference and empathy are two key tools used by the historian. In my own classroom, I try to teach students how to infer “truth” from a variety of sources, but to be humble in claiming to ever arrive at a “complete” truth without having considered all the available sources.

This makes history an incomplete art and open to interpretation and subject to bias. It does not make the writing and telling of history any less valuable or important, but we know that our understanding of the past is constantly changing as we face new evidence and try better to understand.

Likewise, empathy is an important consideration as it challenges us in both literature and history to consider the time, place, and context of the past in order to say something intelligent and reliable. Making use of an “educated imagination” allows the historian to begin to understand why people in the past said and did what they did.

The distinguished English historian, G.M. Young, was fond of saying that in order to understand a figure from the past, a good question to ask is, “What was going on in the world when he was twenty?” It follows that these two tools - inference and empathy - can help me understand, for example, who was Francis of Assisi as he lived in medieval Italy in his own time and place and how his sense of faith inspired him to challenge some prevailing notions of piety and justice; or why did Henry VIII do what he did and say what he said in the sixteenth century that lead to so much political and religious division.

Likewise, when a character such as Hitler is rightly vilified today it is because even in the context of the 1930s and 1940s his vitriol and murderous anti-Semitism were considered abhorrent and evil. On a personal level, it might help me better understand my own seventeenth century French ancestors who left France and came to Acadia amidst relative poverty and with courage from their sense of faith in a Christian worldview; or it could provide me some clues to help me empathize with my sixteenth or seventeenth century Illocano ancestors in the northern Philippines who became Catholics under Spanish imperialism - for better and for worse.

It might also help me as an historian to better understand the life of Fergus O’Grady, son of Irish immigrant ancestors living in a very Protestant Ontario, ordained a priest after the First World War, administrator in several residential schools in British Columbia during the Great Depression and World War Two, and then the first Roman Catholic bishop of Prince George in the least Catholic and least religious province, decidedly English and Protestant in cultural and political leadership.

Despite the challenges of his time and place, I have argued, he managed to secure financial resources and thousands of young European volunteers to build and staff schools and hospitals in a province that - at the time - did not give any funding to denominational schools be they Christian, Muslim, or Sikh.

The tools of the historian tell me that I have to understand this man within the context of his time and place. If I borrow the premise of G.M. Young, then I must try to understand the world of O’Grady’s twentieth birthday. He was born in 1908. As it is, 1928 or 1929 are two of the most tumultuous and momentous years of the century. The Great Depression ushered in twenty years of extreme government parsimony. The Great War was still a fresh memory in the minds of most in Canada and the world. The rise of European totalitarianism was met by strengthening both socialism and Communism across Europe. And let’s be clear: the assumption that European and western civilization, including religion, were superior to Indigenous, Asian, or African worldviews was not really challenged at the political level until after 1945 at best and would continue into the 1950s and 1960s. Canadian leadership was unapologetically white, Christian, and male.

As my thesis suggested, O’Grady was born into and spent most of his life within this cultural context. It follows that to judge him today with the moral, cultural, and political lens of 2021 is unfair, ignorant, and clearly ahistorical.

I will not even pretend to speak from the perspectives of an indigenous political leader, a CBC journalist, a local museum curator, a member of the UBC honourary doctorate committee or the mayor of Prince George. You each have your own tools for understanding the past and trying to tell your own story and with your own agenda.

In my own research and lived experience, however, the tools of inference and empathy - the contributions of the historian - tell me that O’Grady is not the villain he has been made out to be. In his own context of time and place, he was shrewd, progressive, and compassionate. There is no evidence he was a genocidal maniac, a murderer, or someone who spoke about his religion or Indigenous people so entirely different from other men in positions of leadership at the time. My thesis showed him to be a man who spoke as men spoke in the first half of the twentieth century. He can’t be expected to speak from any other context.

If he was racist, misogynistic, hateful, and evil within his milieu - just as we would say Hitler was clearly racist, misogynistic, hateful, and evil in his own milieu - then fair enough, tar and feather him, rip down his name from every signpost in the city. I don’t ever want to see a Hitler Boulevard in Prince George! But I would challenge any historian to find a journalist, curator, mayor, or businessman who spoke with any more enlightenment or sophistication during the Great Depression or shortly after the Second World War.

O’Grady did as much as anyone else at the time to fulfil the dreams of integration in Canadian classrooms in the 1960s and 1970s. He was ahead of his time in church history as he advanced the role of lay people in positions of church leadership and education. He petitioned Ottawa to allow Indigenous families in northern BC to at least have the choice to send their children to Prince George College - the only Catholic high school in northern BC. From 1960 to 1990, literally thousands of Indigenous youth attended this school entirely voluntarily.

Finally, my own sense of history shows me that too often in recent history attempts to right the wrongs of the past, though good intentioned, merely sow the seeds of future conflict and pain. We need only look at the Middle East and parts of central and southern Africa for clear antecedents. Let all of us - journalists, curators, mayors, and historians - attack vigorously and with honesty and outrage the sins of the past, the misdeeds, the injustice, as well as the pain and the suffering inflicted on many who claimed this land as their own before the arrival of European culture and religion.

The historical “truth”, however, can’t be told if we are sloppy and ahistorical with the past.