Doug Leslie will be remembered for the way he made strangers feel like instant friends.

I got to know him briefly one summer when my family rented the house next to the lake house he built with his own hands on the southeastern shore of Fraser Lake near Beaumont Provincial Park. We hadn’t been there more than a few minutes when the kids next door wandered over to meet our kids, and before long, we were introduced to Doug and his wife at the time, Donna.

They all made us feel like long-lost cousins and went out of their way that entire week to make sure we had a good time.

“He was everybody’s best friend, he gave the best hugs,” said Megan Leslie, his 27-year-old daughter. “We would go out with him as kids, and he would spend hours talking to everybody wherever we’d go. He didn’t have many close friends, but everybody loved him.”

Doug died March 15 at age 71, almost a year after he was diagnosed with lung cancer. His death comes 14 ½ years after his 15-year-old daughter Loren was murdered by Cody Legebokoff.

Her body was discovered Nov. 27, 2010, off a logging road along Highway 27 north of Vanderhoof by a conservation officer investigating after the RCMP had pulled over Legebokoff, who had told police he had killed a deer.

One of the youngest mass murderers in Canada, Legebokoff was 24 in September 2014 when he was convicted of four counts of first-degree murder in the deaths of Loren, Natasha Montgomery, 23; Cynthia Maas, 35; and Jill Stuchenko, 35. He was sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years.

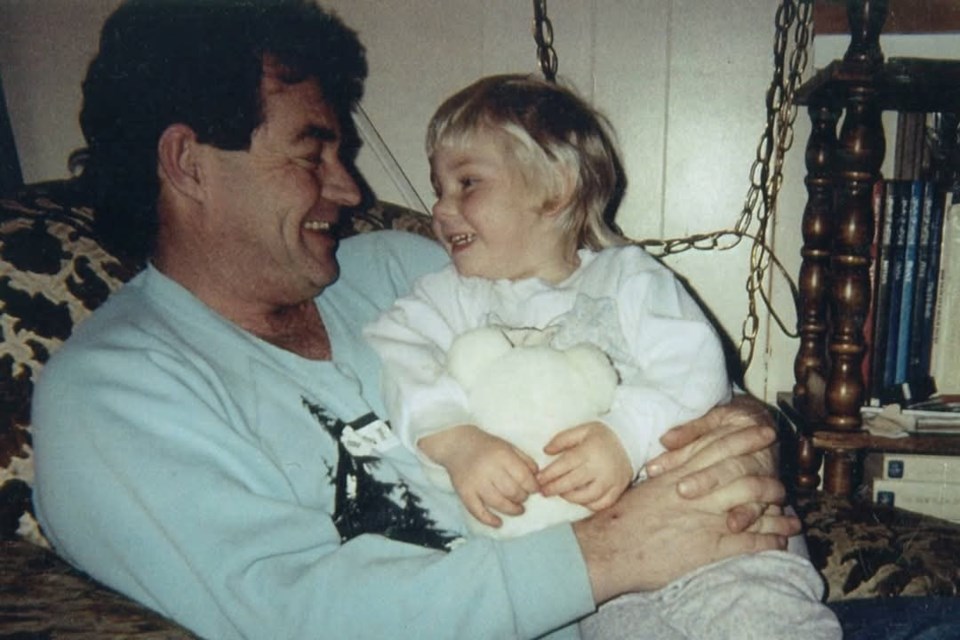

Doug had three children — Robert, Loren, and Megan — and a stepson, Ricky, from Donna. He and Donna separated before Loren’s death. Loren was living with her mom and siblings in Vanderhoof at the time she was killed.

After she died, Doug made it his mission to tell everybody about the goodness his daughter brought to the world.

“People have to start caring for each other the way she cared for others,” he told Citizen reporter Bernice Trick a few weeks after Loren’s death. “She lived in such a positive style. It's so easy to live your life like that, and yet lose it.”

From a young age, Loren had only partial vision in one eye and was legally blind. She made up for that with her listening skills. She stood up to bullies and wasn’t afraid to help anybody defend themselves against injustices, and Doug used his daughter’s compassionate words to inspire others to find that courage. It awakened something in himself he had in common with Loren.

“I know who I am,” Loren wrote. “I don’t need to hurt others to build myself up. But I do hear well. I hear others cutting their friends apart, saying unkind things, just to make themselves feel better. I hear people’s feelings being hurt by those ignoring them. I hear when no one speaks to me because I choose to be more considerate of others, and not follow the crowd.

