Hadiksm Gaax di waayu, Jessie King di waayu. My name is Jessie King. I am Gitxaała, people of the open sea and Git Lax M’oon, people of the saltwater. My wil’naat’al (matriline) is traced to Lach Klan, also known as Kitkatla, approximately 60 km south of Prince Rupert. For transparency, I am also Scottish and Irish from my father. I position myself to give you context.

In August, I have seen two letters to the editor posted in the Citizen about the successes and achievements of John Fergus O’Grady. I see you and I hear you, though you are forgetting to see the forest for the trees. Perhaps a little bit of history over tea?

Indian Residential Schools, I prefer to use institutions as these were not schools by my definition, were designed with one intention.

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone. . . . Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question” (Duncan Campbell Scott, 1920 in the National Archives of Canada).

I cannot believe that in 2023, I must write this again, that Indigenous peoples have to educate people on this once again. That these editorials are published one month before National Truth and Reconciliation Day is both traumatic for me and tragic for efforts towards reconciliation. I am tired; I am not yet 40 and I am tired. Tired and heartbroken, but I remain hopeful that my children will not have to continue these conversations when I become their ancestor.

These are parts of the letters to the editor I am addressing:

“I truly believe O’Grady was a great man who loved all people and mostly loved the First Nations.” (PG Citizen letter to the editor, August 28th, 2023

“A young Indigenous woman who became a friend of mine, from the Williams Lake area, attended the high school named Prince George College since the public schools at that time did not accept Indigenous students. She then went on to become one of the first Indigenous registered nurses in B.C.” (PG Citizen letter to the editor, August 30th, 2023)

What is the problem in defending someone that did a few good things while playing a key role in the assimilation agenda of colonial Canada?

Everything.

Please, spare me the anecdotes of a few good examples and let us really take a look at what this commentary aims to do.

First, I do not disagree with your viewpoints; sure, maybe you did have great interactions with this person. This is an example of how you can see more than one perspective at a time, this is called two-eyed seeing (termed by Mi’kmaw Elders Albert and Murdeana Marshall). I am not diminishing your experiences by clapping back by saying you are wrong.

I am saying, however, that you have chosen to trivialize colonial history by highlighting a few good deeds by one person. A few good examples does not absolve someone of their efforts to maintain institutions that were specifically designed by Canadian officials to eliminate family in my grandmother’s generation. Please do not trivialize this desert-sized violent colonial agenda by focusing solely on your grain of sand.

The Canadian government sent observers to the U.S. to study their Indian Boarding schools. U.S. Indian Boarding schools were designed to rid them of Native Americans, to control them, to remove them, and to relegate them to lands away from Americans. Yes, the prime minister at the time, John A. MacDonald, sent Nicholas Davin to report on the civilization of Native Americans to justify public funding to do the same in Canada. Here is an excerpt from Davin’s report submitted in 1879:

“The missionaries’ experience is only surpassed by their patient heroism, and their testimony, like that of the school teachers, like that of the authorities at Washington is, that if anything is to be done with the Indian, we must catch him very young. The children must be kept constantly within the circle of civilized conditions” (Davin, 1879, p. 24)

The key to accomplishing assimilation was to catch us while we were young and finding people willing to imprison us at these institutions, people who often were not trained to educate in poorly funded institutions. Children were physically, emotionally, and sexually abused if not killed in horrendous ways. Your examples of a few good deeds attempts to dismantle those truths. It gives people permission to look away from the unmarked graves being found on the sites these institutions ran on and it allows us to be complicit because it is comfortable.

Disguising complaints about streets being renamed in 2023 by sharing a few good examples of someone who played an active role in maintaining institutions to disappear my ancestors, me, and my children is nothing but an attempt to undo the work many good people are doing towards reconciliation. Histories need to tell both sides of a story that until now have largely been written from a non-Indigenous perspective. In addition, these efforts spit in the face of the work many of us are doing now as adults to reclaim cultures, languages, and belonging that was stolen from our parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents.

Despite this, my grandmothers would ask me to be gentle and I tend to agree. I encourage you to keep learning; do not lose your good examples of this person, but do not do it at the cost of erasing the harms that same person committed.

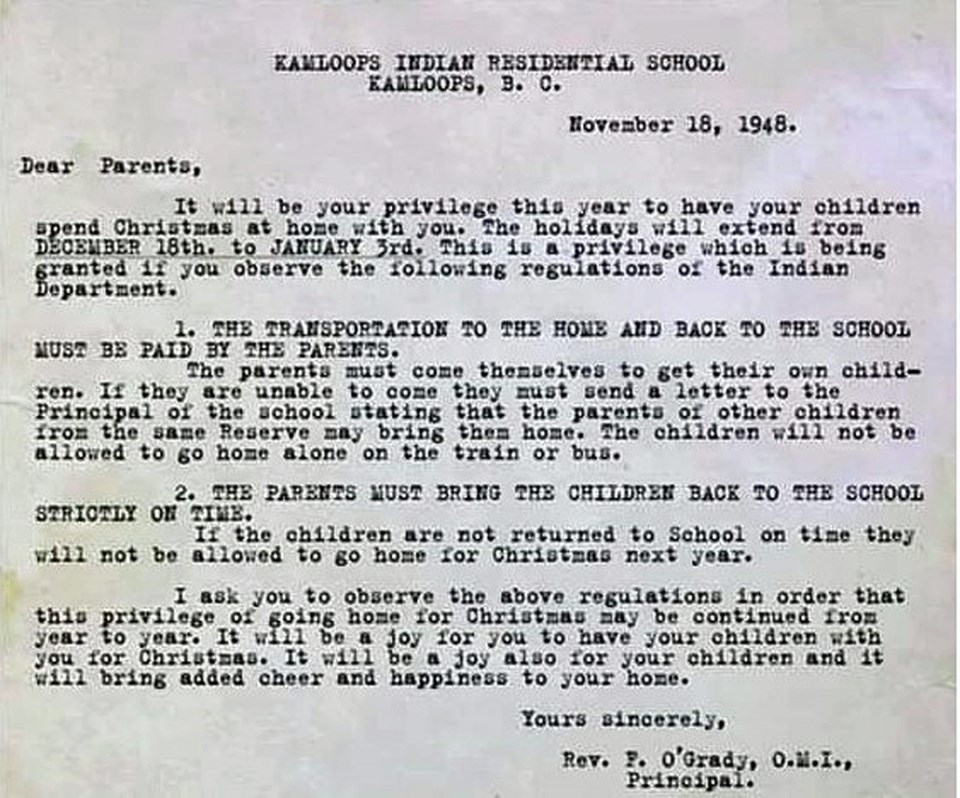

The very same person wrote the letter above to parents of children attending Indian residential institutions indicating how much of a privilege it would be to have their children home for Christmas if they followed Indian Department regulations. These are the historical harms people continue to heal from in contemporary spaces and will continue to do so with or without your empathy and compassion if you choose to remain complicit in your own version of history.

To my Indigenous brothers, sisters, and non-Indigenous allies working towards seeing the full picture of our shared history, I see you. Now we can keep going.

Jessie King

Prince George