In 1918, during the Spanish flu pandemic, the Citizen was in its third year of publication. Printed on Tuesday and Fridays it was the only media outlet in the city operating at the time and an estimated 95 per cent of the 7,000 residents turned to the pages of the Citizen for their news. The following is a look back into the Citizen archives (available at www.pgnewspapers.pgpl.ca) to find out what was happening in Prince George during the year in which Spanish flu was at its most deadly.

The COVID-19 pandemic that has so far caused more than 84 million infections and 1.85 million deaths is not without precedent.

Spanish influenza infected nearly 30 per cent of the world’s population from 1918-20 and is believed to have caused the deaths of up to 50 million people, more than double the 20 million who died in the four years of the First World War. The flu clamed 55,000 Canadians and at least 77 of those deaths between October 1918 and April 1919 were people from the Prince George area.

The 1918 flu was ruthless. Patients who woke up healthy were sometimes dead before the day was over. Most of the dead ranged in age from 20-40 and most died of pneumonia, a secondary infection caused by the flu.

Prince George, with a population of about 7,000 in 1918, avoided the initial wave of infections that first appeared in eastern port cities – Quebec City, Montreal and Halifax – before the plague spread westward. By Sept. 27, when the flu was first mentioned in the Citizen, Montreal had 12 deaths and several thousand cases and it was killing 100 people every day in Naples, Italy.

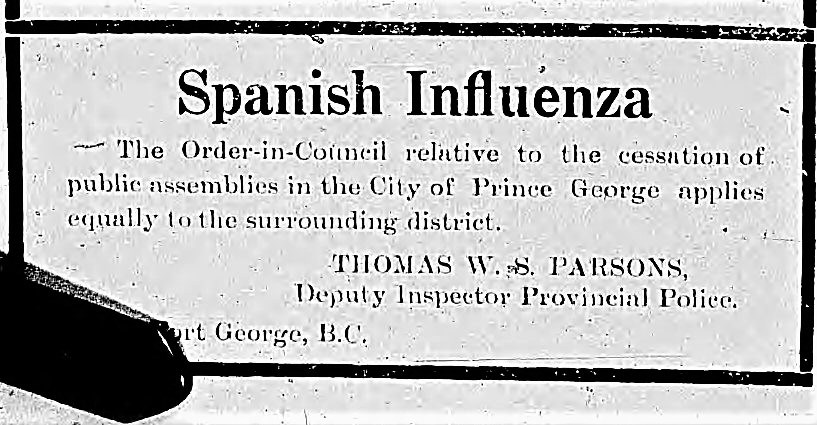

The virus mutated and during the second wave in the fall it targeted young and healthy people. Ninety per cent of the deaths in the world happened during that second wave. Deadly outbreaks in Eastern Canada prompted Prince George Mayor Harry Perry to seek provincial permission to close schools, churches, and theatres if any cases were reported in the city. By the following week, Prince George had 22 confirmed infections and on Oct. 16 local health authorities ordered all schools, poolrooms and public meeting places closed until the danger was passed. All public assemblies were forbidden.

On Oct. 17, the Connaught Hotel was turned into a temporary hospital staffed initially by volunteers and operated by the province and it opened with 15 influenza patients cared for by a nurse and an orderly. The following week, the province increased patient capacity to 60 beds with the addition of a makeshift hospital downtown at the Third Avenue Union Rooms. A few days later, the city set up a temporary emergency ward at the Millar Addition Elementary School.

The Prince George fire chief and assistant chief, as well as a majority of the local staff of the Grant Trunk Railway, were stricken with the flu. The virus spread through lumber camps east of the city and labour shortages forced some sawmills to temporarily suspend operations. Health orders shuttered non-essential businesses as they city went into a lockdown, as reported in the Oct. 18 Citizen.

“The closing of the theatres and poolrooms has left the ‘tired businessman’ without a place to spend a social evening. As a final blow to social intercourse, that democratic institution, the fire hall bears a placard. ‘For members only.’”

Prince George passengers traveling by train to Alberta were warned they had to wear masks as a precaution, by order of the provincial health authority, and that the order would be strictly enforced with nobody allowed to board a train without a mask.

Much like the advice given now by provincial health authorities to lessen the chance of COVID transmission, people were told to avoid contact with others, especially indoors, and to stay away from anyone suffering from a cold, sore throat or a cough. They were not allowed to spit in public places, told to avoid chills, sleep and work in a well-ventilated room, and keep hands clean and away from the mouth. Handkerchiefs were to be used to cover a sneeze or cough and those cloths were to be disinfected frequently by boiling or washing with soap and water.

