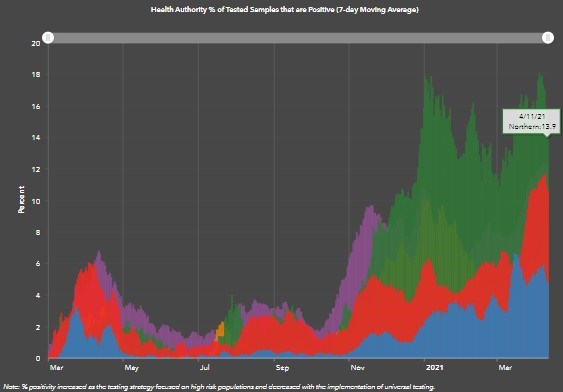

While B.C.'s COVID-19 numbers continue to rise, Northern Health's positivity rate is starting to trend downward.

According to data from the BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC), as of Sunday (April 11), Northern Health's seven-day moving average for positivity rate is at 13.9 per cent.

On April 6, the positivity rate in the region was 17.9 per cent.

Fraser Health currently sits at 12.2 per cent, Vancouver Coastal Health is at 10.6 per cent, Interior Health at 8.2 per cent and Island Health at 4.7 per cent.

The provincial positivity rate is at 11.2 per cent.

One of the biggest contributors in B.C. and high positivity rates is the P.1 variant, originating from Brazil, with officials struggling to stop transmission.

Scientists believe that P.1 can spread more easily than other strains, may cause more serious illness in some, and may be resistant to vaccines.

The path to finding P.1 cases is to run positive COVID-19 samples through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests that determine whether the cases are of variant forms of the virus, but do not specify which kinds. Scientists then conduct genome sequencing to determine specific variants.

The standard process through the first week of April was for BCCDC researchers to screen about 90 per cent of new positive COVID-19 cases with PCR tests to determine if the cases were likely variants of concern.

Researchers would then take any positive test and conduct full genome sequencing to determine the exact variant in the infection.

The process that provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry outlined on April 8 will be to do fewer full genome sequencing tests on cases that are known through PCR test results to be likely variants of concern.

"We need now to shift our strategy so that we can use the whole genome sequencing capacity we have in B.C. to do more systematic testing and sampling of all of the strains to make sure we're not missing another important one that may be arising," Henry said.

"We don't need to test so much anymore to understand if we have the [B.1.1.7] U.K. strain here, because it is here, and it's increasing, and it is causing more transmission in communities around the province."

Genome sequencing in the future will focus more on monitoring to determine whether someone has been reinfected, whether there have been what Henry called "vaccine failures," and for what she called "escape variants," which may not respond well to B.C.'s immunization program.

The result, however, is that there could be less clarity on how fast the P.1 variant in B.C. is spreading because researchers are. not likely to conduct as many genome sequencing tests to seek to find those cases.

The province recorded its first P.1 infection on March 9, after researchers detected 13 cases.

Conducting PCR tests and then genome sequencing can take many days, however, so it is likely that B.C.’s first P.1 infection happened before March 9.

Regardless, by March 16, researchers had discovered 34 confirmed P.1 cases in B.C.

By March 23, the case number had tripled to 110, and it tripled again by the next week, to 370 cases.

On April 6, B.C. had identified a total of 877 cases of P.1, or 87.7 per cent of the 1,000 P.1 cases discovered Canada-wide.

Henry started sounding the alarm about “variants of concern” in February.

Henry first acted on her P.1 concerns on March 29, when she said that a “worrisome cluster” of P.1 infections at Whistler Blackcomb had helped prompt her to shut the resort down. She allowed other ski resorts across the province to remain open.

Henry added at that press conference that not only was the P.1 variant more transmissible, but it also had “been shown in some parts of the world to be less amenable to the vaccine.”

As of this publication (April 13), Northern Health has recorded 6,567 positive tests for COVID-19, which has included 130 deaths.

There are currently 353 active cases with 27 people hospitalized across the region, including 13 in critical care or ICU.

- with files from Glen Korstrom, Business In Vancouver