A proposed $3.2 million interest-free loan to the Marriott Courtyard development is a smart way to solve a downtown eyesore, say city councillors, but the project's critics say it is a waste of downtown revitalization dollars and an unnecessary risk.

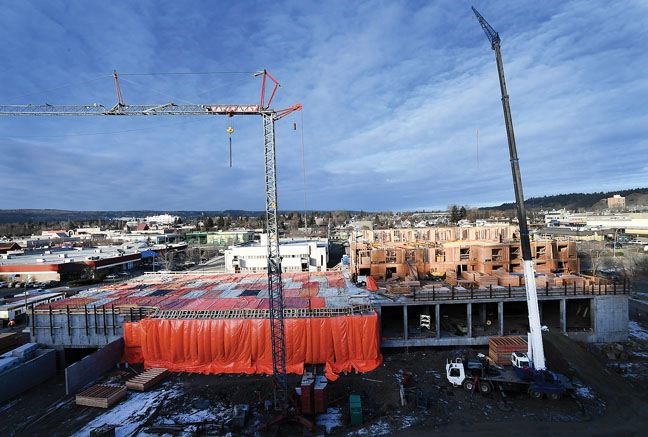

"Mayor, council and senior administration are all aligned on the steps taken to get... the bunker of concrete and rebar in the middle of our downtown to where it is now, and that's shaping into a hotel, make no mistake," said Terri McConnachie.

For more than a year the city has been working with Rod McLeod, PEG Development and Blue Diamond Capital, to start construction again on the downtown site next to the library.

In July, the $35 million project was announced. McLeod did not respond to a requests for comment.

The loan is offered through the Northern Development Initiative Trust, which set up a downtown revitalization fund of $5 million in 2011 that has since been used by six other projects.

"We don't have a whole lot of tools to attract and retain businesses," said Coun. Garth Frizzell.

"It's a pretty innovative way, but we've got to. We've got to work harder to attract, retain and improve businesses. I think this was a smart thing to do and it's paying off."

The city hoped to offer the full value of the property's improvements - an estimated $5 million - but was blocked by NDIT, which said it wouldn't top-up the fund, calling it a one-time program.

Following The Citizen's story referencing the trust's serious concern for the project, Frizzell said he's trying to wrap his head around the Marriott being a risk to the city.

"How could that be, if they're putting millions into the construction of it? The building will be there. A property taxation and in fact local government in general have the best credit rating in North America... our municipal finance authority gets the rates it does because we're guaranteed, we're the safest bet in North America."

But risk is exactly the term that some use to describe Prince George's approach to this project.

On top of the $3.2 million, the city is preparing a proposal to strike a rule on the fund preventing the city from also giving a 10-year tax exemption on the remaining value of the improvements. Both Frizzell and McConnachie said they would take a careful look at the proposal before commenting.

The Canadian Federation of Independent Business, which speaks for small business - including about 250 members in Prince George - called the approach troublesome.

"On the face of it looks like a real mess. It sure seems like a case of good intentions gone bad," said Richard Truscott, vice president of CFIB's B.C. and Alberta chapter.

"I think council's hearts are in the right place but they maybe need to give their heads a shake because this could be a very bumpy road that they're travelling in and it looks like they're continuing to travel down."

He called using the bulk of the NDIT money - 64 per cent of the $5 million fund - an "opportunity cost" that keeps that money out of the hands of other deserving businesses.

"The last thing you want to do is turn entrepreneurs into grant-preneurs who are busy chasing public dollars rather than focusing on building a solid business plan."

Since 2005, the city has offered 10-year property tax exemptions on the value of the assessed improvements to downtown buildings.

The Marriott developers can still choose this option if city council or the NDIT board rejects the pitch to offer cash from the Early Benefit fund as well as a 10-year tax exemption - or it can choose the offered $3.2 million.

But this approach - tax increment financing - gives the developer cash for the tax on the value of the improvements.

And in this case, since the loan is repayable over 10 years, it gets the full amount up front. NDIT is an essential piece because B.C. regulations don't allow municipalities to hand out loans.

The cash amounts to an interest-free loan that also doubles, in part, as a tax exemption because it's paid off through the property taxes it gives to the city.

The city then passes the relevant portion onto the trust. An added tax exemption could affect the trust's ability to recoup those funds, NDIT has warned.