Those who already had the flu were told to go to bed immediately under the care of a physician in a warm ventilated room for at least three days until the fever passes and to stay away from people and avoid kissing. To keep from developing pneumonia, patients were advised to remain in bed until they felt better.

In late October of 1918, infection rates were starting to decline in Prince George, as they were in most parts of the world, and it was believed the lockdown measures had worked. Some patients still suffered long after their symptoms went away and for some the longer-term effects of influenza were worse than the disease. Citizen readers were warned about that possibility when they read the Oct 25th edition.

“It is generally believed that, locally, the high point of the epidemic has passed. There remains, however, the convalescent period of the majority of those affected and this period is stated by medical authorities to be fraught with the greatest danger. The ‘after effects’ of this particular influenza have in many cases been serious and often fatal. It remains then for people to pay particular heed to the warning given by the experience of other sections and resume normal habits and exposures with care.”

During 1918-19 in Prince George, there were 64 deaths attributed to influenza, pneumonia or bronchial pneumonia. At its worst, in October 1918, the mortality rate around the city spiked to more than four deaths per 1,000 people. As of Oct. 28, there were 21 deaths in the city and all but six of the fatalities to that point were people who came in from rural areas in the region.

By Nov. 1, the city was treating 72 cases of influenza at three temporary hospitals – 25 at the Connaught Hotel, 24 at Millar School and 23 at the Union Rooms on Third Avenue. Two of the dead were the wife and 17-month-old son of J.A. Feren, the Grand Trunk Railway station agent for Prince George, who was left with five children to raise.

All railway employees were being inoculated with an anti-influenza serum by GTR physician Dr. McLean. Whatever was in that serum it was said to be “wonderfully effective” at warding off flu attacks.

In Terrace, former Prince George alderman J.R. Campbell opened a drugstore and was serving 70 influenza patients during the worst days of the pandemic. The railway gave Campbell exclusive use of a gasoline-powered speeder railcar so he could deliver drugs to his patients.

Quesnel was still firmly under the grip of the flu bug in mid-November and arrivals to the city reported there were still 40 patients being treated there at the time. By then, opinion was divided on whether the situation was actually improving. While local and provincial health authorities were convinced it was on the wane, influenza continued to ravage the surrounding First Nations communities.

On Nov. 13, Catholic priest Nicolas Coccola, a physician, returned from his medical mission in at Stoney Creek (Saik’uz First Nation) southwest of Vanderhoof and reported influenza was responsible for 43 deaths and that all of the aboriginal people on the reserve were afflicted with the disease. Most of the victims were elderly or in frail condition. By Dec. 24, 154 aboriginal people in the district out of a population of about 1,400 had died from the flu-related conditions. Many of those who survived were left in a weakened state, unable to care for themselves.

The Lhedli T’enneh community, then known as the Fort George Indian Reserve in Shelley, was hit hard and the virus killed Chief Louis Qua. Sub-chief Joseph Qua, 61, and his two children, Antoine, 37 and Virginia, 35, left the reserve to try to escape the plague and were later found dead a few miles away in a tent along the Fraser River.

Restrictions on public gatherings were officially lifted by provincial police on Nov. 15. Police didn’t enforce the order a few days earlier when on Nov, 11 armistice was declared and the First World War ended. The news from Europe was celebrated in front of two large bonfires on George Street by a crowd of people who brought out the reserves of alcohol to toast the occasion.

“There was a general uncovering of ‘flu eradicator’ in the city amid the tooting of locomotive whistles, the discords of a tin-can orchestra and the cheers of the multitude in general,” according to a Nov. 12 Citizen story.

The last temporary hospital in Prince George, at the Connaught Hotel, was closed Dec. 31. A few more flu deaths happened in 1919 in January and April but the pandemic was over.

The B.C. Provincial Police stated there were 1,800 reported cases of Spanish flu and 220 pneumonia-related deaths in the area along the rail line bordered to the east at the Alberta border at Lucerne and to the west at Kitsalas near Terrace. The actual numbers were likely higher because not all First Nations communities were included in the reports.

In December 1918, provincial police deputy inspector Parsons counted 117 deaths at Saik’uz and the indigenous communities in the Fort St. James area (Nak’azdli Whut’en, Yekooche, Tl’axt’en and Takla), with some of the reserves near Hazelton reporting nearly a quarter of their populations had been wiped out. A provincial police survey revealed mortality among all the native bands in B.C. reached 714 out of a population of 21,567.