The Wet'suwet'en people have been fighting for decades for legal recognition of rights and title to 22,000 kilometres of unceded territory in B.C.'s Interior.

So why would some members of the Wet'suwet'en - including elected chiefs and members of one of the nation's five clans - be opposed to a landmark agreement that would acknowledge Wet'suwet'en rights and title?

"I'm not opposed to it, but it needs to be done right, and we need to know exactly where we're going to stand before and after," said Dan George, chief of Ts'il Kaz Koh (Burns Lake Band).

The problem, say the elected chiefs, is that the deal was negotiated behind closed doors by a handful of unelected hereditary chiefs, who excluded elected band councillors from negotiations, and that the agreement signed with the federal and provincial governments may further consolidate power into the hands of a few unelected chiefs, who generally inherit their titles.

Undemocratic though the traditional Wet'suwet'en house system may seem, however, it has been recognized by the courts and government as a legitimate governing and negotiating authority, although that could end up being tested in court.

George said elected band councils plan to issue band council resolutions (BCRs) denying the authority of chiefs with the Office of the Wet'suwet'en (OW) to sign the memorandum of understanding (MOU) on behalf of all 3,000 members of the Wet'swuwet'en.

"We're all going to do BCRs on a no-confidence vote in the Office of the Wet'suwet'en hereditary chiefs out of Smithers," George said.

Asked if it's possible they might also launch a legal challenge to the MOU, he said: "You bet. We're looking at all of our options."

The Wet'suwet'en are represented by 13 houses, five clans and six elected band councils. Some members of the Beaver clan are questioning the authority of the hereditary chiefs to negotiate the MOU on behalf of all Wet'suwet'en people.

"Hereditary chiefs do not have the authority to make an individual decision, and that is what is happening here," a letter from the Tsayu (Beaver) clan to the Office of the Wet'suwet'en states.

"It is the entire Wet'suwet'en membership that holds authority over the territory, not an individual society or chief. We hereby call on the OW hereditary chiefs to withdraw their premature announcement."

The letter purports to be from the Beaver clan, but it is unsigned, so it's not clear if it represents the entire clan or just a few members.

One of the wedges that has pried elected and hereditary chiefs apart has been the Coastal GasLink pipeline. All elected band councils support the project; several hereditary chiefs oppose it and have supported blockades.

After blockades across Canada in support of their opposition to the pipeline became a national crisis, Canada and B.C. rushed to the negotiating table. They came to no resolution on the Coastal GasLink pipeline, but announced a plan to recognize Wet'swuet'en title, which ultimately involves the transfer of land ownership from the Crown.

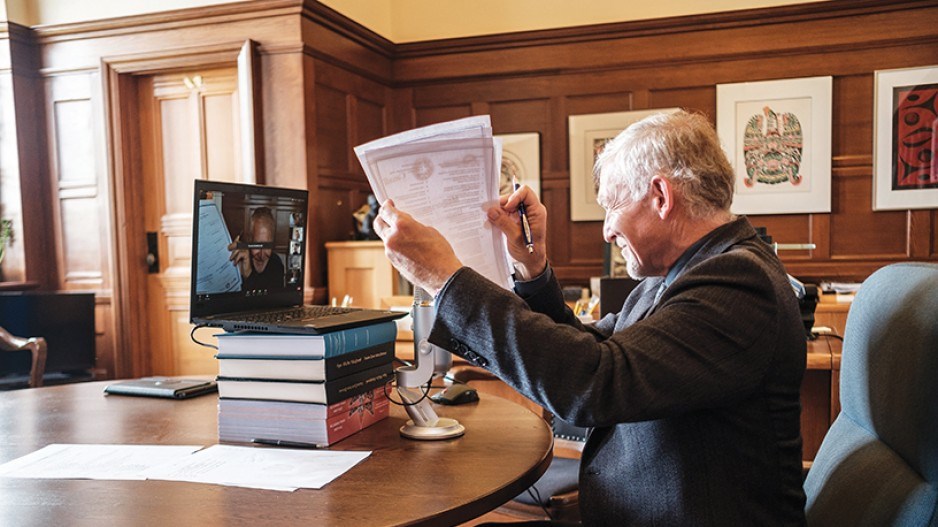

On May 14, at a virtual ceremony, federal and provincial cabinet ministers signed an MOU with the Wet'suwet'en hereditary chiefs that sets the stage for that transfer of title and governance power to the Wet'suwet'en.