“I hear tears on people’s faces who aren’t accepted because they don’t have the right look, the right clothes, or they aren’t cool enough to be popular. I hear the loneliness of people sitting in folding chairs at dances because they’re not loud enough to be heard... But I hear them.”

After Loren’s death, Doug formed the Loren Donn Leslie Foundation to promote youth empowerment. The charity organized fundraising walks and other events to support student bursaries and build projects like the commemorative park benches installed at schools in Fraser Lake and Vanderhoof, which serve as a reminder to students of the need to take care of one another and speak out against bullying.

Doug provided support to the family of Greg Matters, a Canadian soldier shot and killed by the RCMP in a 30-hour standoff at his home east of Prince George in September 2012.

He participated in the federal government’s National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and went out of his way to take part in the protests.

“I thought it was really cool that he put himself out there like that,” said Megan. “I know when I was in high school, he did a lot of marches for them and spoke at a lot of rallies to get involved.

“Part of what I didn’t appreciate at the time was that he did drag me around to all these things, and I kind of felt the only time I was with him was when he pulled me out of school to go to these rallies. But it was important.”

For seven years, Doug wrote a daily blog addressed to Loren. It was his way of grieving and venting the emotions he felt for her. He had planned to write a book about how he coped with his loss to help other parents deal with their own personal tragedies of losing children. After his death, the family received several messages from people who told how Doug had helped them get through those terrible times.

“He ended up getting really close with a couple of family members of (murder victim) Jill Stuchenko, and they are some of my biggest supporters to this day just because of how much they loved my dad,” said Megan.

Doug quit school at Nechako Valley Secondary when he was 16 to join the workforce as a logging truck driver. He also worked as a heavy equipment operator at Endako mine until it closed in July 2015. He returned to logging for Corjan Contracting and was still working until cancer took over his life.

“He was a great mechanic, a great driver, and a great guy,” said Megan. “His cars, his house, his kids, and his relationships were kind of everything to him. He was genuine, lively, and stubborn. He was all about how you make people feel and not about your material belongings. For him, it was all about having time to make somebody smile or being like a friend. I think that showed in pretty much everything he did.

“He had this acute understanding that he never got a lot of what he wanted out of life, I’m sure. He was super selfless and hardworking. If you chose any day in his life, you could see he sacrificed so much to be able to be there for the people he loved.”

Doug had a 1953 Buick and was active in the Fraser Lake Car Club. Megan said her mom found the receipt from the day he bought that car, which showed he wasn’t there on the day Megan was born.

“That car was supposed to connect us because it was made the year he was born, 1953, and then he bought it the day I was born,” said Megan. “He lost it for a while but bought it back and tried to give it to me (a few years before he died), but he had a faster one, so I took the faster one instead. I got a 1967 Buick Riviera. That was always the plan after he was gone, to give them to us.”

Megan admitted she wasn’t that close to her dad until later in his life. When she was young, she resented the extra time and attention he gave to Loren, and it wasn’t until just before his cancer diagnosis, when they went together for the first time to visit Loren’s gravesite, that she understood he gravitated to Loren because he felt she was vulnerable with her vision deficiencies.

“I used to wonder why my dad spent so much more time with Loren,” said Megan. “We had a conversation, and he apologized for becoming obsessed with her death, writing to her two or three times a day on Facebook, and he wouldn’t check on me at all.”

“He acknowledged it before he passed, and that brought us closer. I wasn’t supposed to know. No parent wants to admit that they have a favourite child. There’s just no good way to grieve in that kind of situation.”

Loren was two years older than Megan, and they were best friends throughout their lives. She remembers her as a bit of a rebel who changed hairstyles often, depending on her mood.

“She was such a different kind of being, and kind of like my dad, she could make friends with everyone,” said Megan. “Everyone thought of her as their best friend except for the weird girls who bullied her at high school. In our small town, she was so true to herself at such a young age, like she was the only punk around here at that time. It wasn’t like a cool thing in a town where everybody else is a farmer. She was fully a hard-core loser in her own identity, and it was incredible.

“She didn’t have too many friends around her, and the internet was her playground. She was already getting bullied for her eyesight or getting bullied because she was a little chubby, and instead of trying to hide or fit in, she was wearing those rainbow spiky belts and just rainbow punked out. People who saw it, loved it. I still have a hard time trying to wrap my head around how she understood the things she seemed to understand.”

A celebration of Doug’s life was held Saturday, March 22, at the Nazdleh Whut’en Hall in Fraser Lake. His ashes will be buried this summer in a plot next to Loren’s at Fraser Lake Cemetery.