Marriott won't be the only hotel that qualifies for downtown property tax exemptions. The Ramada on George Street got $115,069 in 2015 and $116,186 in 2014. Others businesses also qualified for exemptions last year, like the Bank of Nova Scotia and The Keg - both under $25,000 - and Commonwealth Health for $93,397.

Trent University economic professor emeritus Harry Kitchen said the bulk of evidence on revitalization tax exemptions show the vast majority do not lead to increased economic activity.

"If they need a tax incentive in order to survive you've gotta ask yourself if it's worth giving to them in the first place," said Kitchen, who worked as a consultant and advisor for a number of municipal, provincial and federal governments and has written extensively on local government expenditures finance, and governance in Canada.

"It may mean there isn't enough of a market to support what you're after."

That case wasn't necessarily made, but city manager Kathleen Soltis said the incentive was necessary to attract that business.

"Who knows if they really need it?" said Kitchen, who said he was surprised to see the tax exemption offered to a hotel. "I get very cynical when I hear companies saying things like that."

For Frizzell's business in 2005, buying a building downtown was made possible with the city's very first revitalization tax exemptions.

"I found that really handy," said Frizzell, who sits on the conference planning committee for the Federation of Canadian Municipalities and saw first-hand that Prince George would be rejected for key conventions because it didn't have hotel rooms nearby.

"That's just one example but it's a pretty clear cut one for me that this helps us in those cases," said Frizzell, who said the argument for revitalized tax exemptions is they encourage development because it offers a tax break only on the increase assessed value.

"The logic to it is that by encouraging that work to happen you increase all of the area around and that increases the overall taxes so by helping the one area, the downtown ... a rising tide helps all boats and a rising value in downtown increases not just the value to all the individual owners but the taxes that come into the city as well."

Soltis echoed that assessment, saying such incentives help grow the local economy and bring in business that might be deterred by the higher cost of construction in the north, for example.

"The tax base over time is going to grow as a result of projects like this where the municipality steps in to spur on economic growth."

"That's certainly the argument they all make. Does it actually happen? There's no evidence to say it does," said Kitchen. "It's awful hard to make an economic base with an artificial tool to try and attract it, because it's not very often that these things last for a long time."

University of Toronto's director of the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance said tax exemptions, and this situation, raise a number of questions: Are they an effective strategy to achieve economic development? Would the business have located there anyway? And, who pays for it?

"If an investment is going to happen anyway, do they actually need the incentive? We often don't know the answer to that," said Enid Slack, who has co-authored work with Kitchen.

There is a stronger case for offering tax exemptions under the "but-for" principle - that a business would not locate if not for the incentive. That's the case here, said Soltis.

"But how do you know that?" Slack said.

"I believe they said that, maybe they believe that. But how do we know if it's true or not? If you're giving concessions on property taxes to one group of property owners, other property taxpayers are paying for it, and is that fair?" she asked.

That last question is what Kitchen keeps coming back to, because property taxes pay for services and those services are still being used by the business that's getting a tax break.

"It's not a freebie," he said. "Somebody else is going to have to make up that shortfall and that's probably going to be the residents. The residents then are going to pay higher property taxes on their homes. There will be a few people that will benefit from it, but is that benefit to the few people worth the cost to the rest?"

While Kitchen argues tax exemptions are unwise in most cases, Truscott said they can be good if done "carefully and thoughtfully."

"Diversifying the number of projects that are receiving this sort of support would be wise because if a couple of them don't turn out it's not the end of the world," Truscott said.

Despite the back and forth between the city and trust for additional Marriott funds, Frizzell said he didn't see the conflict between the two and complemented the trust for maintaining its funds. Mayor Lyn Hall and NDIT CEO Joel McKay also said they thought the relationship was still strong.

"We've got different needs," Frizzell said, noting the scale of projects possible in Prince George is different than the requests NDIT would get from other northern communities.

But McConnachie, who believed NDIT should have approved the additional funds for the Marriott project, did not mince words.

"Flexing muscle while sitting on a pile of money that was granted in good faith from the whole dismal sale of BC Rail deal to encourage economic development in our region," she said in reference to the source of the majority of the $185 million to set up the trust. "It doesn't help taxpayers and citizens when it sits there and it's counterproductive to their very reason of existence."

She likened the steps required by the trust to request more money to pushing a concrete bunker up Connaught Hill.

"Mayor and council and administration, we're working together to take care of business for the City of Prince George and to do what we think is best and (NDIT) needs to stick to their mandate and to their activities on their side of the fence and assist us in doing our job on our side of the fence."