"This signing of this (MOU) would be the very start of a negotiating process," said Scott Fraser, minister of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation, adding the process will involve elected chiefs, other communities, and other First Nations.

Fraser admitted that the MOU timelines - ratification before the end of this year - is ambitious, especially given the current restrictions on large gatherings due to the pandemic, which might limit attempts at public information sessions.

When the MOU was first announced in February, there was an expectation that it would be ratified by the Wet'suwet'en people in some form of community vote. That apparently never happened, in part because the COVID-19 pandemic prevented large gatherings.

As an elected chief, George has concerns over governance being concentrated in the hands of the Office of the Wet'suwet'en and hereditary chiefs.

"I've got to know where the Burns Lake band sits," he said. "Are we even going to be a band anymore, or are they just going to control everything?"

Band councils have numerous agreements signed with industry, including TC Energy (TSX:TRP), which is building the $6.6 billion Coastal GasLink pipeline through Wet'suwet'en territory.

"As elected council, we've got to know where our band sits, because we've done a lot of work for our communities for housing and economic development and everything else, so how is that going to work after this?"

Fraser said nothing changes with respect to the agreements signed by elected band councils and Coastal GasLink.

"Those agreements are done," he said. "None of that changes. This is a forward-looking document. The project's a go; the agreements are in place."

Industry in the area has similar questions.

Andy Thompson, owner of Seaton Forest Products, which has a sawmill near Moricetown, employs 22 people, most of them Wet'suwet'en or Gitxsan.

"What kind of jurisdiction are they going to have?" Thompson wonders. "That's what I'd like to know. And who is going to control the resources?"

Another question is whether provincial parks will become Wet'suwet'en title land. That has long been a contentious issue in treaty talks. A recent freedom of information filing reveals that the B.C. government is putting provincial parks and protected areas on the table as part of land claims negotiations.

Asked if parks could become Wet'suwet'en title land, Fraser didn't rule it out.

"There have been some instances where parks or pieces of parks have become part of a land selection," Fraser said.

The single biggest question for some Wet'suwet'en members is whether any elements of democracy will be included in governance. The MOU cites "clarity" on Wet'suwet'en governance as a goal.

Whatever is decided is to be ratified by the Wet'suwet'en.

But before that happens, within three months from now, the MOU commits to the "legal recognition that the Wet'suwet'en Houses are the Indigenous governing body holding the Wet'suwet'en rights and title."

So while the B.C. government offers assurances that there will be discussions on things like governance, the starting point of the MOU is to affirm that the hereditary house system is the ultimate authority.

So what if that authority decides, at the end of the day, that the hereditary chiefs will remain the sole governing body? There are fears over gerrymandering of votes.

"We've got 50% of people living off reserve," George said. "So how do you involve all Wet'suwet'en First Nations?

"It doesn't matter where they live - this is their land too. So how do you involve everybody for a vote? You can't just rely on a couple of people that show up for the meetings, and that's what they've been doing. They've been having in-house meetings and getting the vote there and saying, 'We've got quorum on our votes.' Yeah - whatever. Quorum from 20 people? That doesn't account for the rest of the 3,000 people."

In final treaty agreements, a final vote is held, giving every member of the affected First Nation a ratification vote, including members who may live outside of the province or even the country.

There is also the question of overlapping land claims by other First Nations, something that is not addressed in the MOU.

"There will be overlap issues, absolutely," said Doug McArthur, professor of public policy at Simon Fraser University. "I don't know if anything in the agreement addresses how those are going to be dealt with."